| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Europe

Chapter 2: CLASSICAL GREECE, PART II

1000 to 197 B.C.

This chapter is divided into two parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| What Made Classical Greece So Special? | |

| The Archaic Period | |

| Colonization | |

| Aristocracy, Oligarchy, and Tyranny | |

| Militant Sparta | |

| The Athenian Road to Democracy | |

| The Persian Wars | |

| Why the Greeks Won |

Part II

| Athenian Democracy | |

| Greek Medicine | |

| Hellenic Poetry and Drama | |

| Hellenic Architecture, Sculpture and Pottery | |

| Athenian Society | |

| Athenian Imperialism | |

| Athenian-Spartan Rivalry | |

| Go to Page Navigator |

Part III

| The Peloponnesian War | |

| Spartan and Theban Ascendancy | |

| Philip of Macedon | |

| Alexander the Pretty-Good | |

| Alexander's Empire Up For Grabs | |

| Hellenistic Devolution |

Part IV

| Pre-Classical Greek Religion | |

| The Early Philosophers | |

| The Sophists and Socrates | |

| Plato and Aristotle | |

| Other Developments in Greek Philosophy |

Athenian Democracy

The part they played in defeating the mighty Persian empire exhilarated the Athenians and gave them the confidence and energy that made them the leaders of the Greek world for the rest of the fifth century B.C. The forty-eight years between the Persian Wars and the Peloponnesian War are glorified in most history books as the Golden Age of Greece, when the Athenians "attempted more and achieved more in a wider variety of fields than any nation great or small has ever attempted or achieved in a similar space of time."(21) Athens was adorned with magnificent temples, gymnasiums, theaters, and other public buildings. Many of the greatest Greek artists, writers and thinkers lived in Athens during this time: Phidias, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Hippocrates, Herodotus, Thucydides, Anaxagoras, and Socrates.

The first years were easy ones from a political standpoint, because Sparta was weak and friendly.(22) In 470 Themistocles was ostracized because many Athenians thought he was letting success go to his head; he found a comfortable home among the Persians in the town of Magnesia, where he spent the rest of his days. Cimon, the son of Miltiades, became the new head man of Athens.

In 464 a severe earthquake devastated Sparta, and the oppressed helots seized the opportunity to revolt. The Spartans suppressed most of them quickly enough, but one group entrenched itself at Mt. Ithome in Messenia and resisted the clumsy Spartan efforts to dislodge it. Sparta's allies came to her aid, and Sparta even asked Athens for assistance. Cimon compared Athens and Sparta to a pair of oxen when he said in a speech, "Will you stand by and see Greece hobbled, and Athens without her yokemate?" They voted to help, and 4,000 Athenian hoplites marched to Sparta. However, these hoplites were men full of radical democratic ideas, and once the Spartans learned that they favored human rights, they feared the Athenians would switch sides. Sparta sent the Athenians home before they took part in any fighting, and put down the rebellion on its own.(23)

Cimon fell out of favor because of this fiasco. Leading conservatives were put on trial for corruption, and in 461 Cimon was ostracized. As he left, the democrats reduced the power of the Areopagus (the assembly of the rich from aristocratic days), so that all it could do was advise, and perform minor judicial and religious functions. Then they reduced the property requirements formerly imposed on all public officials to a mere token sum, allowing any freeborn male in Athens to fully participate in the government. The radicals now dominated Athens, and their leader was a nephew of Cleisthenes--Pericles. For the next thirty-two years (461-429 B.C.), Pericles was Athens' greatest statesman, dominating the city with nothing but his ability to persuade others. Because of him, the Golden Age of Athens is also called the Periclean Age.(24)

Under Pericles the Athenian democracy achieved its fully developed form. The main body was the popular assembly, which gathered on a hill called the Pnyx; the amphitheater where they met had 18,000 seats, and any citizen could participate. From the assembly came the jurors, and the Council of Five Hundred; members of both were chosen by lot, so that the most popular or the richest wouldn't serve every time. They allowed no lawyers on lawsuits or criminal cases, while anywhere from 251 to 2,500 jurors took part in a typical case. Jurors were placed in groups of ten, and a magistrate randomly gave out white and black marbles to each group; those who received a white marble went to work that day. The Council of Five Hundred set the Assembly's agenda, and each month fifty of its members were on duty, 24 hours a day (the Athenian calendar had ten months of 36 days each). Eight of the archons (judges) were elected, while the ninth, the Archon Polemarchos, came from what was left of the Athenian royal family. Nobody served a term lasting more than a year, and the only appointed positions were those which required special skills, like state architect and finance minister.

