| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

A Concise History of China

Chapter 2: The Development of Chinese Civilization

Before 255 B.C.

This chapter covers the following topics:

Mythical and Legendary Times

Chinese mythology teaches that the first man who ever lived was a hairy giant named Pangu. Although he resembled a cave man, Pangu was a superhuman being who hatched from a primordial egg and created the world. Using an axe, hammer and chisel, he separated Yin and Yang, the negative and positive forces that everything else is made from; Yin became the earth and Yang became the sky. As he worked on shaping the earth he grew, until he could raise the sky above the earth when he was finished. Then Pangu died, but his death completed his work. His head, hands, feet and belly became the five sacred mountains of China; his breath became the winds and clouds; his hair became the trees; his voice became the thunder; his blood became the rivers; his flesh became the soil; and his bones became the rocks, minerals, and precious stones in the earth.

After Pangu the Chinese myths list three families of semi-divine brothers who ruled as kings for a period of two million years: the 12 Heaven Kings, the 11 Earth Kings, and the 9 Man Kings. Then around 2852 B.C. came the first of ten fully human kings with larger-than-life achievements.

The ancestors of the Chinese were a tribe we now call the Sino-Tibetans, who migrated from the neighborhood of Lake Balkhash, in Central Asia, at an uncertain early date. They probably traveled through the gap between the Tien Shan and Altai mts., skirting the Gobi Desert on its southern fringe, to reach the North China plain. Part of the tribe, what anthropologists call the Tibeto-Burmans, split off to head south and southwest; they became the ancestors of the Tibetans, Burmese, and various ethnic minorities in what is now southern China and Southeast Asia. Those who stayed in northern China settled in a small basin, right at the junction of the Wei and Yellow Rivers, in modern Shaanxi province. This was an oasis surrounded by discouraging terrain on all four sides: to the north was the windswept Ordos plateau, and beyond it the Gobi Desert; in the west, semiarid highlands, leading to Tibet; to the south, forests and another mountain range; in the east, swampy lowlands. All of these frontier regions were inhabited by wild men, non-Chinese barbarians who sometimes raided the Chinese for food and anything else worth taking, until the Chinese became strong enough to drive them out. The rivers of the basin offered such good fishing that several generations went by before the ancestral Chinese felt the need to supplement what they could catch by growing food.

Plenty of food allowed large families, giving the Chinese the advantage of numbers against everyone else. By the beginning of the Xia dynasty (see below), there may have been as many as one million people living in the Yellow River valley. This figure included both Chinese and non-Chinese, and in the outside world, the Nile and Indus river valleys probably supported larger populations at this time, because both were intensely irrigated. But in the long run, the Chinese would grow steadily, with few interruptions. At some point in the first millennium B.C., China's population caught up with that of other nations, and the strength of numbers has been a characteristic of Chinese civilization ever since.

The first three kings--Fuxi, Shennong, and Huangdi--are called the inventors of Chinese civilization. It appears that like in some other legends, time has lumped together the activities of many people so that only a few get credit for them all. Fuxi may have been the original leader of the Sino-Tibetan peoples when they migrated out of the deserts and mountains of Central Asia. He was a shepherd, who is credited with teaching the Chinese how to domesticate animals like sheep, pigs, dogs, horses, and poultry. He also taught them how to fish, how to build houses of mud and wood, how to marry and raise families, how to make musical instruments, and invented a form of divination called I Ching (supposedly he got this idea when he noticed a set of markings on the shell of a turtle and concluded they were magical symbols). Finally he is called the inventor of writing, but this is doubtful, for no example of it turns up before the Shang dynasty, as noted below. Fuxi's wife, Nuwa, is either credited with creating the first ordinary humans out of clay, or is seen as the mother of the human race; it depends on which myths you are reading.

Shennong, the next legendary king, is called "the divine farmer" because he taught the people agriculture: how to plow the ground and plant grain in it, how to cultivate and harvest crops. The people now spread out to settle several villages across the middle portion of the Yellow River valley. Another legend credits the discovery of acupuncture around this time, when a soldier (presumably fighting barbarians) got hit by an arrow; the legend doesn't say what part of him was struck, simply that he became numb in a completely different part of his body.

Since the country was now so big that no leader could personally oversee the people from one spot, the next king, Huangdi, introduced organized government, religion and law. He united the Yellow River communities into one state, built roads to join the different villages, set up markets and fairs to promote commerce, defined a system of weights and measures by law, and is credited with inventing pottery, copper smelting (doubtful, see footnote #2), and money. Finally, he had astronomers develop the first calendar, and established the annual sacrifice that kings performed on the first day of winter for centuries to come. His wife, Leizi, gets the credit for discovering silk and how to produce it. Huangdi means "Yellow Emperor" or "August Emperor," and this king was rated so highly that no Chinese monarch would use his name again for 2,400 years.

After Huangdi came seven more monarchs. Not much was recorded for three of them, and the fourth was a weak ruler, but the last three--Yao, Shun and Yu--were so outstanding that they have been called the best Chinese rulers who ever lived. For example, Yao greatly extended and strengthened the realm and established fairs and markets over the land. Under him the crime rate was zero; Confucius describes his reign as a time when "the house door could safely be left open."

