| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A General History of the Middle East

Chapter 2: THE CHARIOT AGE, PART I

1792 to 930 B.C.

This chapter is divided into two parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| The Amorite Period | |

| Iron, the Metal of Mars | |

| The Assyrian Debut | |

| Hammurabi | |

| The "Hittites" | |

| The Hurrians | |

| The Kassites | |

| The Eleventh Plague | |

| Israel Becomes a Nation | |

| The Warrior Pharaohs | |

| Go to Page Navigator |

Part II

| The First Arabs | |

| The Middle Assyrian Empire | |

| The Aramaean Arrival | |

| The Middle Elamite Period | |

| The Other Nebuchadnezzar | |

| Suppiluliumas the Great | |

| Mursilis the Defender | |

| Tiglath-Pileser I | |

| Israel: The United Kingdom | |

| Kadesh, the Greatest Chariot Battle of All |

The Amorite Period

In Chapter 1 we depended on a document called The Sumerian King List for much of our information. The edition of the King List found at Isin treated the last event of the Sumerian era, the destruction of Ur (about 1792 B.C.), as just another dynastic change or revolution; after listing Ibbi-Sin, the last king of Ur, it said, "Ur was defeated and its kingship carried off to Isin." Well, civilization may have continued, but now it was under new (non-Sumerian) management; Isin's king, for example, was an Akkadian, not a Sumerian. And we noted that the Sumerian language passed out of everyday use before Ur fell; most Mesopotamian names after this are Semitic ones. The next two centuries are often called the Amorite period, because the Amorites were now the dominant ethnic group of the Fertile Crescent. Under them, the mixture of Sumerian, Akkadian, and Amorite cultures would produce a new culture, commonly known to us as Babylonian.

The Amorites may have come into the land between the rivers as uncouth bedouins, but they learned the ways of civilization quickly. One important change that they introduced was the system of political organization. We have described the previous Sumerian and Akkadian states as city-state empires, where one city lorded over the rest, but where government and religion remained under control of local residents except at the highest levels. The Amorites replaced this with a form of feudalism, giving or loaning out parcels of royal or temple-owned land, and by encouraging the development of private property. This created a society of big farmers, free citizens and enterprising merchants, while the temples lost some of the prestige they had enjoyed previously. As kingdoms replaced city-states, men, land, and livestock were no longer seen as the personal property of the gods, but as belonging to an earthly king. This was an important step in the development of nations and governments; for centuries to come monarchies, rather than theocracies, would be by far the most common form of government.

During this period southern Iraq was divided between two kingdoms, Isin and Larsa. At first Isin was clearly the more powerful of the two. Near the end of his reign (about 1773 B.C.), Ishbi-Erra expelled the Elamites from Ur, adding that ruined, but still prestigious city, to his realm. His grandson Iddin-Dagan (1762-1742) pushed as far north as Sippar, bringing the entire lower Euphrates under Isin's control. Isin's golden years ended in the next generation, however, when the last king of the dynasty, Lipit-Ishtar (1722-1712), was toppled in a coup. Meanwhile, a formidable Amorite warrior, Gungunum (1725-1699), became king of Larsa. In 1719 B.C. Gungunum attacked and captured Ur, using that battle to claim sovereignty over all of Sumer and Akkad. Lagash, Susa, and perhaps Uruk were taken not long after that, and now Larsa was the leader of the south.

Gungunum overthrew the ruling Elamite dynasty when he captured Susa, but after his reign a native named Eparti I recovered the capital. Modern scholars sometimes call Eparti's dynasty the Sukkalmah, due to an unusual system of succession. The Elamite government at this time did not simply pick the eldest son to follow in his father's footsteps, as was so common elsewhere, and it had three individuals, all with the title of Sukkal ("Grand Regent," Sukkalmah is plural), sharing power at the top, instead of giving all power to one. Those three were the overlord/king; the viceroy, who was usually the overlord's brother; and the prince of Susa (usually the overlord's son or nephew). The overlord and the prince of Susa always ruled from Susa, while the viceroy's headquarters was in Simashki, the royal family's home city. The viceroy was heir to the overlord, and when the position of viceroy became vacant, either because he died or because he had become the new overlord, another brother was usually picked to become the next viceroy. Not until all the brothers were dead could the prince of Susa move up to become the viceroy, and then he would name one of his sons or nephews to become the new prince. Further complicating the system was a marriage custom that called for a widow being passed on to her deceased husband's brother (the Old Testament called for this if the husband died without leaving an heir). All this may have been done to minimize struggles for the throne, because the number of legitimate candidates was extremely limited, and to give the top officials as much on-the-job training as possible. The system did break down from time to time, as you might expect, but it wasn't until after Hammurabi (see below) that sons usually succeeded their fathers to the throne. The dynasty's third king, Shirukhdukh, figures prominently in Mesopotamian records because he formed more then one alliance with the nearest kingdoms, usually to check the growing power of Babylon.

Isin never recovered from its losses at the end of the eighteenth century B.C., and the next 130 years saw ten kings, most of them usurpers. One coup that took place illustrates an unusual Mesopotamian custom that backfired. Whenever the omens were exceptionally bad, a king would place a worthless commoner on the throne as a "substitute king," in the hope that the wrath of the gods would fall on him instead. If nothing bad happened before the omens turned good again, they would sacrifice the substitute king as a thank offering to the gods, which also caused the death of the king the omens had predicted in the first place. Consequently, in 1648 B.C. king Irra-Imitti put his crown on the head of a gardener named Enlil-Bani. Yet things did not go as planned--the real king died because "he had swallowed boiling broth." (poison?) The lucky king for a day refused to step down and ruled for the next 24 years.

In northern Mesopotamia, the first dominant city was Eshnunna, about thirty miles east of modern Baghdad. At its peak, under a king named Ipiq-Adad II (about 1620 B.C.), it dominated the middle and upper Tigris valley. However, Eshnunna also had to contend with a new wave of Amorite invaders from Syria. One group occupied Mari, founding a significant kingdom there. Another tribe, led by a chief named Sumu-abum, entered Akkad in 1667 B.C. They occupied a village about ten miles from Kish which had the Akkadian name of Bab-ilani, meaning "The Gate of the Gods"; we call it by its Greek name, Babylon. Sumu-abum and his successors worked steadily to bring all of Akkad under their control, using either diplomacy or brute force, depending on the situation. A century would pass, however, before Babylon emerged as Mesopotamia's most powerful state.

Back in the south, the rulers of Isin after Enlil-Bani ruled little besides Isin itself. Meanwhile the king of Larsa died in battle with Babylon, and Kudur-Mabuk, an Elamite noble who ruled the Amorite tribes between the Tigris River and the Zagros mts., stepped in. For himself he only took the title "Father of Amurru," while he claimed Larsa's throne for his son, Warad-Sin (1608-1597). Warad-Sin was in turn succeeded by his brother Rim-Sin (1596-1536), who enjoyed the longest authenticated reign in Mesopotamian history. Remarkably, both Elamite monarchs went native (their names are Semitic, meaning "Slave of [the moon-god] Sin" and "Bull of Sin" respectively), and they tried to rule southern Mesopotamia as if they had been there all their lives, building nine temples and a dozen monuments in Ur alone. But while they may have wanted peace, they could not have it as long as Isin and Babylon remained as threats. Consequently Rim-Sin advanced northward, defeated a coalition led by Sin-muballit, the king of Babylon, and overthrew Isin in 1570 B.C. This briefly united the south; five years later Larsa gained a new opponent in Hammurabi of Babylon.

Iron, the Metal of Mars

At some point in the second millennium B.C., the Middle East saw the introduction of a metal that would change the course of history--iron. A few examples of worked iron have been found from the third millennium B.C.(1), but these were novelties, not common enough to make a difference in the technology of the day. The oldest iron tools contain significant traces of nickel and cobalt; this mixture only occurs naturally in meteorites, so for a while iron was "the metal from heaven." Because the supply of meteorites was always limited, iron was traded for as much as 40 times its weight in silver and eight times its weight in gold. Later on, it was discovered how to extract iron from red rocks dug out of the ground, or from nodules found in swamps ("bog iron"), and then the price came down to make iron competitive with copper and bronze.