This total democracy did not have a chief executive; not even a president or prime minister. Instead, military matters and executive functions were run by a board of ten elected generals. These generals urged the Popular Assembly to adopt specific measures, and both their success and popularity determined whether they would be reelected at the end of their annual term. Pericles distinguished himself by leading a squadron of ships against both Sparta and Thebes in 457 B.C., and afterwards became a lifelong advocate of a strong navy. His prestige reached such heights that he won every election for thirty years in a row, and so great was his influence on the Athenians that, in the words of the contemporary historian Thucydides, "what was in name a democracy was virtually a government by its greatest citizen."(25)

For the first time, they made payment to citizens for performing public duties, allowing even the poorest to become jurors and members of the Council of Five Hundred. Attendance at civic meetings became a subsidy for the lower class. Only the army remained in the hands of the well-to-do, because each soldier was still expected to pay for his equipment; by contrast, the navy was overwhelmingly democratic, because most of its sailors were poor. Conservatives called the payments for political participation a form of bribery, but Pericles insisted that it was essential to the success of democracy:

"Our constitution is named a democracy, because it is in the hands not of the few but of the many. But our laws secure equal justice for all in their private disputes, and our public opinion welcomes and honors talent in every branch of achievement, not as a matter of privilege but on grounds of excellence alone . . . [Athenians] do not allow absorption in their own various affairs to interfere with their knowledge of the city's. We differ from other states in regarding the man who holds aloof from public life not as "quiet" but as useless; we decide or debate, carefully and in person, all matters of policy, holding, not that words and deeds go ill together, but that acts are foredoomed to failure when undertaken undiscussed."(26)

Greek Medicine

Superstitions about the human body blocked the development of medical science until 420 B.C., when Hippocrates, the "father of medicine," founded a school in which he emphasized the value of observation and the careful interpretation of symptoms. Such modern medical terms as "crisis," "acute," and "chronic" were first used by Hippocrates. He was firmly convinced that disease resulted from natural, not supernatural, causes. Writing of epilepsy, considered at the time a "sacred" or supernaturally inspired malady, one Hippocratic writer observed:

"It seems to me that this disease is no more divine than any other. It has a natural cause just as other diseases have. Men think it supernatural because they do not understand it. But if they called everything supernatural which they do not understand, why, there would be no end of such thing!"(27)

The Hippocratic school also gave doctors a sense of service to humanity which they have never lost. All members took the famous Hippocratic Oath, still in use today, which says things like: "I will adopt the regimen which in my best judgment is beneficial to my patients, and not for their injury or for any wrongful purpose. I will not give poison to anyone, though I be asked . . . nor will I procure abortion."(28)

Despite their empirical approach, the Hippocratic school adopted the theory that the body contained four liquids or humors--blood, phlegm, black bile, and white bile--whose proper balance was the basis of health. This doctrine impeded medical progress until modern times.

Hellenic Poetry and Drama

We can classify Greek literary periods according to the dominant poetic forms of the times. First came the time of epics, exemplified by Homer's two great works, the Iliad and the Odyssey.

As Greek society became more sophisticated, a new type of poetry, written to sing with a lyre, arose among the Ionian Greeks. Unlike Homer, authors of this lyric poetry sang not of legendary events but of present delights and sorrows. This new note, personal and passionate, can be seen in the following examples, in which the contrast between the new values and those of Homer's heroic age is sharply clear. Whereas Homer saw Arete (excellence) as the greatest virtue, Archilochus of Paros (seventh century B.C.) unashamedly throws away his shield so he can run from the battlefield:

"My trusty shield adorns some Thracian foe; I

left it in a bush - not as I would! But I have

saved my life; so let it go. Soon I will get

another just as good."(29)

While Homer imagined an unromantic, purely physical attraction between Paris and the abducted Helen, Sappho of Lesbos (sixth century B.C.), the first female poet on record, saw Helen as the helpless, unresisting victim of romantic love:

"She, who the beauty of mankind

Excelled, fair Helen, all for love

The noblest husband left behind;

Afar, to Troy she sailed away,

Her child, her parents, clean forgot;

The Cyprian [Aphrodite] led her far astray

Out of the way, resisting not."(30)

Greek drama began with the religious rites of the Dionysian mystery cult, in which a large chorus and its leader taught moral lessons through singing and dancing. Thespis, a contemporary of Solon, added an actor called the "answerer" to converse with the chorus and its leader. This made dramatic talk possible. By the fifth century B.C. in Athens, two distinct forms--tragedy and comedy--had evolved. Borrowing from the old familiar legends of gods and heroes for their plots, the tragedians reinterpreted them in the light of the values and problems of their own times.