Up to this point the Chinese state was not a hereditary monarchy, and each king picked the best man in the kingdom to succeed him. However, Yu couldn't find a better man for the job than his own son. Thus Yu became the founder of the Xia dynasty (traditional dates 2205-1766 B.C.).(1)

Up to now no archeological evidence has been found to indicate that any of the kings preceding the Xia dynasty actually existed. With the Xia dynasty the archeological picture begins to become clear. Three neolithic cultures, called the Yangshao, Dawenkou, and Longshan cultures, have been discovered in the Yellow River valley, in the provinces of Shaanxi, Shandong, and Henan respectively. Here we find primitive but well-ordered communities of up to 600 people that used polished stone tools and black pottery. They had no writing--unlike Middle Eastern and Indian communities from the same time--and lived in villages surrounded by immense walls of stamped earth, a clear sign of large-scale, if low-tech, organization. The leaders of the villages had big houses made of wood and thatch, meaning that power (and wealth) was already being concentrated into the hands of a few. The Xia kings imposed their will on their subjects and "barbarian" neighbors through a combination of armed might and ceremonial terror; the latter involved a cult of human sacrifice. At Erlitou, skeletons were discovered with their hands tied and heads missing.

The first Chinese lived by growing millet, various native fruits, vegetables and nuts; they also raised livestock (mostly dogs and pigs, but cattle, sheep, goats and chickens were also known to them). They traded with their non-Chinese neighbors, especially the rice-growing peoples that lived to the south.(2) The Chinese already knew how to carve jade at this early age, and clay silkworms and spindles exist as evidence that they knew how to make silk as well; these secrets would be the source of great wealth for China in the future.

Of these villages, the Longshan ones were the youngest, and all probably existed in the third millennium B.C. It is now thought that Erlitou, the largest settlement of the Longshan culture, was the capital of the Xia dynasty, but we have no written records to tell us for sure.

After the great Yu, 16 kings from his family ruled for a period of 439 years. Though some of these were able rulers, none of them were as good as the dynasty's founder. The third king, Tai Kang, went on a three-month hunting trip, prompting his brother Zhong Kang to throw him out. A few years later, an eclipse of the sun took place without warning, and Zhong Kang put to death the two court astronomers for failing to predict it.(3)

Finally there arose a king named Jie, who reportedly was so cruel and depraved that nobody could stand him. A competent provincial governor named Tang raised the standard of revolt, and people from all over the land joined him. Soon Jie Gui was forced to flee into exile, and a new dynasty took over.

It was during the next age that China evolved from a primitive agricultural society into an elaborate civilization. Tools made of bronze first appeared in the closing days of the Xia dynasty; under the Shang techniques for casting intricate bronze vessels and works of art were developed. In Xia times the king ran the government almost single-handedly, performing the most important sacrifices and traveling around the kingdom every year to make sure that everything was all right. This worked well when the kingdom consisted of little more than today's Henan province, but under the Shang both the country and the government grew too large for one man to directly supervise everything. A civil service was set up in the capital to handle everyday matters; this was the forerunner of the huge bureaucracy that would characterize later eras. And now the Chinese were spreading out of the lower Yellow River valley to settle new lands in the east, south and west; to govern the more distant regions, history's first example of feudalism appears to have been used, but we don't have records on how it worked until the Zhou dynasty.(4)

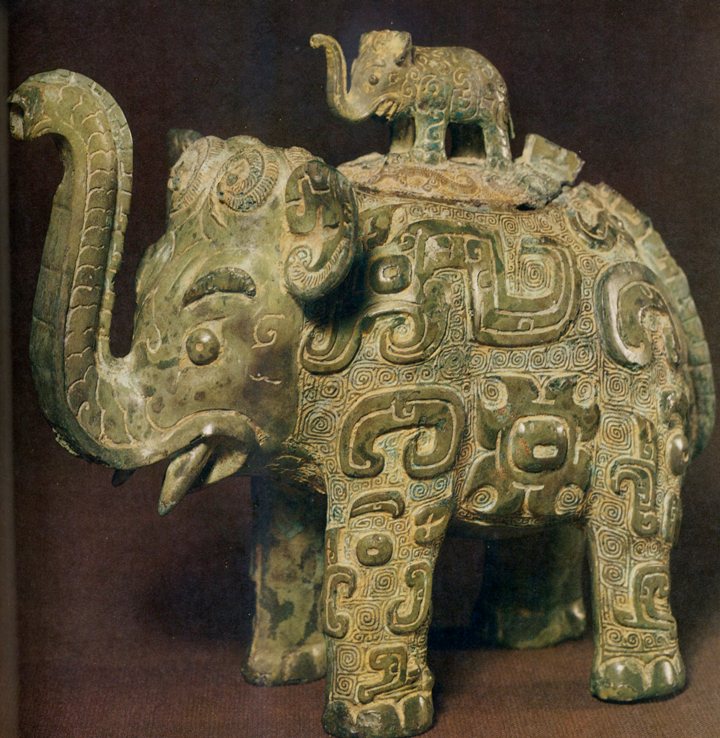

Two excellent example of Shang dynasty bronzeware, ritual vessels shaped like a tripod (called a jue) and an elephant. These held food and wine, and were the most important items used in ancestor worship ceremonies.