Despite reduced costs, metal of any kind remained quite expensive, especially if you were a peasant. This, along with the hot weather of the Middle East/Mediterranean basin, is probably why the Parthians (see Chapter 6) were the first people on record who covered their soldiers completely in metal suits, and why Greek warriors left their arms and thighs uncovered, not to mention something more important! In pre-industrial civilizations, the typical person only owned two to five pounds of metal, which had to be divided among all the tools he needed. Weapons, especially swords, were kept light, not only to make wielding them easier, but also to reduce the cost of making them. This explains why ancient authors like Homer might take a whole paragraph to describe the throwing of a spear; the warrior was casting away a big investment, along with his weapon. In that sense, our ancestors watched a joust or a duel between armored champions with the same fascination that we have when watching a wreck in a NASCAR race; both consume a great deal of money, equipment and training. This also explains why it was a big deal, when a friend of the prophet Elisha lost an iron axe-head in the Jordan River (2 Kings 6:1-7). Only with the mass production of our own time could most people afford to live without scrounging and salvaging every last scrap of metal.

We don't know where iron was first forged in the Middle East, but Anatolia usually gets the credit, because the Hittites were the first people to use it on a large scale. By the end of the period covered by this chapter, power had shifted to the nations that learned to use iron effectively, like the Philistines. That is why the iron age is usually tagged as beginning around 900 B.C., though iron itself appeared much earlier.

The ancients had mixed feelings about iron, because the new metal was just as useful for weapons as it was for tools. In the first century A.D., the Roman scholar Pliny the Elder wrote that iron is "the best and worst instrument in human existence. We use it to split the soil, plant trees, cut vine props . . . build houses, dress stone . . . But we also use it for war, murder, brigandage." Nearly 1,400 years later, Niccolo Machiavelli agreed, when he wrote that the four most useful things in the world are men, iron, bread and money, and of those four things, men and iron are the most valuable, because with them you can get bread and money (Art of War, Book VII, para. 178). It was iron's military association that prompted the commandment in the Old Testament to make altars without the use of iron tools, because God did not want people to think of warfare when making offerings (Deuteronomy 27:5).

In the second millennium B.C., metal armor was also available, either as shields or as a suit of scales over a leather jerkin, but bronze remained the preferred material for these. Why? Because archaic iron rusted easily, and if forged more than once, it lost much of its strength, making it only suitable for things like cooking pots and belt buckles. Thus, a broken iron sword could not be repaired, and since armor was expected to take a beating in battle, it made more sense to use bronze. It took the introduction of steel and cast iron (as opposed to wrought iron), using technologies invented after 500 B.C., before smiths stopped making bronze arms and armor altogether.

The Assyrian Debut

On the Tigris, nearly 200 miles upstream from Eshnunna, there lived a vigorous Semitic people, the Assyrians. Their name comes from Assur (also spelled Ashur or Asshur), the name of their first city and their patriarchal ancestor. Over the course of the third millennium B.C. the Assyrians adopted the civilization of Mesopotamia as their own, with only minor changes. It took a long time after that, however, for them to establish a kingdom of their own; one Assyrian chronicle listed no less than 117 kings and stated that the first seventeen "lived in tents," presumably because they were nomads at the time. Each of the next twenty-one kings appears to have ruled only a city-state, meaning there were separate kings in Assur, Nineveh, Calah, Erbil (also spelled Arbela), etc.

At this stage, the Assyrians did not yet have the militarist streak that would characterize them later on. Their main interest was trade, especially with the lands to the west. The part of the Tigris valley they lived in was blessed with good rainfall, allowing both rain-watered and irrigated farms, but it was poor in other resources, especially metals, so as far back as 1700 B.C., they sent merchants to Anatolia to find what they lacked. At Kanesh (modern Kültepe, in eastern Turkey), a city belonging to the Hittites (see below), the Assyrians established a major trading colony; 16,000 clay tablets, trade records from that colony, were discovered there by archaeologists in the late nineteenth-early twentieth century. The merchants served as middlemen as well as producers; the main commodities they sold in Kanesh, for which they were paid with silver, were cloth and tin, two products that were made in other places like Babylon, and brought to Kanesh by the Assyrians.(2)

However, it was iron, not silver, that made Anatolia so attractive to the Assyrians. We noted in the previous section that iron was very expensive during this period, and to take advantage of the iron trade, the communities on the trade routes imposed taxes of up to ten percent of the goods' value. This encouraged some of the Assyrian merchants to try their luck at smuggling; we have letters from kings and other merchants warning against this practice.

Assyrian interests changed with the rise of the first or Old Assyrian Empire, founded by an aggressive king named Shamshi-Adad I (1586-1554). Unlike the previous kings, he was of Amorite ancestry, the son of a chief named Ila-kabkabu who had recently seized power in Assur. As a young man, he visited Babylon, and after his return his brother Aminu became king of Assur. With no opportunities at home, Shamshi-Adad became an outlaw, leading a group of mercenaries to take Ekallatum, a fortress which then was under control of Eshnunna; he captured it, and it served as his base for the next three years. Then Iakhdunlim, the king of Mari, was killed by his servants, so Shamshi-Adad seized that city and put his younger son, Yasmah-Adad, in charge. He left his older son, Ishme-Dagan, to mind affairs in Ekallatum, while he turned against his brother and took Assur. Once Assur was his, he rebuilt the city's largest temple, which previously had been for the Sumerian god Enlil, and rededicated it to Assur's patron deity, Ashur; henceforth Ashur would be the king of Mesopotamia's gods, from the Assyrian point of view. In subsequent campaigns Shamshi-Adad marched west through Syria and Lebanon, conquering Ebla and going all the way to the limit of the known world, the Mediterranean or "Great Sea." Thus Assyria replaced Eshnunna and Mari as the most important kingdom in northern Mesopotamia.

Shamshi-Adad did not want to rule from Ekallatum, Mari or Assur, so he chose Shubat-Enlil, a city near the source of the Khabur (a tributary of the Euphrates), as his permanent capital. The location of Shubat-Enlil was just discovered in the 1970s, and Shamshi-Adad founded several new towns nearby. Archaeologists have also discovered some very interesting letters between the king and his sons, from the archives at Mari and Kanesh. Whereas Ishme-Dagan was a chip off the old block, frequently bragging about the military expeditions he led ("At Shimanahe we fought and I have taken the entire country. Be glad!"), Yasmah-Adad proved to be lazy, irresponsible, and cowardly. In his letters to Yasmah-Adad, Shamshi-Adad lamented that he would have to supervise his son's administration forever, and remarked, "Are you a child, not a man? Have you no beard on your chin? Even now, when you have reached maturity, you have not set up a home. Who is there to look after your house?" On another occasion, when Yasmah-Adad responded to a minor raid by lighting the emergency beacon fires, thereby putting the entire country on military alert, Ishme-Dagan wrote to criticize his over-reaction: "Because you lit two fires during the night, it is possible that the whole land will be coming to your assistance."

In the end, however, Ishme-Dagan couldn't do much better at holding on to a kingdom. Upon Shamshi-Adad's death, all of the empire except Mari passed to Ishme-Dagan, and he immediately sent a letter to Yasmah-Adad, promising that the younger brother had nothing to fear as long as he was backing him up. Instead, within a few months he lost Shubat-Enlil to an Elamite invasion. Although Ishme-Dagan managed to keep his throne, he only did so as a vassal of Eshnunna (the Elamites were acting as Eshnunna's ally at this point). Two years later, Yasmah-Adad was ousted from Mari, and Zimri-Lim, a son of the late Iakhdunlim, became the last king of Mari.(3) Less than two decades after that, Hammurabi would attack and conquer all of northern Mesopotamia.

Hammurabi

When Hammurabi succeeded Sin-muballit in 1565 B.C., becoming the sixth Amorite king of Babylon, he inherited a realm eighty by twenty miles across, an area smaller than the state of Delaware. Over the course of his 42-year reign, he overcame every one of his larger, more powerful rivals, using a remarkable combination of political skills that Machiavelli would have admired; he knew when to bide his time, when to give and bend and when to strike.(4)

Hammurabi did strike more than once in his early years, but these were actions with limited objectives, not meant to destroy the opponent. In year 6 (1560 B.C.) he took Isin from Larsa, and advanced as far south as Uruk before turning back. In year 10 he campaigned east of the Tigris and captured the town of Malgum; in year 11, he pushed upstream from Sippar to take Rapiqum. Then he stayed at home for nearly twenty years, building new temples, canals and fortifications. During this time peace was kept through an alliance with Zimri-Lim of Mari and Rim-Sin of Larsa, which was opposed by another triple alliance involving the eastern states (Assyria, Elam and Eshnunna).