In reworking the old legends of the heroic age, Aeschylus (525-456 B.C.) sought to spread the new religious values of his age, by showing how the old beliefs cause suffering. In his trilogy, the Oresteia, for example, he concerned himself with the murder of Agamemnon by his queen following his return from the Trojan War, and then went on to work out the consequences--murder piled on murder until people through suffering learn to substitute the moral law of Zeus for the primitive law of the blood feud. Like the prophets of Israel, Aeschylus taught that while "sin brings misery," misery in turn leads to wisdom:

"Zeus the Guide, who made man turn

Thought-ward, Zeus, who did ordain

Man by Suffering shall Learn.

So the heart of him, again

Aching with remembered pain,

Bleeds and sleepeth not, until

Wisdom comes against his will."(31)

A generation later, Sophocles (c. 496-406 B.C.) largely abandoned Aeschylus' concern for working out divine justice and concentrated upon human character. To Sophocles, a certain amount of suffering was inevitable in life. No one is perfect; even in the best people a tragic flaw causes them to make mistakes. Sophocles dwelled mainly on the way in which human beings react to suffering. Like the sculptors of his day, Sophocles viewed humans as potentially ideal creatures, and he displayed human greatness by depicting people experiencing great tragedy without whimpering--and sometimes triumphing over it in the end.

Euripides (c. 480-406 B.C.), the last of the great Athenian tragedians, reflects the rational and critical spirit of the late fifth century B.C. Instead of idealizing humanity, as Sophocles did, Euripides viewed human life as pathetic, the ways of the gods ridiculous. His recurrent theme was "Since life began, hath there in God's eye stood one happy man?" For this he has been called "the poet of the world's grief." Euripides has also been called the first psychologist, for he looked deep into the human soul and described what he saw with intense realism. Even Sophocles admired this; he once compared Euripides with himself by saying, "He paints men as they are, I paint men as they ought to be." Far more than the other playwrights, Euripides strikes home to us today. His Medea, for example, is a startling and moving account of a woman's exploitation and her retaliatory rage. When Medea's ambitious husband discards her for a young heiress, she kills her children out of a bitter hatred that is the dark side of her once passionate love:

"He, even he,

Whom to know well was all the world to me,

The man I loved, hath proved most evil. Oh,

Of all things upon earth that bleed and grow,

A herb most bruised is woman.

. . . but once spoil her of her right

In man's love, and there moves, I warn thee well,

No bloodier spirit between heaven and hell."(32)

Comedies were bawdy and spirited. There were no laws against libel or obscenity in Athens, so political satire became a favorite subject of the comedians. Aristophanes (c. 445-385 B.C.), the most famous comic-dramatist, brilliantly satirized Athenian democracy as a mob led by demagogues, saw the Sophists (among whom he included Socrates) as subversive, Euripides as an underminer of civic spirit and traditional faith, and the youth of Athens as irresponsible youngsters more interested in the latest fashions than in politics. Yet he also put intelligent messages between his jokes. For example, in his play Lysistrata, the women of Greece stop the Peloponnesian War with a sex boycott, refusing to sleep with their husbands until they agree to end the fighting; thus, he could advocate peace and women's rights in the same story. By allowing such ribald humor even in difficult times, the Athenians may have shown us why Athens remained a cultural center after its best years ended; they were never afraid of the truth, and could always laugh at themselves.

Hellenic Architecture

In the sixth century B.C. architecture flourished with the construction of large temples of stone. Their form was a development from earlier wooden structures influenced by the remains of Mycenaean palaces. Architecture, like so many other aspects of Greek culture, reached its zenith in Athens during the fifth century B.C.

For a generation after the Persian Wars, the Athenian Acropolis was left bare, to remind citizens of what the Persians did to their city. However, in 449 B.C. Athens finally signed a peace treaty with Persia, so Pericles launched a great building program, because he felt that the glory of the city should be expressed in some visible form.