The Shang were very aggressive rulers and almost constantly at war with the non-Chinese tribes around them, which they called the fang. Known to their weaker neighbors as "the great terror," they seemed to enjoy warfare both for sport and for the loot that victory brought. The king probably kept only a small standing army at home, but on short notice he could call up bodies of troops ranging from raiding parties of 1,000 to grand expeditionary forces of 30,000 men. The officers rode in handsome bronze and turquoise chariots, which may have been introduced from the barbarians of Asia's interior.(5) In one extraordinary story, it is said that Fu Hao, the favorite concubine of a king named Wu Ding (1324-1265), led the armies against a western tribe, the Qiang Fang. Another record tells of Di Xin, the last Shang monarch, using elephants in a three-year war that overcame the barbarians of western Shandong.

Another aspect of Chinese life that developed in this age was religion. A class of priests arose to relieve the king of the duty of making offerings to the gods every day. In addition, the simple nature worship of earlier days was combined with a worship of ancestors, because the Chinese have always considered family life to be very important. Most of the gods in Chinese mythology were really ancestors who had been deified for some important accomplishment. It was believed that these ancestors were still interested in family affairs, so their descendants made regular visits to the graves to tell them important news from home; they also occasionally left meals as a sacrifice to keep the spirits from going hungry.

When a person wanted the ancestral spirits to answer a question, he used a form of divination: "oracle bones." The question would be written on a bone in both a positive and negative fashion, like "Is Father Yi harming the king?" and "Is Father Yi not harming the king?" Large, flat bones like turtle shells and the shoulder blades of oxen were used most of the time, because these provided more space for writing. Then a priest would make a hole in a bone, stick in a red-hot piece of metal to make it crack, and interpret the answer to the question from the shape of the cracks. Afterwards they would also write the following on the bone: the answer divined, the name of the priest, and whether or not the answer turned out to be correct (evidently they saw it as a process of trial and error). A lot of oracle bones asked whether the king should perform rituals, telling us that at this stage of Chinese civilization, the main concern of the king and the priests was to make sure all rituals were done right. This is the oldest form of Chinese writing ever found.(6)

We know the Shang dynasty actually existed because the names of several Shang kings are on the oracle bones. The oldest king whose name we recognize is the previously mentioned Wu Ding, so here is documentary evidence for the dynasty's last two hundred years. We also get a glimpse of Shang-era politics in the oracle bones, because many of the questions had to do with enemy states. From this we learn that the number of fang varied; the greatest number mentioned in any time period was thirty-three. Of all the neighbors, the Kung Fang and the Tu Fang got their names on the oracle bones most frequently.

Ancestor worship had its violent aspects as well; at a royal funeral dozens of captives were beheaded and buried with the king, so that they could be his guards and servants in the afterlife. And sometimes, if a priest made dances and prayers for rain and got no results, the people would conclude that the ancestral spirits wanted more than that and make a burnt offering of the priest! The practices of oracle bones and human sacrifice went on for centuries after the Shang era ended, at least until the fourth century B.C.; maybe the Chinese were not willing to change their rituals until the philosophers of that time questioned whether they should be performed.(7)

After 1200 B.C., the house of Zhou, the rulers of the westernmost province (the Wei River valley in modern Shaanxi), grew to become the most powerful nobles in the kingdom. Oracle bones often mention the Zhou, sometimes as friendly tribute-payers and hostile at other times. Marriages were frequent between the Shang and Zhou families. The most successful Zhou governor, Wen Wang, is described as virtuous and intelligent; he continued to recognize the superiority of the Shang out of feudal loyalty, but expansion into barbarian-held territories north and south of the Zhou realm made him at least as powerful as the Shang monarchs themselves.

The end of the Shang dynasty echoes the Xia; poor kings followed good ones, until the totally extravagant and cruel Di Xin sat on the throne. According to the records (political propaganda?) of later scholars, Di Xin raised taxes and dissipated the national treasury on wine-soaked orgies; he also delighted in inventing new kinds of torture, like making victims walk on a greased pole over a pit of burning coals and waiting for them to fall to their deaths. The country entered such a state of lawlessness and immorality that the Mandate of Heaven passed to Wen Wang. Wen refused to rebel against his lord, but his son Wu Wang raised the banner of revolution. Many Shang warriors disliked the king so much that they readily switched sides. Di Xin immolated himself in his palace, and Wu Wang moved the capital to Hao, a site about on the Yellow River about halfway between Anyang and the original Zhou capital.(8) Wu Wang died not long after that, and his brother Zhou Gong ruled as regent for the Wu's son, Cheng Wang. Zhou Gong spent three years consolidating the kingdom, putting down a rebellion by Di Xin's son, subjugating more eastern tribes, and establishing Zhou supremacy everywhere. Thus Cheng Wang inherited a large, peaceful realm, now ruled by the longest-lived dynasty in Chinese history.