According to Hammurabi's own account, this peace ended when the eastern alliance, along with some Gutian tribesmen from the Zagros mts., attacked Opis, a city Babylon ruled on the Tigris, and Rim-Sin failed to send aid, souring relations between Babylon and Larsa. Then Rim-Sin began sending raiding parties into Babylonian territory, and the king of Kish, another city under Babylon's rule, learned that Rim-Sin was planning to attack him by sending 270 boats up the river to Kish. Hammurabi only hesitated long enough to say some prayers and check the omens. Some priests who had special training in this area examined the entrails of a sacrificed animal, and told him that the gods were on his side, so he and the army went forth. However, he treated his first objective, the city of Mashkan-shapir, leniently; perhaps the priests gave him some advice on strategy, too. Mashkan-shapir was Larsa's second largest city, and when he took that place without destroying it, he won over the local population, allowing him to send an army swollen with new recruits on to Larsa. Larsa itself gave up after a six-month siege, so in a single campaign, Hammurabi brought the entire south under his rule, and thus claimed to have reunited Sumer and Akkad (1536 B.C.).

The remaining states hastily put together a coalition to stop Hammurabi, but he struck first, advancing up the Euphrates in the following year against his former friend, Zimri-Lim. Mari submitted, and Hammurabi turned his attention to the Tigris, going north until he reached "the frontier of Subartu" (Assyria). Although he did not say it, this was the end of Eshnunna. However, there appears to have been a rebellion in Mari, because two years later (1533 B.C.), Babylonian troops returned, deposed Zimri-Lim and destroyed the city, leaving Mari a heap of ruins for French archeologists to discover in the early 20th century. Finally, in two separate campaigns (1530 and 1528 B.C.) he overcame Assyria, but left Ishme-Dagan in charge as a vassal. There Hammurabi stopped; predecessors like Sargon I had also conquered Elam and Syria, but those states were now stronger than they had been in Sumerian/Akkadian times, so Hammurabi settled for just Mesopotamia. He even respectfully addressed his Elamite counterpart, Siwe-Palar-Khuppak, as "Father," unusual behavior for someone who called himself the world's most important king.

Considerable information has survived about Hammurabi's peaceful pursuits. Not only was he a formidable warrior and an astute diplomat, but also a diligent, careful manager with an interest in the welfare of his subjects. 150 letters to many of his officials in the outer provinces have come down to us, showing a leader who was interested not only in tax collecting and the maintenance of the all-important irrigation system, but also minor matters like the payments of rents and petty lawsuits. The gods of Sumerian days continued to be honored, but Hammurabi made a change to encourage popular support for the state: he made Marduk, the god of Babylon, king of the entire pantheon (later they would rewrite the mythology to legitimize Marduk's new status). The only apparent failing we can find in Hammurabi's style of rule is that he did not delegate authority, but seemed to want to do everything himself; that only works as long as the man on top is competent.

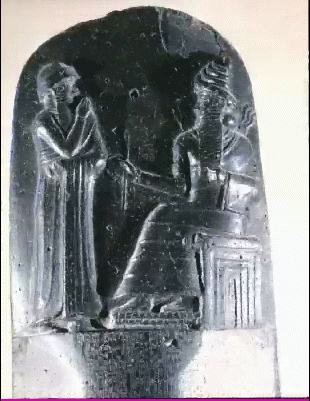

Hammurabi's most famous accomplishment is his law code, the best-preserved copy of which is engraved on a stele, or stone shaft, and now standing in the Louvre in Paris. We can no longer call it the oldest (Ur-Nammu has that claim, unless one counts the reforms of Urukagina), but it is by far the most comprehensive. After a long prologue listing the king's religious deeds, 282 laws deal with crime, trade, marriage, family and property, agriculture, the wages of workers and the fees of professionals such as doctors, and the sale of slaves. The code ends with calls for divine punishment against anyone who would deface the monument or alter "the just laws which Hammurabi, the efficient king, set up." The code was harsh by modern standards ("An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth"), with many punishments involving flogging, mutilation, and execution, but it also had many statutes designed to protect women and children from arbitrary treatment, poverty, and neglect, so Hammurabi is best regarded as a tough but fair ruler.

The top of Hammurabi's law code. Here he pays homage to the god Shamash, whom he claimed gave him the laws.

The Babylonian empire, in more ways than one, was an important episode in Middle Eastern history--and a surprisingly short-lived one. Hammurabi only lived five years after his last war ended, and because the empire had been put together by the ability of one man, it started to come undone once Hammurabi was gone. His son and heir, Samsu-iluna (1522-1485) had to put down rebellions almost immediately. Initially he was successful, but it was like mending an old piece of clothing; for every rent patched, a new one appeared. In 1515 B.C. a certain Iluma-ilu, who claimed to be a descendant of the last king of Isin, proclaimed a "second dynasty of Babylon" in southern cities like Ur, Larsa and Uruk; we know his state as the Sealand or Marsh Kingdom, because of its location along the Persian Gulf. Samsu-iluna defeated this rebellion in two or three years, but then an environmental disaster struck; the course of Euphrates river shifted to the west, leaving the cities that were once on its banks high and dry. Some scientists think that Samsu-iluna's engineers diverted the Euphrates in a new direction, using water as a weapon against the south; whether or not they did, they could not reverse the process afterwards, nor could they dig new canals long enough to get water to the southern cities. As a result, by the early fifteenth century B.C., most of the cities of ancient Sumer were abandoned; today the Euphrates flows 12 miles from Uruk, 10 miles from Ur, and 40 miles from Nippur. Nippur managed to survive because it was farther upstream than the other cities, and it could receive some water from the Tigris, but it also suffered a slump--we have records showing a wave of land sales before 1500 B.C., in which so many people sold their property and moved away that real estate prices collapsed.

Meanwhile in the northeast, an obscure Assyrian king named Adasi "ended the servitude of Assur." And if that wasn't enough, Samsu-iluna had to deal with dangerous foreigners; he defeated the Kassites, a new barbarian tribe in the Zagros mts., in his ninth year, and an Amorite army in his thirty-fifth. There was also an Elamite invasion, followed by raids from other nomads, who captured men and women and sold them back to the Mesopotamian kingdoms as slaves. Finally, a new revolt erupted in the south in his thirtieth year, restoring the Marsh Kingdom. Samsu-iluna preserved a shrunken realm for his heirs, bequeathing to them nothing more than Akkad, the land Hammurabi had started with. Four more Babylonian kings ruled over the next century. They did not try to recover the lost lands that had once belonged to Hammurabi, and newcomers like the Kassites piled up along the mountain frontiers of Mesopotamia. Soon the decline of Babylon would allow them to break in and set up their own Mesopotamian kingdoms.

The "Hittites"

The second millennium B.C. saw the theater of civilization expand into several areas beyond the Fertile Crescent. In addition, it became a more crowded place as many new peoples moved in, like the migrating Indo-European tribes, who were now spreading west into Europe and east into India. A significant innovation of their own helped; the Indo-Europeans were the first people to domesticate horses. This animal, the "ass from foreign countries," as the Sumerians called it, had been known previously, but the Sumerians never realized the advantages the horse had over their favorite beast of burden, the donkey. Interestingly enough, the horse was first trained as a draft animal; several centuries would go by before anyone learned to ride one, as opposed to having one pull wagons. By hitching a team of horses to pull a chariot, the Indo-Europeans invented a devastating new weapon that literally overturned the kingdoms of the day, including even Egypt, which was supposedly too inaccessible to invade. As chariot elites appeared alongside masses of infantry, new states emerged as well, run by those who knew how to drive the new invention.(5)

One of the new areas that became an active place for civilization was Anatolia--modern Turkey. This large peninsula, a thousand miles long from east to west and four hundred miles wide from north to south, saw many peoples pass through it, because it was on the most direct path between Asia and Europe. Appropriately, a Turkish poet once compared the land to a horse:

"This country shaped like the head of a mare,

Coming full gallop from far-off Asia,

To stretch into the Mediterranean."

Anatolia is also a place of much ethnic diversity, because it has an assortment of mountains, deserts, lakes, seacoasts, etc., which provide places for many cultures to live. Consequently, some of the folks migrating through, like the Galatians in the third century B.C. (see Chapter 6), chose to settle here. In modern times, for reasons like these, Anatolia has been seen not as a cradle of civilization, but as the crossroads of civilization. Scholars knew that this land had been an important part of the Persian, Greek, Roman, and various other empires; in fact, Turkey has more Greek ruins than Greece, and more Roman monuments than Italy. Therefore, when Anatolia appeared in history books, it was usually with outsiders in charge of it. The Bible mentioned the Hittites, and Greek authors like Homer and Herodotus mentioned the Trojans, Phrygians, Lydians, and Carians, but for a long time historians had only this literary evidence to go on; some questioned whether those peoples even existed. A few significant archaeological excavations did take place in the nineteenth century, like Heinrich Schliemann's discovery of Troy, but only after the Ottoman Empire fell in the 1920s did the Turkish government permit many archaeologists to come here. When that happened, historians gradually began to realize that this land was once a rival to Mesopotamia and Egypt, a place with many indigenous cultures, whose achievements played an important role in the shaping of civilization as we know it.