The Parthenon, the Erechtheum, and the other temples on the Acropolis exhibit the highly developed features that make Greek architecture so pleasing to the eye. All relationships, such as column spacing and height and the curvature of floor and roof lines, were calculated and executed with remarkable precision to achieve a perfect balance, both structurally and visually; for example, they gave the columns a delicate curve so that they appear straight from a distance. The three styles of columns were the simple Doric, which was used in the Parthenon; the Ionic, seen in the Erechtheum; and the later and more ornate Corinthian. Unlike the temples of older civilizations, which were enclosed and mysterious places, the Greek temple was open, with a colonnade porch and a single room for a statue of the god. Sacrifice and ritual took place outside the temple, where the altar was placed.

Other types of buildings, notably the theaters, stadiums, and gymnasiums, also express the Greek spirit and way of life. With the open-air theaters, the circular shape of the spectators' sections and the plan of the orchestra section set a style that has survived to this day. In his Life of Pericles, Plutarch explained why classical Greek architecture is still appealing to us, even in its ruined state:

"And this is the more cause to marvel at the buildings of Pericles, that they were made in so little time to last for so long . . . Such a bloom of newness is there upon them, keeping them, to the eye, untouched by time, as though the works had blended into them, an evergreen spirit and a soul of unfading youth."

Hellenic Sculpture and Pottery

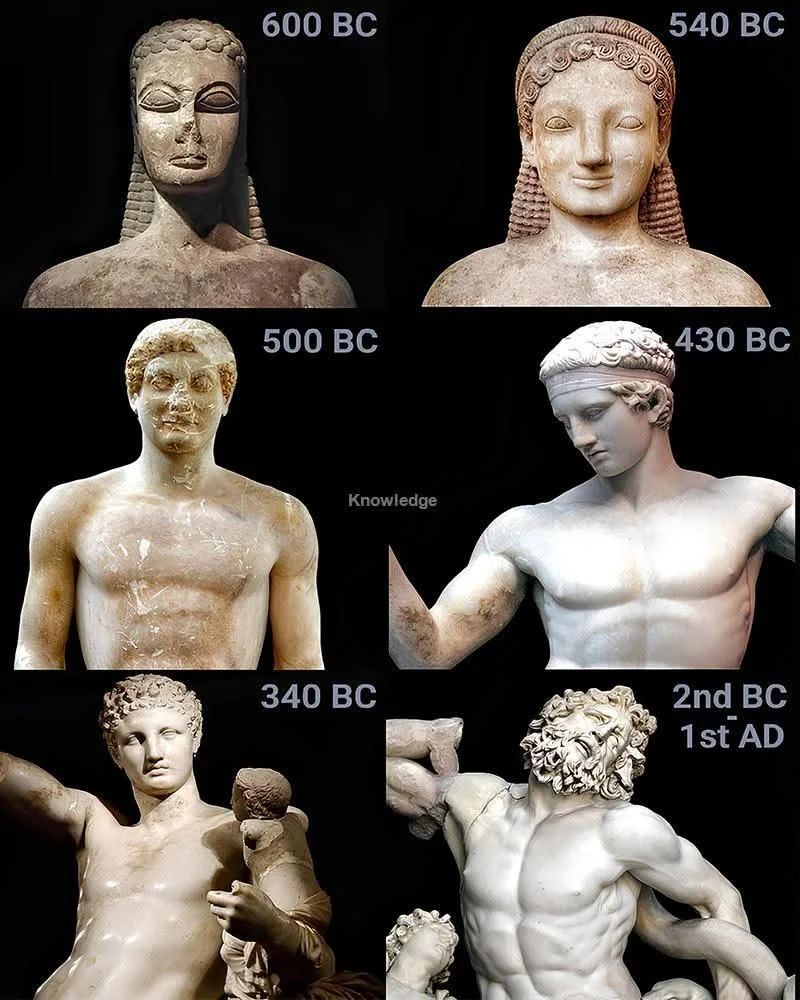

Greek sculpture from before 480 B.C. is crude in its representation of human anatomy, but still has the freshness and vigor of youth. Two examples of archaic sculpture were shown at the beginning of this chapter. These statues of nude youths (kouros) and draped maidens (kore) usually stand stiffly with clenched fists and with one foot thrust awkwardly forward--an obvious imitation of Egyptian statues. The fixed smile and formalized treatment of hair and drapery also reveal the sculptors' struggle to master their art. What made the Greeks different at this point was their willingness to experiment with new techniques. By contrast, the Egyptians were so bound by tradition that when Plato visited there, he noted that "no painter or artist is allowed to innovate on the traditional forms or invent new ones."