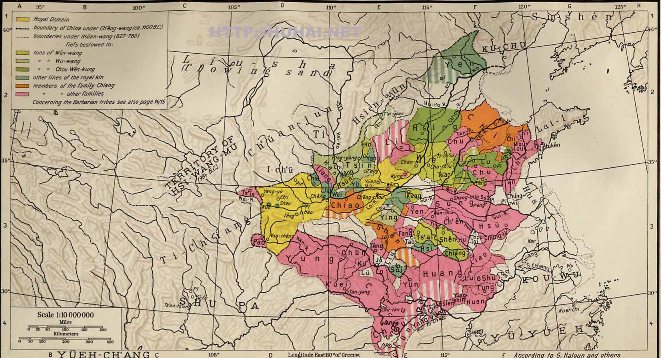

In the days of the Zhou dynasty the last mists concealing the difference between legend and true history dissipate, and we find the Chinese spreading out in every direction. Whereas the kingdom of the Shang dynasty was mostly confined between the Yellow and Yangtze rivers, by the end of the Zhou dynasty there were Chinese-settled areas stretching east to the Pacific, south of the Yangtze as far as Hunan(9), as far west as the land could be cultivated (Gansu & Sichuan), and north to the borders of Mongolia and Manchuria. In every direction there were still barbarians to deal with, but these were rarely a match for the more numerous, better organized and better equipped Chinese, who either assimilated them or drove them out, depending on what mood they were in. Only the barbarians in the north were a serious threat; this group, called the Xiongnu by the Chinese, and the Huns by Europeans later on, was especially fierce, and their warriors, all of them archers on horseback, were faster than their Chinese opponents. In this age walls were built along several parts of the northern frontier to keep the Xiongnu out, the first segments of what would become the Great Wall of China in the next age.

To administer this large and well-populated area, Wu Wang resorted to the same solution as his Shang predecessors: feudalism. The kingdom was divided into smaller territories called fiefs, to be administered by nobles loyal to the new order. To start with, surviving members of the Shang family and their servants were allowed to administer a fief in the southeast; they just had to acknowledge that they were now part of a larger state, and the Zhou were their lords. That fief was part of modern-day Anhui province, and if you go to Anhui you may meet people who claim to be descended from the Shang. For themselves, the Zhou kings kept a two-piece royal domain: the western domain in Shaanxi that they ruled before the revolution, and a smaller area in Henan. The rest of the kingdom was given to various relatives and officers; whoever was in charge had the responsibility of collecting taxes and defending his realm from outside attacks.

The lifestyle in those days was one of extreme contrasts; there was no middle class at first, just the peasantry and the nobility, with a great gulf between them. The nobility always knew that their wealth depended on the hard labor of the peasants, but that did not make them feel that the peasants had any rights. First of all, the peasant had to make ends meet when his crops were taxed; sometimes he was even taxed for the fish he caught in a lake! In addition to all the calamities of nature, his crops were in danger of being irresponsibly trampled down by any noble hunting or going to a battle. Wars were not common in the early years of the dynasty, but when they happened the sons of a farmer could be drafted to build roads or serve as foot soldiers, with little guarantee that they would ever see home again even if they survived. Even the daughters were not safe; a girl-watching noble could make a concubine of any pretty face that caught his eye. About the only thing that made the peasant's life easier was the invention of new tools, like the iron plow (iron was discovered and first used by the Chinese around 500 B.C.).

Feudalism is an efficient system of government when the king is strong, the nobles are loyal, and communications are reliable. When this is not the case it is a good formula for lawlessness. The lords of each fief were expected to show their loyalty by making annual visits to the king; when the king was weak or unpopular the lords would stay home, and the worst kings did not even care whether the lords came or not. Lasting more than eight hundred years, the Zhou dynasty was the longest-lived of all Chinese dynasties, but once feudalism was fully implemented, the Zhou kings were no longer strong rulers. The first half of the dynasty (1122-770 B.C., often called the "Western Zhou" period by modern historians) was a period of decentralization, when the kings lost most of their power, and the lords around them not only acquired domains bigger and stronger than the Zhou royal domain, but also ruled them as kings in everything but name (the names would come in the next period).

Often the Western Zhou rulers were not able to handle the responsibilities left to them. One spent most of his time exploring the lands beyond the frontiers of his kingdom, looking for the magical places where gods, dragons and spirits lived. Another, Li Wang, was so cruel that the nobles got together and deposed him in 841 B.C.; two of them ruled until the crown prince, grew up. This crown prince, Xuan Wang, won more than one war against the barbarians after he became king (827-782 B.C.), but he was succeeded by the last Western Zhou king, Yu Wang.