Anyway, the first inhabitants of Anatolia started building settled communities at a very early date. One of the better known ones, Catal Hüyük, was an active trading center even before 3000 B.C. Others that were founded during the neolithic and early bronze ages were Göbekli Tepe, Mersin, Alaca Hüyük, Nevali Cori, Ashikli Hüyük, Chayönü, the previously mentioned Göltepe--and Troy. Most of them showed unexpected achievements; Mersin, for example, was well protected with a thick wall, towers, and quarters for a garrison, all surrounding a courtyard where stones were kept for ammunition; this is one of the oldest fortresses ever found. But none of these communities formed a significant kingdom, and the civilizations they developed lacked some crucial elements, especially writing. The oldest written inscriptions found anywhere in this region were the previously mentioned business records at Kanesh.

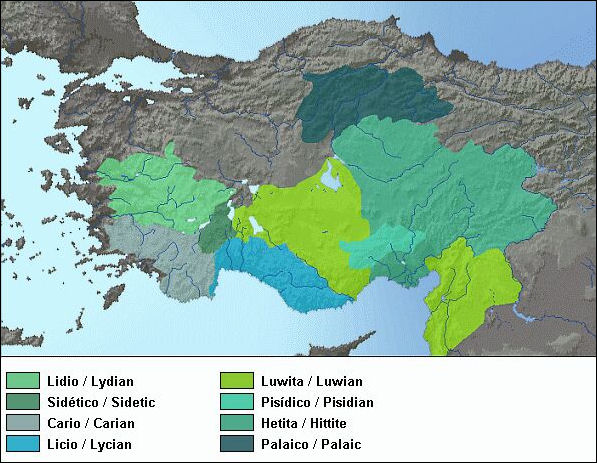

The ethnic groups we know about, that lived in Anatolia in the second millennium B.C.

Hittite characters appear more than once in the Old Testament, so it would be a surprise if archaeologists hadn't found evidence of their existence by now. To give a few examples, Abraham bought the Cave of Machpelah as a tomb for his wife Sarah from Ephron the Hittite; Esau's Hittite wives made the life of his mother Rebecca miserable; Uriah, one of King David's officers, was a Hittite. Finally, in 2 Kings 6 & 7, the city of Samaria is besieged and on the point of capitulating, when the attacking Syrians suddenly run away, after hearing what they think are the Egyptians and the Hittites coming to the rescue. However, aside from being listed with the Canaanite tribes, nothing in these stories suggests that the home of the Hittites was in the Holy Land; Jerusalem is listed as the city of the Jebusites, for instance, but no city is associated with the Hittites. Therefore, when archaeologists found Akkadian-language clay tablets that mentioned a country called "Hatti" in northern Syria and the nearest part of Anatolia, they jumped to the conclusion that this must be the land of the Biblical Hittites. Then it turned out that Hatti's capital was at Hattusas (modern Boghazköy), a site about 90 miles east of Ankara in the heart of Anatolia, so these same archaeologists felt that a mystery had been solved, and since then books have described Hattusas as the capital of a "forgotten empire."

The truth of the matter is more complicated, though. Genesis 10 describes the Biblical Hittites as descendants of Ham, but when the clay tablets found at Hattusas were translated in the early twentieth century, it turned that they were written in several languages, and the most commonly used language was an Indo-European one, meaning that the people of Hatti were "Japhethites." This was thought to be the original Hittite language, until the archaeologists discovered a non-Indo-European language named "Hattili" (alternative names for the main language are Nesili or Kaneshite). By this time, however, everybody was calling the people of Hatti "Hittites," so it was too late to change the name.

My guess is that the Hattili-speaking "Hittites" of eastern Anatolia and northern Syria were the Hittites mentioned in the Bible, and that at a later date, most likely around 1500 B.C., the Nesili-speaking tribe moved in, as part of the Indo-European migration, and took over so completely that even the name of their subjects was applied to them. We have a similar parallel in American history, where people of European, African and Asian ancestry moved to the Americas and displaced the indigenous population, to the point that when you hear the word "American," you probably think of the descendants of Old World immigrants, not "Native Americans."

According to the relief sculptures they carved, the Hittites were a short, stocky people with hawklike noses; the men wore earrings and arranged their hair in pigtails so thick that their purpose may have been to protect the neck in battle. Both men and women wore tunics, shoes with Turkish-style turned-up toes, and when the weather demanded it, long robes of wool. They enjoyed an energetic, adaptable culture, with vivid art. And with their valiant warriors, iron weapons and formidable three-man chariots, they became a power that everyone else in the Middle East had to take seriously.(6)

The records of the library at Hattusas report that original Hittite capital was at Kussara, a city that has not yet been located. Two semilegendary kings are listed as ruling from there, Pitkhanas and his son Anittas. Neither one, however, was regarded as the founder of the Hittite kingdom. Presumably these kings were from the original Hittite race, not the Indo-European Nesili that were dominant later on. Pitkhanas is credited with conquering many cities, including Hattusas, and Anittas later moved his capital to one of them, Nesa (the Nesili home town?). A dagger bearing the name of Anittas, found at Kanesh, adds weight to this story. Then the Nesili seized power, and apparently they did so violently; Kanesh was destroyed by fire in the fifteenth century B.C., and never rebuilt. The Edict of Telepinus, a remarkable document written centuries later, summarizes what happened next:

"Formerly Labarnas was Great King; and then his sons, his brothers, his connections by marriage, his blood-relations and his soldiers were united. And the country was small; but wherever he marched to battle, he subdued the countries of his enemies by night. He destroyed the countries and made them powerless [?] and he made the sea their frontier. And when he returned from battle, his sons went each to every part of the country, to Tuwanuwa, to Nenassa, to Landa, to Zallara, to Parshuhanda and to Lusna, and governed the country, and the great cities were firmly in his possession [?]. Afterward Hattusilis became King . . . "

One infers from this that the first Nesili king, the one regarded as the true founder of the Hittite state, was Labarnas I; his name became a title for all future kings. Labarnas II, his son, moved the capital to Hattusas, and changed his name to Hattusilis I, "the man from Hattusas." He also looked for new lands to conquer, and expanded southwards into Cilicia and Syria, but after taking a wealthy city named Hashshu, hostile neighbors, especially the powerful Syrian city of Aleppo, prevented further success. Finally he returned home, badly wounded, where he appointed a nephew as his successor, to continue the struggle. Not long after that, the nephew plotted to depose him; one of the most remarkable and touching documents from the second millennium B.C. is a long and bitter speech, now called the Political Testament, in which Hattusilis accused the plotters, who included three of his sons, of infidelity and ingratitude.

After the conspiracy fell apart, Hattusilis exiled the nephew and bequeathed the kingdom to his grandson, Mursilis I; he was a wise choice. Mursilis first settled accounts by destroying Aleppo, succeeding where Hattusilis had failed. Then he took Carchemish and continued 500 miles down the Euphrates; when he reached Babylon he captured and plundered it (ca. 1362 B.C.). The loot he took away included the most important statues of the god Marduk and his wife Sarpanitum, though for reasons unclear to us, they were dropped off at Hana, the headquarters of the Kassites (see below), instead of being hauled all the way back to Hattusas.

This extraordinary raid ended Hammurabi's empire. Historians have trouble explaining how he did it, though cooperation with the Kassites has been suggested. Of course Mursilis could not hold a city so far away from home; soon dangerous palace intrigues forced his return. He was subsequently assassinated, and a period of civil war/disunity followed, which lasted for two centuries. We only have the names of four kings for this time; if there were more, they are lost to history. Altogether we have a sense that the Hittites were in the same situation as the Roman Empire in the third century A.D.; many short-lived rulers followed one another, each taking the throne by overthrowing his predecessor.

The age of chaos ended when Telepinus (1150 B.C.?), the consort of a previous king's daughter, seized the throne in a bloody coup. Telepinus felt what the country needed the most was a restoration of law and order, and he showed it soon after when his wife and son were murdered; he exiled the killers, rather than have them put to death. Then he worked at establishing the first constitutional monarchy. First he laid down a precise law of succession, specifying exactly who was in line for the throne and in what order. To curb the excesses of rule by monarchy, a council of nobles called the pankus was created; this body could pass judgement on the king if he tried to murder his relatives, or even put a death penalty on him if they convicted him of such a crime.