The mastery of technique around 480 B.C. ushered in the classical period of Greek sculpture whose "classic" principles of harmony, proportion and realism have shaped the course of Western art. Sculpture from this period displays an idealization of the human form, always a favorite subject of Greek art afterwards. The most famous sculptor from this time was Phidias, who carved both the relief sculptures on the outside of the Parthenon and the colossal ivory and gold statue of Athena on the inside.

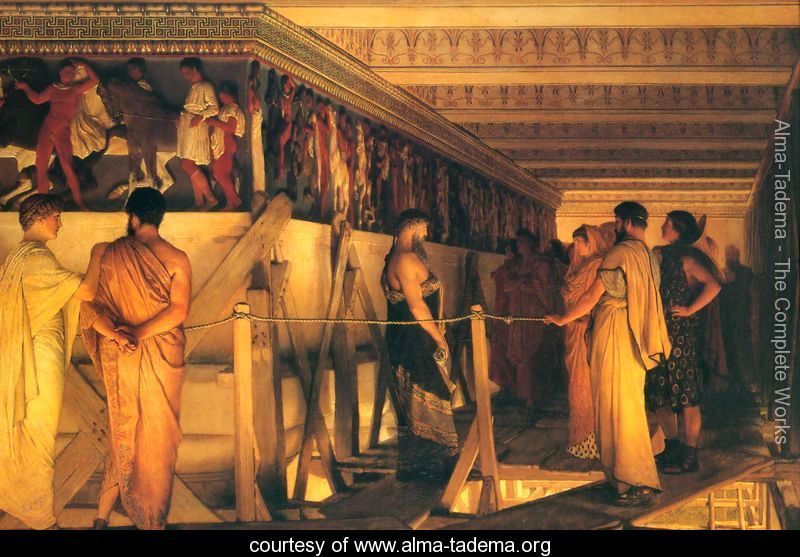

Today the relief sculptures on the Parthenon are plain white marble, but they were painted originally. Here Phidias is visited by some friends on the scaffolding, before the Parthenon is finished. This is not a photo using modern re-enactors, but an 1868 painting by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema.

The more relaxed character of fourth-century B.C. Hellenic sculpture, while still considered classical, lacks some of the grandeur and dignity that mark fifth-century art. Charm, grace, and individuality characterizes the work of Praxiteles, the most famous sculptor of this century. We can see these qualities in his supple statues of the god Hermes holding the young Dionysus and of Aphrodite stepping into her bath.(33)

Pottery, the oldest Greek art, followed crude imitations of Mycenaean forms at the beginning of the Greek Dark Age. Soon abstract geometric designs, sometimes with stick figures, replaced the Mycenaean motifs. With the arrival of the archaic period came paintings of scenes from mythology and daily life. From surviving Greek pottery and mosaics, we can get an idea of what Greek painting, now lost, was like.(34)

Athenian Society

For all the praises people give to Athenian democracy, it never involved more than 25,000 people. In fact, it would not have worked if it had many more participants than that, or if the Athenians weren't so civic-minded. We call our government a democracy, when it is really a republic; we send representatives to county seats, state capitals and Washington, D.C., rather than take part directly. The democracy of Athens has more in common with a New England town meeting than with the cautious debates and careful procedures that preoccupy Capitol Hill. Recently, some have suggested that the technology of the Internet has made it possible to bring back full participatory democracy; this author feels that, for better or for worse, our country will change beyond recognition if anyone tries it.

Most of the inhabitants of Athens were not even recognized as citizens. Women, slaves, and resident aliens were denied citizenship, could not vote, and had no voice in the government. Legally, women were first the property of their fathers, then of their husbands; they could not, as the law expressly stated, "make a contract about anything worth more than a bushel of barley."

Athens was definitely a man's world. Greece had plenty of goddesses, and celebrated the female form nearly as often as the male form in art, but the real status of women was low. Aristotle even argued that women provided only an abode for a child developing before birth, as male seed alone contained the full germ of the child. A wife's function was to bear children, make clothes and manage the home; she had to stay in the women's quarters when her husband entertained his friends.(35) Men did not marry until they were about thirty, and they usually married girls half their age. Marriages were normally arranged by the families, and prospective brides and bridegrooms seldom met before their betrothal. Daughters could not inherit their parents' property, so if there were no sons, a daughter could be forced to marry the closest male relative, to keep the fortune in the family. Families were often small, and infanticide, usually by exposure, of unwanted infants (especially girls), was practiced as a primitive form of birth control.