In 780 B.C., a major earthquake struck, and a soothsayer named Bo Yangfu called it an omen, a sign that the Zhou dynasty was about to fall. This was followed by an eclipse in 776 B.C. But just in case anything else was needed, there was Yu Wang's behavior; he lost whatever respect the nobles might have had for him, by pulling a royal prank. He had a beautiful but unhappy concubine named Baosi, who hardly ever smiled; she gave him a son named Bofu. Enraptured by her looks, Yu Wang divorced Shen, the rightful queen, sent her and the crown prince away, married Baosi, and made Bofu the new crown prince; all this was a violation of custom and a guaranteed offense against the in-laws! Then he tried everything he could think of to make his new wife laugh. When none of the usual jugglers, acrobats, and court jesters could cheer her up, Yu Wang ordered the burning of bonfires outside the city. In those days bonfires were used as warning beacons, to quickly alert the countryside of a crisis in the capital. When the nearest lords saw the bonfires, they mobilized their troops and alerted the lords that were farther away. Soon the entire army was converging on Hao, expecting to find barbarians attacking the city, but when they got there they found no crisis at all. The sight of all those soldiers looking very silly because they had come for nothing caused Baosi to clap her hands and burst into laughter; Yu Wang was pleased that his trick had worked, but the soldiers went home very angry. Not long after that the father of the previous queen revolted, and he called in the Xiongnu as allies. When he heard about the danger, Yu Wang again ordered the lighting of the beacon fires, but just as in the story of the boy who cried "Wolf!," nobody came this time. The loyal nobles chose to stay home rather than be summoned for the whims of a woman; the capital was taken, Yu Wang and Bofu were killed, and the concubine was led into captivity.

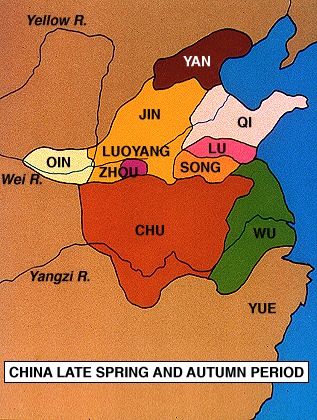

The next king, Ping Wang, fled from the ruined city of Hao to a more centrally located and better protected city, Luoyang. It was also east of Hao, so we call the second half of the Zhou dynasty the Eastern Zhou period. The leader of Qin, a non-Chinese tribe, provided the guards to escort the king to the new capital, and Ping Wang rewarded the Qin by letting them have part of the Zhou royal domain in the west, since he could no longer administer it directly. This move elevated the Qin's status from that of friendly barbarians to serious contenders for supremacy over all of China. What remained of the royal domain was now surrounded by other Chinese states, and the kings after Ping Wang found that they could no longer enlarge that domain, because that would mean trampling on the rights of loyal vassals.

Whereas the king's influence was limited during the Western Zhou period, during the Eastern Zhou period his power disappeared completely. Reduced to a figurehead, the king found that the only job left for him was the series of archaic religious duties he continued to perform. Thus, when the aggressive lords of Qin deposed the last Zhou monarch in 255 B.C., it made little difference to the rest of the country. We call the first 289 years of the Eastern Zhou period (770-481 B.C.) the "Spring & Autumn Era," after a contemporary book covering the politics and history of that time. During this period the rulers of the states stopped looking to the king for authority; in fact, as early as 750 B.C. the ruler of a powerful southern state, Chu, started calling himself king, as if the wild men on the frontier had replaced the Zhou as the real rulers of China.(10)

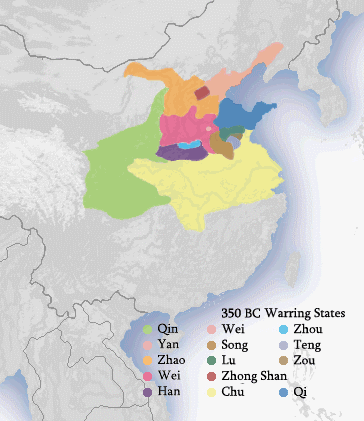

In the Spring & Autumn Era, we know for sure that 148 states existed, and there could have been as many as 250. Simple math shows that 170 states can form 10,878 ((148*147)/2) possible combinations of two-state alliances; what an opportunity for intrigue and conflict! The most successful states were those on the periphery of China; these states could enlarge themselves by taking barbarian-held lands without drawing protests from other Chinese states. Equally important, the frontier states were less conservative than the rest, and more willing to experiment with new ideas. As a result, the three most important states to rise up with the dissolution of the Zhou dynasty were all on the frontier: Qi in the east (Shandong), Chu in the south (Hubei and Hunan), and Qin in the west (Shaanxi).