This was the oldest known society where a law code was considered more important than the head of state. The rest of the laws of Telepinus are equally interesting, because they are remarkably humane; instead of Hammurabi's eye-for-an-eye punishments, the main theme was giving compensation to the victim. Unfortunately we do not know how they worked in practice. After Telepinus, for reasons unknown, the kingdom broke into its component city-states; the next king, Tudkhaliyas I, spent his entire reign putting the kingdom back together again. We will rejoin the Hittites later in this chapter, to discuss the achievements of their greatest king, Suppiluliumas I, after looking at what the rest of the Middle East was doing between 1500 and 1100 B.C.

The Hurrians

In the migrations of the second millennium B.C., one tribe was able to claim land in Mesopotamia by moving in gradually, without making a fuss among the previous owners. These were the Hurrians, who would now play a major role for the rest of the period covered in this chapter.

The actual origin of the Hurrians is not clear. We have translated enough of their language to know it was neither Semitic nor Indo-European. Some have proposed that both Hurrian and Elamite are extinct members of the Northeast Caucasian language family, which currently has about 3 million speakers among the ethnic groups living in the Caucasus mts. Wherever they came from, they started appearing in Mesopotamian records while the Akkadian Empire was in charge. In most cases we simply see them as Hurrian names in a list that is otherwise Sumerian and Akkadian, suggesting that they immigrated into the Tigris and Euphrates valleys, a few individuals at a time. The only places where there were enough of them to form a majority were northeast of the Tigris, where the modern city of Kirkuk now stands, and at the headwaters of the Khabur River, in northeast Syria. In the latter location they founded a city named Urkesh, which was discovered in 1984, but not identified until 1995.

Urkesh probably first saw settlement in the early third millennium B.C., but the oldest buildings and artifacts found so far date to about 2400 B.C. As Mesopotamia's northernmost city, it managed to escape Akkadian domination; it was allied with King Naram-Sin, instead of being conquered by him. Besides the usual palace and a temple to the god Kumarbi (the temple was small, but built on a massive terrace), the city had an unusual feature--a deep well just south of the palace, containing the bones of piglets and puppies. Hurrian texts preserved by the Hittites, centuries later, tell us that Hurrians sacrificed these animals to the gods of the Netherworld, in hollow circles called a:bi. This pit must have been such an a:bi, constructed to allow humans to get closer to the spirits they were attempting to contact.

Under the Amorite kingdoms and the Babylonian Empire, the occurrence of Hurrian names in Mesopotamian records increased steadily. To the northeast, they established several small communities between the Tigris River and the Zagros mts., though at this stage they were not yet ready to take over. In fact, Urkesh was abandoned around 1600 B.C. and not rebuilt for 300 years, presumably because it had been conquered by either Assyria or Mari.(7) After Hammurabi's reign, the Hurrians expanded to Syria and the Mediterranean, settling around Alalakh (near ancient Antioch, modern Antakya), and in Kizzuwatna (southern Turkey, later called Cilicia), where soon they would run into the Hittites. In Syria they also got their first chance to rule something larger than a city-state--the Hurrian-Amorite kingdom of Yamhad. Yamhad was conquered by Mursilis I when he marched against Babylon, but by then much of the Hurrian culture had spread to the Hittites; Hittites and Hurrians followed the same gods, the Hittites wrote epic poems based on Hurrian mythology, and more than one Hittite queen had a Hurrian name.

Two new Hurrian kingdoms rose up in the aftermath of Babylon's fall. The community at modern Kirkuk became the kingdom of Arrapha; most of what we know about the Hurrians comes from 4,000 clay tablets excavated at Nuzi, a city close to Arrapha. An even larger kingdom, called Mitanni, was founded on the Khabur River, a tributary of the Euphrates, by a legendary king named Kirta, around 1350 B.C. However, nothing definite is known about Kirta or his son, Shuttarna I.

In fact, we don't have a clear history of the kingdom anywhere. Our sources for information on Mitanni are clay tablets from Assyrian, Hittite and Egyptian libraries, and a few inscriptions in Syria. It also doesn't help that every nearby civilization had a different name for the Hurrians and their kingdom; the Assyrian name for Mitanni was Hanigalbat, the Egyptian name was nhrn or Nahrin, the Old Testament calls the land Aram-Naharaim, and the Hittites simply called it the land of the Khurri or Hurri. Consequently we know the names of the most important Mitannian kings, but we have to put question marks around all dates, and aren't even certain what order the kings were in.(8) Equally mysterious is the location of Mitanni's capital, Washukkanni (also spelled Vasukhani, meaning "Mine of Wealth"), though most believe the site for it is Tell al-Fakhariyeh in northeastern Syria.

Like the Hittites, Mitanni appears to have had a mixed population; in this case, the population was mostly Hurrian, lorded over by an Indo-European elite. This in itself isn't a surprise, because the rulers of Mitanni used horses and chariots. In other places where we see a chariot revolution, like Anatolia and India, those responsible for introducing them were usually Indo-Europeans. Further evidence of an Indo-European connection comes from the language they spoke, which closely resembled Avestan, an old Iranian language, and a religion that combined Teshub, the Hittite weather-god, Mesopotamian deities like Ishtar and Nergal, and some Indo-Aryan gods like Indra, Varuna and Mitra (the latter are also mentioned in the Vedic literature of ancient India).

The rulers of Mitanni were most likely close relatives of the Urartians, the ancestors of the Armenians, and the Kassites. Before long, however, they were assimilated into the language and culture of their subjects. Immanuel Velikovsky suggested in Ramses II and His Time that Mitanni was simply another name for the Medes; whether or not there was a Mitannian-Median connection, both peoples were Indo-Iranians, and they lived in the same general area.

Because the Hittites and Assyrians were currently in eclipse, the third king of Mitanni, Parattarna, conquered the northwestern Syrian city of Aleppo and made Idrimi of Alalakh his vassal. This gave the kingdom access to the Mediterranean. He was followed sometime in the thirteenth century B.C. by Sausatatar (also spelled Shaushtatar), Mitanni's greatest king. Under Sausatatar the kingdom took Kizzuwatna and Ishuwa (western Armenia) from the Hittites and looted Assur, making the Assyrians another vassal state. On a modern-day map Mitanni now ruled most of Syria, the southeastern quarter of Turkey and northern Iraq, making it the most powerful nation in the Fertile Crescent. It managed to stay on top for at least a century, but in a place like the Middle East, someone would eventually come along and knock the Mitannians off. When that happened the challenger came from an unexpected direction; it was not the Hittites or the Assyrians, but a nation that normally kept to itself--Egypt.

The Kassites

The Kassites were another Indo-European tribe, which migrated out of the Zagros mts., in the neighborhood of modern Luristan, during the post-Hammurabi years. Like the Hurrians, they filled in a vaccuum left by their predecessors, but got involved more quickly; they make their first appearance in Babylonian documents in 1514 B.C., just eight years after Hammurabi's death. In that year Gandash, the first Kassite king on record, attacked Babylon. Samsu-iluna, the king of Babylon, beat off the attack, but apparently Gandash was able to settle somewhere in northern Babylonia. The third Kassite king, Kashtiliash I (1477?-1456? B.C.), established himself at Hana, a town at the junction of the Euphrates and Khabur Rivers, two hundred miles upstream from Babylon.

A wave of Kassite immigration into Mesopotamia took place during the 150 years after Gandash; most settled down as farmers and mercenaries, and gradually won acceptance for themselves. Then in the aftermath of the Hittite raid, the leading Kassite of the day, Agum II, claimed the Babylonian throne, apparently without opposition. To make himself more legitimate than the Hittites and his Kassite predecessors, he returned the statue of Marduk to Babylon, and gave Marduk equal status with Shuqamuna, the main Kassite god. His dynasty would rule for the next 346 years (1362-1016 B.C.), making it one of the longest-lived in Babylonian history.

The Old Testament records a brief occupation of Israel by a Mesopotamian king, one Cushan-Rishathaim ("Doubly Wicked Cushan"), in the 14th century B.C., no more than a generation after Joshua (Judges 3). We have not identified this invader from Mesopotamian records, but many Kassite kings had similar-sounding names (Kashtiliash and Kadashman-Turgu, for instance). On the other hand, if you go by dates, Agum II becomes the best candidate for the Mesopotamian oppressor.

Around 1250 B.C. the Kassite king Ulamburiash crushed the Marsh Kingdom, bringing the south back under Babylonian rule. Otherwise, though, the Kassites appear to have been peaceful monarchs. This viewpoint may change at a later date, as more Kassite-era clay tablets are translated. Currently it appears that historians are guilty of ignoring the stable Kassite kingdom, and concentrating their attentions on the more exciting empires of Hammurabi, the Assyrians and Nebuchadnezzar (see also Chapter 4, footnote #8).