Most Greek families didn't want daughters because they were a financial burden on the family, especially when they got married. Every woman needed a dowry in the form of money, cloth, and weaving equipment. Plutarch tells us that Elpinice, the daughter of Miltiades, was the most desirable woman in Athens, but she married quite late, because Miltiades owed the state a large fine at the time of his death. The family was rich in land but didn't have enough money for a dowry. Her brother Cimon ended up auctioning her off; he gave her to the richest man in Athens when he agreed to pay off the family debt, making him the only groom in Athenian history who provided the dowry.

Greek society sanctioned double standards where sex was concerned, and the philandering of a husband did not cause unfavorable public comment. The raping of a free woman, though a crime, was a lesser offense than seducing her, since seduction meant winning her affections away from her husband. A peculiar institution, catering to the needs and desires of upper-class Athenian males, was that of high-class prostitutes called "companions" (hetaerae). These females were normally resident aliens and therefore not subject to the social restrictions imposed on Athenian women. A few of the hetaerae, such as Aspasia, the mistress of Pericles, were cultivated women who entertained at salons frequented by Athenian celebrities. However, champions of the social emancipation of Athenian women were rare, and the women themselves accepted their status. Apart from a few cases in which wives murdered their husbands (usually by poison), married life seems to have been stable and peaceful. Athenian gravestones in particular attest to the love spouses felt for one another. The tie to their children was strong, and the community expected sons and daughters to honor their parents.

Male homosexuality is frequently pictured in Greek art and mentioned in literature. The most common form was "boy love," a homosexual relationship between a mature man and a boy who was about twelve years old. The man became the boy's role-model and counselor, and might even help him choose a wife when he grew up. They viewed this relationship as a rite of initiation into adult society, and like other initiation rites, it contained a strong element of humiliation. Sparta strongly encouraged this pedophilia; other Greeks indulged to a lesser extent, because Greek men thought women were not intelligent enough to carry on a stimulating conversation.(36) Homosexuality between adult males, however, was only socially acceptable in the Theban army, where they reasoned that lovers would fight to the death to defend each other; elsewhere it was often outlawed, because it was "contrary to nature."

No ancient society did without slaves. In fifth-century Athens we estimate that between one fourth and one third of the people were slaves.(37) Some were war captives, others were children of slaves, but most came from outside Greece through slave dealers. No large slave gangs worked on plantations, as they did in Roman times and in the American South before the Civil War. Small landowners owned just a few slaves, who worked in the fields alongside their masters. Those who owned many slaves--one rich Athenian owned a thousand--hired them out to private individuals or to the state, where they worked beside Athenian citizens and received the same wages.(38)

Other slaves were taught a trade and set up in business. They were allowed to keep one sixth of their wages, and many of them could purchase their freedom. Although a few voices argued that slavery was an unnatural institution and that all people were equal (Euripides, for instance), the Greek world as a whole agreed with Aristotle that some people--especially non-Greeks--were incapable of full human reason; thus they were by nature slaves who needed the guidance of a master.

Slavery also helps explain why Greece was never interested in developing machinery. Abundant slave labor probably discouraged concern for more efficient production of food or manufactured goods. So did a sense that the true goals of humankind were artistic and political ones. One Greek scholar, for example, refused to write a handbook on engineering because "the work of an engineer and everything that ministers to the needs of life is ignoble and vulgar." An even more graphic example comes from Hero, a resident of Alexandria in the second century B.C. Hero invented a working steam turbine, but he couldn't think of a practical use for it! To him it was just a toy, and he ended up using it as an automatic door-opener for a temple, fooling superstitious pilgrims into thinking that the gods opened and closed the doors.(39)

Because of this outlook, classical Mediterranean civilization produced fewer inventions than contemporary societies like India and China. Population growth, also, was less substantial; it topped out when the Romans took over, and population actually shrank during the late Roman Empire period. A host of features of Greek life, including even its democracy, thus hinged on the slave system and its requirements.