In the early seventh century, Qi was China's most advanced power. Because it was on the shore of the Yellow sea, it was a major producer of salt, and it had rich reserves of iron. It also had a farsighted ruler who realized that centralized government, with a uniform system of taxation and military conscription, was more efficient than feudalism. His name was Huan Gong (or Duke Huan, to borrow a Western title of nobility), and he had an equally talented advisor, Guanzi. Around 680 B.C., the state of Chu went on the warpath against its smaller neighbors, and Duke Huan was so widely respected that the Zhou king gave him permission to assemble a league of anti-Chu states with the duke in charge of it. He remained hegemon, or overlord of the league, for thirty years, and in 656 B.C. they compelled Chu to sign a peace treaty and send regular tribute to the Zhou court. But it was only a lull in the storm; more wars would break out in the next century and more hegemons would rise up to end them; in the end nobody could achieve lasting peace.(11)

The next duke whose adventures have come down to us was Mu Gong of Qin (659-620). Early in his career the heir of Qin's nearest rival, Jin (a large state in Shanxi province), was driven out by enemies and fled to Qin for protection; he promised Mu Gong eight cities if Qin would help him get his state back. The duke was delighted and sent an army strong enough to do the job, but afterwards he never heard anything more about the eight cities. Shortly after this, a famine broke out in Jin, and its duke called on Mu Gong again for help. Mu Gong consulted with his ministers. The first one said attack Jin while it is weak; the other two said send food, so the duke of Jin will be in his debt twice, and Heaven (and the people of both states) will favor the fortunes of Qin. He acted on the majority and sent a vast wagon train of food to the capital of Jin. The next year it was Qin that suffered from a bad harvest, and the hardhearted ruler of Jin refused to send even a single wagon of grain. This was too much for Mu Gong; when his state recovered, he made war on Jin, and as his ministers foretold, defeated it easily and took all of its territory on the west bank of the Yellow River.

At other times he was not so wise. The little state of Zheng, about three hundred miles to the east, once asked him for military assistance, and the Qin troops did such a good job that the duke of Zheng asked if he could keep three Qin generals to train his army. A few months later one of the visiting generals was put in charge of the northern gate of Zheng's capital, and he sent Mu Gong a letter suggesting that if Qin secretly sent an army, it could sneak through that gate and capture the city. This time the ministers advised against attacking someone so far away, but the duke decided to try it anyway. The path from Qin to Zheng passed through the Zhou royal domain, and protocol dictated that they stop there, bow before the king and tell him what they were about to do. But knowing that Qin was stronger than Zhou, the army did not take the trouble to do this; instead of stopping, the officers dismounted when they got within sight of Luoyang, and walked on foot past the walls of the Zhou capital with their helmets in their hands as a sign of respect; then they leaped back into their chariots and marched away quickly.

Upon entering Zheng the army of Qin met a very clever old man who probably saved his state from destruction. He was driving a dozen oxen to sell in the marketplace, and like everyone in Zheng, did not know that a hostile Qin force was approaching. Nevertheless, when he saw the mighty host, he suspected that it was not on a friendly mission and went to the generals, presented the oxen as a gift to the soldiers, and told them that the duke of Zheng was preparing more food and resting places for his guests in the city. The generals stopped and thought about this. If the duke of Zheng knew they were coming, there was no point in going any farther; surely he was no longer leaving his gates in the care of a foreigner! They turned back, while the old man with the oxen hurried to tell his lord what had happened. Not wanting to come back empty handed, the army of Qin passed through Jin on the way home, and captured a city. Jin responded with an ambush in a mountain pass that killed or captured every soldier in the Qin army. Duke Mu did not forgive or forget this defeat, and a year later he sent a better army to avenge the first one, defeating Jin soundly a second time.

One more story about Mu Gong deserves to be told, because it could have happened only in China. North of Qin was a tribe of barbarians that gave him a lot of trouble, so he sent spies to find the source of their strength. It turned out that a Chinese scholar was living in the barbarian camp. We don't know why he went there; no Chinese in those days would willingly leave the Middle Kingdom, so he probably was either an exile or disgusted with life in his home state; at any rate he had become the local chief's most trusted advisor. He was making that tribe more powerful by bringing it unity and order, and Mu Gong rightly saw this as a threat. He asked his ministers what to do, and one of them suggested a way of corrupting the barbarian chief. Since this chief had never heard the beautiful music of the Middle Kingdom, let the duke send musicians to lull him into a life of ease and pleasure, all the while making sure that the Chinese advisor was not there to exert a positive influence. The duke agreed it was worth a try and pretended to be friendly to the barbarians; he sent the chief two of his best bands of musicians, and invited the scholar to visit his state and see for himself how different life was in Qin from the rest of China.

The plan couldn't have worked better. When the scholar arrived he was given a seat of honor next to the duke, offered food from the same bowls Mu Gong used, and asked for his advice on many things. Meanwhile in the Gobi Desert, the musicians knew just what songs would best control their host and played them until the chief no longer wanted to do anything but lie in his big tent and listen to them all day long. Without the chief ruling, or the scholar advising, the tribe became lawless and quarrelsome. When the scholar returned to the barbarians after a prolonged stay in Qin, he saw how lazy his employer had become and promptly quit; then he went back to Qin and offered his services. Mu Gong hired him at once and learned from him all he could about that tribe of barbarians. A year later he attacked them, defeated them easily, and conquered their territory.

Despite the numerous petty wars between the states, good manners counted--at first. The lords followed an elaborate code of chivalry; rituals and courtesies preceded a battle, defeated opponents were treated honorably, nobles were rarely killed in battle (unfortunately this did not apply to the drafted peasants), and defeated states may lose a few cities but were never conquered completely.