Once in power the Kassites learned to behave like good, responsible Mesopotamians. Order returned, and they repaired damaged temples. Nippur was picked to be the main administrative center of the south, so under the Kassites the former Sumerian holy city regained much of its former splendor. They also dedicated themselves to restoring the other dead cities downstream; irrigation canals dug in the Kassite period did not follow the natural contours of the land, but cut directly across hills to connect the new course of the Euphrates with still-venerated places like Ur. Because the Kassites did not have any new labor-saving devices, this project required an enormous labor effort, which had to be maintained afterwards to keep the new canals from silting up. The fact that the Kassites managed to do it tells us that like the Egyptians in the pyramid-building era, the Kassites had a stable society, a thriving economy, and a large submissive population available for the job. But until more information about them is published, we'll have to leave the Kassites. Next we will go to the other end of the Fertile Crescent, to look at the origins of the most important nation in Middle Eastern history.

The Eleventh Plague

In the first chapter of this work we looked at the background of the man who began the restoration of monotheism, Abraham. Nearly two centuries later one of Abraham's great-grandsons, Joseph (1701-1591 B.C.), came to Egypt, where he rose from bondage to become the prime minister, with an Egyptian name (Zaphnath-Paaneah) and an Egyptian wife. Later a famine causes the rest of the family to join him. Normally we date this to the Hyksos Period of Egyptian history, presumably because an Asiatic pharaoh would have been more friendly to immigrants from the east. It is possible, however, to make a case for putting the story of Joseph right at the peak of the Middle Kingdom, in the XII dynasty. My reasons for this are as follows:

a. The Hebrews were settled away from where the Egyptians lived, because "shepherds were an abomination to the Egyptians." Such immigrants wouldn't have offended a "Shepherd King," as we sometimes call the Hyksos. In fact, excavations at Tell ed-Daba, ancient Avaris, show that the eastern part of the Nile delta was largely populated by Middle Eastern tribes like the Amorites, as far back as the First Intermediate Period (about 2000 B.C.). However, if I read Ezekiel 20:5-9 correctly, the Israelites may also have fallen into idolatry during the years between Joseph and Moses. As a result, the Israelites would have to leave Egypt before they were completely assimilated.

b. Several famines were reported during this period, including a major one during the reign of Senusret III, my own candidate for Joseph's patron. While this isn't the only famine recorded in ancient times, it does strengthen the case.

c. At an uncertain date, but during the XII dynasty, the Egyptians dug a canal from the Nile to irrigate the Faiyum, a depression southwest of Cairo. The modern name of that canal is "Bahr Yusef" (Joseph's Canal), suggesting that Joseph, and not a pharaoh, was responsible for making this part of the Libyan desert green.

d. Somebody in the Middle Kingdom tried using the formal Egyptian writing system, the famous hieroglyphics, to write in another language. In 1999 archaeologists John and Deborah Darnell discovered a fascinating inscription, in an Egyptian valley called the Wadi el-Hol. Dated to the early XII dynasty (around 1800 B.C.), the symbols do not make sense when read like an Egyptian inscription, but appear intended for use with a Semitic language, most likely Canaanite; it has been suggested this was carved by Canaanite mercenaries employed in the Egyptian army. More evidence of the development of the first alphabet has been found at Serabit el-Khadim, the most important turquoise mine that Egyptians operated in the Sinai. This site was busiest during the reigns of Senusret III and Amenemhet III (1698-1634 B.C.), which included the building of a temple to Hathor, the patron goddess of the mine. Among numerous Egyptian inscriptions in the temple and the mine, done in hieroglyphics and simpler Hieratic script, are four graffiti inscriptions, usually dated around 1500 B.C., which used about thirty hieroglyphics to represent sounds rather than words; the crude appearance of the inscriptions suggest that they were not done by an Egyptian scribe. Is this where the development of the Hebrew alphabet got started? Whether or not it is, we do know that some of those working here came from Asiatic tribes; Sir Alan Gardiner went so far as to identify them:

"Towards the end of the dynasty [12th], under Ammenemes III, the brother of the prince of Retenu was assisting [?] the Egyptians in the turquoise-workings of Serabit el-Khadim in the peninsula of Sinai...." (Egypt of the Pharaohs, Oxford University Press. N.Y. 1961, pg. 131).

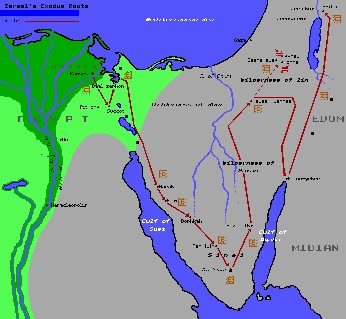

Retenu is the ancient Egyptian name for the Holy Land, and if the chronology used here is accurate, then the "brother of prince of Retenu" could be a character mentioned in the Book of Genesis, like Jacob's brother Esau. Since mine workers were often slaves and prisoners, some of the Hebrews enslaved in the Exodus story could have ended up here. That may explain why so many maps showing the route of the Exodus (see below) put one of the campsites, Dophkah, on the same spot as Serabit el-Khadim; Moses could have stopped by to pick up his countrymen working in the mine.

After the prosperous XII dynasty came the turbulent XIII and XIV dynasties, which the author believes included the time of the Exodus. The story of how the Israelites came out of Egypt is so widely known that there is little need to repeat it here. They were led by God and a man of remarkable intelligence and ability, Moses. A series of disasters brought Egypt to its knees, which we remember as the ten plagues. The Israelites took advantage of this setback to Egypt and fled from the Nile Delta, leading to one of the most famous encounters of the Old Tedstament. Traditionally it has been believed that the Israelites ditched the Egyptian army on the shore of the Red Sea, but the Hebrew name for the body of water, Yam Suf ("Sea of Reeds") suggests it was more likely one of the bitter lakes in the Isthmus of Suez. Wherever it happened, the Egyptians were left devastated and without an army, so they were an easy target for the manmade disaster which now followed the natural ones--chariot-using raiders. These were called Hyksos by Greek-speaking historians, and Amu by the Egyptians. In one of her inscriptions, Egypt's greatest queen, Queen Hatshepsut (1138-1116 B.C.), also referred to a foreign elite among the Amu, which she called the Shemau.

Efforts have been made to identify the Hyksos over the years, and no proposal has convinced everybody. Josephus, the famous Jewish historian of the first century A.D., looked at the story of the Hyksos by Manetho, and Egyptian who lived about three hundred years earlier, and thought that the Hyksos were one and the same with the Hebrews. More recently most scholars have seen the Hyksos as Canaanites, or at least some West Semitic group, coming from either Syria or Canaan. In one inscription, Kamose, the last pharaoh of Egypt's XVII dynasty, referred to Auserre Apepi (Apophis), the second-to-last Hyksos king, as a "Chieftain of Retenu" (Reteneu was the Egyptian name for Canaan). For some scholars this is enough evidence to give the Hyksos a Canaanite origin. Others have looked for an Indo-European origin, because the only description of the Hyksos the Egyptians gave us is that they had red hair and white skin--invaders like this are not too likely if they only came from the Arabian peninsula or the Fertile Crescent. Still others have suggested a Hurrian element, because Mitanni was the closest major nation to Egypt at this time. Finally, some have pointed to a Hyksos king named Khyan, and suggested that his name should be read as "Hayanu," which was an Amorite name used centuries earlier; the Assyrian king Shamshi-Adad I had an ancestor by that name.

In the Old Testament, one group appears at the right time and place to match these raiders, an Arabian tribe called the Amalekites. The Amalekites stormed across the Sinai Peninsula, picked a fight with the Israelite ex-slaves they met there (Exodus 17), and moved on into Egypt. In the Nile valley they fell upon the devastated Egyptians like an eleventh plague, conquering the land with almost no fighting at all.

Afterwards the Amalekites settled in the former Israelite home, making Avaris their capital. The eastern delta and the nearby city of Memphis remained attractive places for Asiatics to live; pottery found in this area from the Second Intermediate Period followed styles that are more in common with Canaanite pottery than with the Theban-style pottery used in Upper Egypt. But even when following pottery, attempts to identify the Hyksos as one ethnic group, whether the Amalekites or anybody else, have so far not convinced everybody. The easiest way to explain this is that they were not one tribe for long. The original (and largest) component would have been Semitic; some of them were probably living in the Nile delta already, before the Amalekites moved in and seized power. In "The Lords of Avaris," David Rohl calls this group the "Lesser Hyksos," and suggests that their rulers were recorded as Egypt's mysterious XIV dynasty.