Athenian Imperialism

A partial unity of Hellenic arms had made the victory over Persia possible, but that unity ended when the helot rebellion compelled Sparta to recall its troops and resume its policy of isolation. Because the Persians still ruled the Ionian cities and another invasion of Greece seemed probable, Athens in 478 B.C. invited all city-states on the Aegean to form a new defensive alliance, called the Delian League because its headquarters was on the island of Delos. At the founding ceremony, delegates sailed out to sea and threw large iron weights overboard, signifying that they intended their alliance to last until the iron floated up again.

From the beginning, Athens dominated the League. To maintain the navy that would police the seas, each city-state had to make a yearly contribution of either ships or money. Most of the 173 member states found it easier to give money, but Athens always gave ships. Because of that, the League's navy was almost entirely Athenian, and Athenian garrisons became a common sight around the Aegean.

By 468 B.C., the Ionian cities had been liberated and the Persian fleet destroyed, preventing Xerxes from coming back for a rematch. In 465 Cimon won the League's greatest victory; he liberated the provinces of Lycia and Caria in southwest Asia Minor and enrolled them in the League. Because of these successes, some League members thought the alliance was no longer necessary. One member, Naxos, refused to contribute anything for the League in 468, and the Athenian navy attacked and looted that island. In 465 Thasos tried to drop out, and Athens again sent its ships; they took the island by storm and forced Thasos to tear down its walls, surrender its fleet, and become an Athenian vassal. These actions showed that the Athenians wouldn't let anyone quit the League, because of their fear of the Persians and because they needed to maintain and protect the large free-trade area so necessary for Greek (and especially Athenian) trade and industry. They also felt that any state which benefitted from the League ought to belong to it; when the city of Carystus, on the island of Euboea, refused to join, Athens attacked and forced it into the League.

Gradually, Athenian domination of the League became Athenian rulership over all the states in it. Soon members were ranked in three categories, which were, from top to bottom: Athens, other members who contributed ships (Chios, Lesbos and Samos), and everybody else. Minor members might be forced to donate soldiers as well as money, and Athenian officials might come to manage their affairs. Athens insisted on the right to try criminals accused of conspiracy or treason, since these crimes threatened the safety of the League, and eventually it extended its jurisdiction to all legal cases between League members. In 454, Pericles was concerned that the League treasury was not safe from thieves, so he moved it from Delos to Athens. Not long after that, the Athenian coinage and system of weights and measures was made the official one among all league members. Now Athens regarded the other League members as satellites, so the League quietly turned into an Athenian empire, with a population of two million. By suppressing local aristocratic factions within its subject states, and by clearing the Aegean of pirates, Athens both eased the task of controlling its empire and emerged as the leader of a union of democratic states.

To many Greeks, Athens was now a "tyrant city" and an "enslaver of Greek liberties." Pericles, on the other hand, justified Athenian imperialism on the ground that it brought "freedom" from fear and want to the Greek world:

"We secure our friends not by accepting favors but by doing them . . . We are alone among mankind in doing men benefits, not on calculations of self-interest, but in the fearless confidence of freedom. In a word I claim that our city as a whole is an education to Hellas."(40)

Athenian-Spartan Rivalry

Like the protagonist in one of Sophocles' plays, Athens expressed too much pride, and this led to her downfall. For a while after forming their empire, the Athenians felt they were unbeatable. Their ships made them master of the eastern Mediterranean, and Athenian merchants prospered everywhere, providing the resources to wage war on an extensive scale. In 459 Megara, a former ally of Sparta, asked to join the empire, and in the same year Athens dispatched soldiers to aid Inaros, an Egyptian who led a long rebellion against Persia. After a two-year war (458-456) the Athenians captured Aegina, an ally of Corinth, and dragooned it into the empire.

These activities alarmed Sparta and Corinth, who would have let Athens do its own thing had it been willing to let them do theirs. The result was the First Peloponnesian War. Sparta moved its army into Boeotia in 457, and won a victory at Tanagra, but in the same year the Athenians defeated the Thebans at Oenophyta; this brought all of Boeotia except Thebes under Athenian control. Both sides agreed to a five-year truce in 451, but when it ended, Boeotia revolted; this encouraged Euboea and Megara to revolt and tipped the balance in favor of Sparta and its allies. A Spartan king marched on Athens, but withdrew inexplicably before he encountered Pericles' forces (the king went into self-imposed exile afterwards). Then Athens recovered Euboea, but her land empire was now gone, so she signed a new truce in 445 and wisely abandoned the ambitions which had started the fight.