For example, in 638 B.C. Xiang Gong, the duke of Song, refused to attack an army of Chu while it crossed a river; he thought that would be unsporting.(12) In 594 B.C. the king of Chu, while besieging a city, sent his war minister to peek at the enemy. On top of the city wall he met a minister from the other side, who told him they were starving. Since the army of Chu was hungry too, it went home! (Maybe they concluded there was nothing left worth having in the city.)

The Age of Warring States Begins

Every year different alliances arose, usually led by one of the stronger states, only to be dissolved by the breaking of a treaty, a change in the balance of power, or the death of one of the lords involved. Whenever one state became too strong, the others would join together and cut it down to size; often this meant Qin & the little states vs. Chu, or Chu & the little states vs. Qin. At first warfare was carried on in the same manner as it had been under the Shang; a few chariots on each side for the officers, with peasant infantry to back them up; it was rare for a battle to last longer than a day. As time went on, however, the sizes of the armies increased to several thousand per battle, swords and crossbows were invented, and cavalry replaced chariots when the northern states learned from the Xiongnu how to ride horses.

The new armies needed a different kind of management, and one of the first to realize this was Sun Tzu (also spelled Sun Wu or Sun Zi), author of The Art of War, the oldest existing military manual. All we know for sure about Sun Tzu is that he was born in the state of Qi during the Eastern Zhou dynasty. Sima Qian, a famous Chinese historian that we'll be hearing from in the next chapter, tells us that Sun Tzu was not a soldier by trade, but a farmer and self-taught philosopher; his knowledge about military matters came from his grandfather, a general who had some rare military books. Keep in mind that before the invention of printing, all books had to be copied by hand, so they were always uncommon, expensive, and treated like treasures. Sima Qian goes on to tell us that Sun Tzu lived in the late sixth century B.C., while more recent historians have argued that the tactics described in his manual are compatible with Daoism (see below) and what we know about China after the Spring & Autumn Era, so a later date for the book is more likely. Still others have questioned whether Sun Tzu existed at all; they suggest that a different person wrote each of the book's thirteen chapters. The book became popular in the West after Jean Joseph Marie Amiot, a Jesuit missionary, translated it into French in 1782. Leaders since then who have claimed inspiration from Sun Tzu's work include Napoleon Bonaparte, Admiral Togo Heihachiro, Mao Zedong, and General Norman Schwartzkopf.

One interesting story about Sun Tzu has come down to us. According to Sima Qian, when Sun Tzu was a teenager, his father, a warrior for the state of Qi, rebelled against his duke, and Sun Tzu fled south to Wu, the state at the mouth of the Yangtze River. There as a young man, he wrote The Art of War, in the hope that the king of Wu would see it and make the author his military commander. Twenty years later, He Lu, the king of Wu, read the book and was excited about its potential, so he put it to the test by asking Sun Tzu if the ideas in the book could be used to train an army of women. Sun Tzu replied yes, and the king agreed to let Sun Tzu prove it, by turning the king's harem of 180 concubines into soldiers. First Sun Tzu divided the concubines into two units, and appointed one of the king's favorites as commander of each; then he made sure they understood all his marching orders, before issuing polearms and battleaxes to them. But when he gave them the first order, the girls just started giggling and laughing. In response, Sun Tzu told the king that when the soldiers do not understand an order, it is the general's fault. Then he carefully told the girls how to do the maneuver he had in mind for them, but when he gave the orders, they just giggled again. This time Sun Tzu said that if the soldiers understand an order and do not obey it, the general is not at fault, but the officers under him are; then he ordered the beheading of the two concubines leading the units. The king protested, of course, but he had no answer to Sun Tzu's argument that when a general receives his orders, it is his duty to carry them out perfectly. After the execution Sun Tzu put new "officers" in charge of the units, and as you might expect, he had no trouble getting the concubines to complete the rest of the "drill." Since he had made his point, the king hired him for the job he wanted.

As conflicts heated up and the stakes grew higher, the customs established in the past began to decay. Treachery replaced courtesy, and large states began to swallow up smaller ones. A warning of what was next came from Jin, the state whose duke we already noted did not keep his promises. In 655 B.C. the duke of Jin asked the duke of Yu for permission to pass through his territory so he could attack the state of Guo. The rulers of all three states were descended from the royal house of Zhou, and were thus related. For that reason, an advisor to the duke of Yu urged his master not to allow the Jin army to pass through, arguing that anyone willing to attack a kinsman in Guo would see nothing wrong with attacking Yu as well. The Yu ruler decided instead to let the duke of Jin pass, and paid the consequences. The Jin army went through Guo unopposed, conquered Guo easily, and sacked Yu on the way back, taking its hapless ruler prisoner.