Manetho, the ancient Egyptian historian, assigns the XV dynasty, not the XIV, to the Hyksos, and he credits it with six kings that ruled for 13, 44, 36, 61, 50 and 49 years, respectively. This is almost certainly an exaggeration, a case of "cooking the books." Once in a while you can expect to see a very long-lived king, like Ramses II, but having several in the same family is hard to believe, especially before the modern era, when medicine was so primitive that the average person wasn't likely to live past his thirties. Furthermore, if a long-lived king is succeeded by his son, the son will be at least middle-aged when he takes over, so don't expect him to wear the crown as long. To give a modern example, England's Queen Elizabeth II has been on the throne for sixty-one years as I write this, and Prince Charles is sixty-four years old, so he will have to live to be at least 125 to reign for as long as his mother did--not bloody likely! Finally, the typical monarch of the ancient world was aware of his mortality, and might crown his heir while is still alive, to give the co-regent some "on-the-job training." Therefore, when you see a reign of forty years or more, expect it to have a co-regency at the beginning of the reign, the end, or even both. King lists were usually to give the impression that every king ruled alone, though. A portion of the fragmentary Turin Canon, our most reliable ancient list of the pharaohs, records six foreign kings that ruled for a total of 108 years, and this is now seen as the correct length of the XV dynasty (1290-1183 B.C. on this chronology).

The story of the Hyksos was known to the Greeks, who attempted to link it to the expulsion of an Egyptian king named Belus (Baal?) in their own mythology and to the story of Danaus, the founder of the Argive dynasty. This may be the Indo-European element we were looking for; David Rohl calls this group the "Greater Hyksos," to distinguish them from the "Lesser Hyksos" that had ruled previously. The most important clue comes from Akrotiri, a city on the Aegean island of Thera that was buried in ash by the explosion of the island's volcano in the second millennium B.C. Elsewhere on this site, that fateful eruption is credited with destroying the Minoan civilization, and starting the Atlantis myth. A two-story building in Akrotiri, called the "West House" by the excavators, has a series of murals running around the walls of one room, that seem to describe an expedition from the Aegean to Egypt and back again.

The first scene shows boats setting sail from a town that is probably Akrotiri itself. There is a shipwreck as the boats approach a mountainous shore, and then the next scene after that shows two leaders and their retinue chatting on top of a mountain, one of the groups in costumes that were fashionable in the Aegean. We take this to mean that the fleet landed somewhere on the Levantine coast, the commander met the local ruler, and they joined forces for the next part of the journey. Then we see warriors marching toward a city, carrying large shields and spears and wearing helmets made from boar tusks. This could be an important town they captured on the Mediterranean coast, before continuing to Egypt; Ugarit, Byblos, Gaza or Sharuhen are all possibilities.(9)

The next scene is a lush landscape around a meandering river, with palm trees, papyrus reeds and various animals. Only one place near the Mediterranean fits this description--the Nile valley. After this are two more scenes, each showing the fleet and a city. One shows a city in a river delta, and the ships departing from it are more elaborate than the ships shown up to this point; could this be a Nile delta city like Avaris, the Hyksos capital, and the adventurers are leaving, after getting rich in Egypt? Then with the final scene, the fleet returns to its point of origin (Akrotiri again), where a crowd has come out to welcome them.

From the mural we can put together the following picture. First the Amu or Lesser Hyksos seized power; the Amalekites invaded and easily conquered Egypt, possibly with the help of any Asiatics who did not leave the Nile Delta when the Israelites did. Later on, a fleet carrying Minoan and/or Greek warriors assembles in the Aegean and sails to Egypt, picking up some allies on the way. These become the Shemau or Greater Hyksos, and six of their leaders rule Lower Egypt under the XV dynasty. While it is unusual for members of several nations in ancient times to get together to accomplish some enterprise, in view of how difficult it was to overcome language barriers, it is not impossible; we'll see it happen again with the "Peoples of the Sea" in the next chapter. The Hyksos stay in Egypt for quite a while, and when they finally leave, they are wealthier than when they arrived. Their fleet, carrying the last Hyksos king, returns to the Aegean port it started from.

Whoever the Hyksos were, once settled in the Nile valley, they only ruled Lower Egypt directly; upstream they let a native governor (the XVI & XVII dynasties) rule in Thebes to keep the tribute coming in. In the Levant, before the Israelites arrived, they also established control, building large earthen enclosures for their horses at Jericho, Shechem, Lachish, and Tell el-Ajjul (Sharuhen?). But here they left Canaanite kings in charge; as in Upper Egypt, they preferred to rule by proxy. Scarabs bearing Hyksos names like Apopi(10) and Khyan, and Hyksos cult objects (nude figurines, serpents and doves) have been found in Syria, Lebanon, and even near Lakes Urmia and Van, showing how influential they must have been.

For the intruders, the good times ended with a change of native rulers upstream; the compliant XVI dynasty was replaced by the uppity XVII dynasty, which had learned how to use the weapons and tactics of their enemies. With some help from the Nubians, who struck Egypt from the opposite direction at the same time, the Hyksos won the first rounds; one XVII dynasty pharaoh, Kamose, besieged Avaris with a fleet of riverboats, but failed to take the city. However, the Egyptians returned to try again when the next pharaoh, Ahmose, came of age. Still, taking a walled city in the bronze age was no easy task, and in the end Ahmose agreed to a negotiated settlement; he let the Hyksos leave when they couldn't take it any more. Manetho claimed that Ahmose chased them as far as Sharuhen in the southern part of the Holy Land, but as we can see from the West House murals, some of them sailed to the Aegean instead. If Rohl's theory of the Hyksos being a multinational force is correct, after they were expelled from Egypt, the Greater and Lesser Hyksos separated and returned to the lands of their ancestors.

Finally, we mentioned above that the Greeks saw the Hyksos among their ancestors. We may have a clue to that in the shaft graves Heinrich Schliemann (see the next chapter) excavated at Mycenae in 1874. Here he found skeletons adorned with gold treasures, including three golden masks; he called the most impressive item "the Mask of Agamemnon," though it probably belonged to a king who lived several centuries earlier. This is not a typical Greek burial; normally the Greeks cremated their dead. However, we know from the tomb of Tutankhamen that the Egyptians buried their dead with the richest grave goods they could afford. If some of the Hyksos went to Greece after they quit Egypt, did they bring the mummies of their ancestors with them, the way the Israelites took the mummy of Joseph during the Exodus, and re-bury them at the end of their journey? If so, Schliemann may have found the final resting place of the XV dynasty kings; the reason why he found skeletons instead of mummies is because Greece has a climate too wet to preserve the dead as easily as it is done in Egypt.

Israel Becomes a Nation

While the Hyksos subjugated Egypt, for forty years (1447-07 B.C. on my chronology) the Israelites wandered in the Sinai, Negev, Arabia, and finally the Jordanian desert.(11) After defeating the two Amorite kings on the east bank of the Jordan, Moses died and Joshua took command. He led the invasion of the Promised Land, and the central highlands of Judaea, Samaria, and Galilee were conquered before he retired. Each tribe still had the task of conquering the rest of its inheritance, but their performance was mediocre; they never drove the Canaanites and Philistines out completely, and the Israelites found themselves forced to live alongside them. Eventually, the Bible tells us, the Canaanites would become a sort of "Palestinian problem" for the Israelites, stirring up trouble and luring the Israelites into their own religion, which glorified sex and child sacrifice.

(A thumbnail, click on the picture to see it full size in a separate window.)

The next three and a half centuries are covered in the books of Judges and Ruth. The author of Judges described a cyclic pattern in Israel's fortunes: Israel slips into idolatry; they fall into bondage at the hands of an enemy; a leader emerges to drive out the enemy; that leader serves as a judge over Israel for the rest of his or her life; a new generation arises that does not remember the last victory; Israel goes back to idolatry, and the cycle begins again. The author of Judges summed up the general lawlessness of the period with these words: "In those days there was no king in the land of Israel, every man did what was right in his own eyes."

After the Amalekites lost their Lower Egyptian base, they returned to the Sinai. However, they still claimed the Holy Land, for the book of Judges has several verses mentioning the Amalekites aiding the enemies of Israel (3:15, 5:14, 6:3, 6:33, 7:12, and 10:12, plus a territorial claim in 12:15). That, along with their first attack on the Israelites while they were leaving Egypt, marked them for total destruction when Israel got its first king.(12)

The Warrior Pharaohs

For most of its ancient history Egypt cared little about what happened in the rest of the world. We noted in Chapter 1 that Egyptians rarely visited other parts of the Fertile Crescent, and before 2000 B.C., the only military activities the Egyptians carried out in Asia were raids for loot. We also hear of a military campaign under Senusret III (1696-1658 B.C.), the pharaoh at the height of the XII dynasty, and it involved a battle at Shechem; this may have been the same affair as the funeral procession for Jacob recorded in Genesis 50 (at least the dates for both events seem identical).