The truce allowed Athens to keep a sea empire and Sparta a land empire, and was supposed to last for thirty years. It only lasted for fourteen, though. Athens looked overseas, to the rich trade routes of Sicily and southern Italy, and her moves to take over this commerce antagonized the city that dominated this area, Corinth. In 433 Athens formed an alliance with Corcyra (modern Corfu), an island colonized by Corinth but now at odds with the mother city. Meanwhile Potidaea, a Corinthian settlement in northern Greece which had passed into the Athenian Empire, revolted, and Athens sent ships to put down the rebellion. Corinth objected to both these actions and warned Athens to stop. Feeling that war was inevitable, Pericles retaliated by putting a total embargo on trade with Megara, the nearest city-state not under Athenian control.

This is the end of Part II. Click here to go to Part III.

FOOTNOTES

21. C. E. Robinson, Hellas: A Short History of Ancient Greece (Boston: Beacon Press, 1955), p. 68.

22. All the Spartans could do was protest when Themistocles rebuilt the walls of Athens, something they didn't want. In 470 Elis and Arcadia left the Peloponnesian League, and Elis established an Athenian-style democracy. They came back when the helot revolt threatened them all.

23. It took until 455, though, and the Athenians ended up finding a new home for the helots in the city-state of Aetolia.

24. Admirers called Pericles "the Olympian" because his wisdom and eloquence reminded them of the gods. However, an accident at birth left him with a pointed head, so opponents gave him names like "onion-head." That is why artists always portrayed him wearing a helmet.

25. Thucydides, II, 65.

26. Ibid, II, 37 and 40.

27. M. Cary and T. J. Haarhoff, Life and Thought in the Greek and Roman World, p.192.

28. A. R. Burn, The Pelican History of Greece, p. 272.

29. A. R. Burn, The Lyric Age of Greece (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1960), p. 166.

30. Ibid, p. 236.

31. Aeschylus, Agamemnon, from Ten Greek Plays, trans. Gilbert Murray and ed. Lane Cooper (New York: Oxford University Press, 1929), p. 96.

32. Medea, trans. Gilbert Murray, Ten Greek Plays, pgs. 320, 321.

33. His sculpture of Aphrodite was so attractive that Greeks claimed the goddess saw it and exclaimed, "Alas, when did Praxiteles see me naked?"

34. Like their modern-day counterparts, Greek artists often signed their works. One Athenian potter added a jab at a rival by writing on his pots, "As Euphronios never, ever could."

35. Socrates spent most of his time away from home, teaching in public places, because it got him away from his wife Xantippe's sharp tongue.

36. When Spartan soldiers came to town you didn't hide the women, you hid the boys!

For today's weddings we spare no expense to make the bride look like a princess; the Spartans, by contrast, humiliated their brides. After the wedding ceremony, a Spartan bride's hair was cut short, she was dressed in men's clothing, and she had to lie on a pallet in a darkened room, waiting for the groom to come to her. They didn't have romantic honeymoons, either. If the groom was on active duty, he would take the bride back to her parents the next day, and then return to the barracks. A few years ago it was suggested that the Spartans did all this to ease the groom's transition from a homosexual to a heterosexual lifestyle. Supposedly, because Spartan men had only been around other men for most of their lives, they knew less about women than a modern-day high school nerd does, and might not have even wanted female companionship, so they had to be coaxed into it by making the bride look like a boy!

37. Sparta had a higher percentage of slaves; helots outnumbered "Spartiates" (full citizens) by about 10 to 1 at this stage.

38. Because it was considered unseemly for Athenians to lay hands on each other, the city employed foreign slaves as policemen. Among these slaves were 300 that were called "Scythian archers"; however, they were armed with nonlethal whips instead of bows, and they weren't always ethnic Scythians, the fierce nomads of the Russian steppe. These folks were busiest on days when the democracy didn't have a quorum attending the civic meetings; when that happened, the "Scythians" would lasso and bring in more citizens, using ropes dipped in red paint. To show up for jury duty or some other function wearing a "slave's stripe" was embarrassing, to say the least.

39. Hero also built the first vending machine, an urn that dispensed a cup of water when a coin was dropped in the slot on top of it; this went into the temple, too. It may be just as well that Hero's inventions didn't catch on; if they had, the industrial revolution might have begun 2,000 years earlier than it actually did, and a nuclear war might have destroyed the Roman Empire.

40. Thucydides, II, 40-41.

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A History of Europe

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|