That changed when the Egyptians recovered from the Hyksos oppression. Now they realized that their desert frontiers would no longer keep all invaders out, and that for security's sake they might have to conquer the lands of their enemies. The XVIII dynasty produced several militant pharaohs, and under their leadership Egypt became an empire.

The first aggressive pharaoh after Ahmose, the founder of the New Kingdom, was Thutmose I (1150-1139). He led an expedition into the Holy Land, but it appears to have been just for show; he didn't fight any battles, and went home after leaving a stela at the farthest point he reached--the bank of a river. This was either the Jordan or the Euphrates, and it gave the Egyptians quite a surprise. The only river they were familiar with, the Nile, flows from the south to the north, but the Jordan runs in the opposite direction! Back in Egypt Thutmose's soldiers never got tired of telling about "that inverted water which flows southward when [it ought to be] flowing northward." The next generation was mostly peaceful, because the next pharaoh, Thutmose II, was in poor health, and his wife and successor, Queen Hatshepsut, was more interested in building temples and shopping (e.g., the Punt expedition) than in leading armies.

When Thutmose III became pharaoh, he promptly mobilized Egypt's armed forces. Several city-states of the Levant had paid tribute to Egypt since the time of Thutmose I; now that a young, inexperienced king sat on Egypt's throne, they put him to the test by forming an anti-Egyptian alliance, with the kingdom of Mitanni offering support. Leading the alliance was Kadesh, a Syrian city believed to be identified with Tell Nebi Mend on the Orontes River(13). In March of 1116 B.C., just two months after Hatshepsut's death, he set forth with his army into Asia. After passing through Gaza, which had remained loyal, he followed the coast to Yehem, at the foot of Mt. Carmel. There he learned that the king of Kadesh was preparing a defensive position near Megiddo, which commanded the western entrance into the Jezreel valley. Three possible routes led from Yenem to Megiddo, so Thutmose called a council to plan the next move. The shortest and most direct path, going through Aruna Pass, was by far the most dangerous, and the cautious generals pointed out that in the pass the way was so narrow that the army would have to march "horse after horse and man after man," offering the enemy a superb chance for an ambush. Nevertheless, Thutmose declared he would take this road, for reasons of prestige: "They will say, these enemies whom Ra abominates, `Has His Majesty set out on another road because he has become afraid of us?'--so they will speak."

Maybe it was a matter of pride, but as it turned out, it was also a good military decision. The perilous Aruna Pass was not the route the Egyptians were expected to take, so it was left unguarded. When Thutmose and his army made it through the pass without incident, the battle was as good as over.

The battle that took place the next day (the first of many that would be fought on the plain of Armageddon over the ages) was a rout; 83 Canaanites were killed, 340 were captured, and the rest fled to Megiddo. When the soldiers of Kadesh got there the king of Megiddo had already shut the gates of the city against the Egyptians, so they--including the king of Kadesh--had to knot their clothing into ropes and haul themselves over the town walls. The Egyptians plundered the military camp outside of the city, and reported capturing 924 enemy chariots and 200 suits of armor (mostly leather suits covered with bronze scales at this date). However, they had no siege equipment, so after they reached the walls of Megiddo it took seven months to starve the town into submission.

The King of Kadesh paid tribute, and Thutmose went home with an enormous booty, which included livestock,--and 87 children of Asian nobles, who were given an Egyptian education so they could return as pro-Egyptian governors when they grew up. Thutmose later said that the fall of Megiddo equaled "the capture of a thousand cities," and regarded it as his greatest triumph.

The pharaoh's military ambitions were not satisfied, though. During the rest of his reign, he led fourteen more campaigns into Asia, winning every time. The second, third and fourth campaigns were merely follow-up missions; he fought no battles, and took tribute from the cities that submitted after the first campaign. For the fifth campaign he captured the ports of Phoenicia; this allowed him to transport his troops by water after this, dramatically reducing travel time. His sixth and seventh campaigns were devoted to conquering Syria; he finally took Kadesh in 1109 B.C. Now his main adversary was Parsatatar, the king of Mitanni. For this challenge he had boats hauled overland from Arvad to Carchemish, defeated the Mitannian ships defending the Euphrates, and crossed that river to raid the kingdom. It appears that Parsatatar was taken by surprise, because he did not engage Thutmose in battle, and had only 636 soldiers available, which the Egyptians captured. After that, Thutmose was pretty much able to go wherever he wanted as he devastated Mitanni's homeland, bragging that he turned it "into red dust on which no foliage will ever grow again." When the other nations of the Fertile Crescent heard the news, they hastily dispatched gifts to the conqueror (tribute from Babylon and the Hittites is listed with the booty Thutmose brought back). More Syrian cities surrendered in the following year, and even the island of Cyprus sent tribute.(14)

On the way back the pharaoh heard about a herd of 120 elephants nearby, in the rocky pools of Niy. A royal hunt was arranged for the troops, and there the king nearly met disaster. One infuriated beast charged Thutmose and would have killed him had not Amenemhab (see footnote 13) rushed to the rescue and struck off the elephant's trunk with his sword, "while standing in the water between two rocks."

No new land was conquered in the remaining campaigns of Thutmose. Most history books and atlases with maps from the mid-XVIII dynasty show the Egyptian-Mitannian border at the Euphrates River, but the frontier wasn't that simple; Ugarit was conquered by Egypt but not Aleppo and Alalakh, for instance. A fuzzy line running just north of Qatna on the Orontes, one that allows for clashing spheres of influence, would be more accurate. This was because Syria was too far away for Thutmose to rule it directly with an Egyptian governor, the way he did with Nubia. It wasn't even feasible to station permanent troop garrisons there, because of the Egyptian reluctance to spend long periods of time away from the Nile valley, something we noted in the previous chapter. Consequently, pharaohs like Thutmose left native monarchs in charge of the cities of the Levant, and were content as long as these minor kings paid tribute regularly. What is sometimes called the "Egyptian Empire" was really a network of pro-Egyptian satellite states.

The next pharaoh, Amenhotep II (1085-1059 B.C. on the author's chronology), was not a great man, but he was a big one. He boasted constantly of his athletic achievements, and appears to have gone into Asia mainly to prove what a superjock he was. A large bow that he claimed no one else could draw was found buried with him, in his sarcophagus. He went on four Asian campaigns; in the first one, he killed seven princes of Kadesh and brought their bodies back to Egypt, hanging head-down from the prow of his ship. Another campaign, however, had a bizarre report; one day after he crossed the border into Israel, a battle was fought with the following results:

"List of that which His Majesty captured on this day: his horses 2, chariots 1, a coat of mail, a quiver full of arrows, a corslet and--"

Then he turned around and went back to Egypt. In typical ancient Oriental fashion, this was another "victory," but it is more likely that Amenhotep barely escaped the battle alive; the items listed weren't really war trophies, but things that happened to be in the getaway chariot!

By 1077 B.C., Egypt and Mitanni were tired of fighting, and both were growing concerned about the rising power of the Hittites, who had gotten their act together by this time. The latter years of Amenhotep II's reign saw an alliance with Mitanni replace the previous antagonism. The next two Mitannian kings, Artatama I and Shuttarna II, gave their daughters in marriage to Amenhotep's successors, Thutmose IV and Amenhotep III; Shuttarna also made an official visit to Egypt. Some believe that two of Amenhotep IV's wives, Kiya (the mother of Tutankhamen) and even the lovely Queen Nefertiti, may have been Mitannian princesses as well. Our main source of information at this point are the Amarna letters, a collection of clay tablets containing messages from foreign leaders to Amenhotep III & IV, and they show an empire going to seed because of Egyptian inaction. When the Hittites and Assyrians went back on the warpath, vassals of Egypt pleaded for help that never came, because the eccentric Amenhotep IV, now renamed Akhenaten, was too preoccupied with his religious reforms to even care. Another challenge to Egyptian authority came when a local warlord named Labayu rose up in central Canaan; it now appears that Labayu was another name for Saul, the first king of Israel. On that note, the imperial period of Egypt's history, which began with a bang, ended with a whimper.(15)

This is the end of Part I. Click here to go to Part II.

FOOTNOTES