Again, because of their willingness to try new things, the states farthest from the Zhou royal domain were the first to break tradition, and were regarded as uncouth for this. One such example was a famous ambush in Henan province, now called the battle of Maling (342 B.C.). The two opponents here were Sun Bin, general for the state of Qi, and his archenemy, Pang Juan, general for the state of Wei. When their armies met, Sun Bin saw that his force was smaller, and immediately ordered a retreat. As they headed toward Qi, Sun Bin had the troops leave behind first stoves, then siege equipment, fooling the pursuers into thinking that organization had broken down, and the army was coming apart; this trick came to be known as the "Tactic of the Missing Stoves." When they got to a wooded ravine, Sun Bin hid ten thousand archers on both sides, and on a tree in the middle of the ravine, they scraped off the bark and carved the words "Pang Juan dies under this tree." The enemy soldiers arrived at night, and when Pang Juan noticed writing on the tree, he called for a light. The lighting of a torch under the tree was the signal for the archers to release their arrows!

Incidentally, Chinese historians claim that Sun Bin was a descendant of the great Sun Tzu, and that he wrote another military manual, also called The Art of War. Originally it had eighty-nine chapters and four volumes of illustrations, but these were lost around the end of the Han dynasty (see Chapter 3). Then in 1972 A.D., archaeologists opened a Han dynasty tomb in Shandong province that contained a bamboo copy of Sun Tzu's manual, and sixteen chapters of Sun Bin's work, so both versions of The Art of War are now available.

A really bizarre tactic came from Yue, a state in modern Anhui and Zhejiang with an ethnic Vietnamese population; in a 496 B.C. battle their army was led by three ranks of desperadoes who frightened the enemy by beheading themselves!(13) In 473 B.C. Yue went on to conquer another non-Chinese state, Wu; Wu was the first major state destroyed in this conflict.

However, it was Chu, and not Yue, that acquired a reputation for ruthlessness, by confiscating the lands of the states they conquered and exterminating their ruling families.(14) In fact, Chu conquered Yue in 334 B.C., giving it control of all Chinese lands south of the Yangtze. Soon the other states followed suit. By the end of the Spring & Autumn Era the number of Chinese states had been reduced to twelve. Legitimacy no longer commanded the respect that had formerly protected the weaker lords, and the code of chivalry broke down completely. For that reason we call the period between 481 and 221 B.C. the "Age of Warring States."

The Hundred Schools of Thought

While this was a time of chaos, it was not bad in every way. Because the average peasant family was no longer self-sufficient in everything, merchants appeared as the first middle-class profession, taking trade goods from one city to another on the new roads that had been built for the armies. The peasant could also improve his lot somewhat by moving to a city and working in one of the shops that produced various tools and weapons.

Another profession of great importance that arose during this time was the shi, or bureaucrat. Because he was not outwardly ambitious, the bureaucrat was more trustworthy than the noble, and his skills were useful enough to guarantee better treatment than that of his superiors if the state he worked for was conquered. Because of this, and all the turmoil of those days, the Eastern Zhou period was the most intellectually active time in Chinese history. We already saw one outstanding thinker, the military strategist Sun Tzu. Today's Chinese will call the activity of this time the "Contention of a Hundred Schools of Thought," because of the new philosphies and ideologies that sprang up and competed with one another. Two philosophies that sprang up, Confucianism and Daoism, were so different from one another that they have dominated Chinese thought ever since. Another one, Legalism, became the ideology of those who put China back together again, though it proved to be a poor ideology for maintaining control, after the restoration was complete.

Confucius

The large number of governments meant that there was a steady demand to recruit and educate more bureaucrats, regardless of their social class. One of the teachers who did this was Kongfuzi, better known to us by his Latin name, Confucius. If all he did was teach administrative skills, he would have been forgotten by history, but he did more than that; he also taught the formula for a stable political system and an orderly way of life.

Confucius (551?-478 B.C.) was born in Lu, a small state in western Shandong that had been able to hold its own in the wars between the states by staying neutral most of the time. His father, a minor aristocrat & military officer, died when he was four. Though this left his family in poverty, he had such a good education that at the age of twenty-two he began to teach. While giving instruction to the pupils who came to him in increasing numbers, he continued his own study of history, literature, music and ancient customs (especially ritual, in which he early acquired the reputation of an expert), and at thirty, he tells us, he "stood firm," that is, had formed the opinions that did not change for the rest of his life.

An incident of considerable importance in his life was a visit, in 517 B.C., to Luoyang, the royal capital, where he had a long-desired opportunity to see the places where the great sacrifices to Heaven and Earth were offered, to inspect all the arrangements of the ancestral temple of the reigning dynasty of Zhou and its court, and perhaps to pursue researches in the archives. The following years were a period of great disorder in the state of Lu. At first Confucius followed his exiled sovereign to the neighboring state of Qi, but, finding the duke of Qi little disposed to profit by his counsels, soon returned to his native country, where he kept steadfastly aloof from the strife of factions, declining public employment. This was probably the period when he collected and edited the ancient literature with which his name is now connected. In the year 501, however, he was appointed chief magistrate of a city named Zhongdu, and put his theories of administration into practice with such effect, we are told, that in twelve months Zhongdu was a model town. This transformation was noted with surprise by the duke, who asked Confucius whether the same principles could be applied to the government of a state, and being assured that they could, he made Confucius assistant superintendent of public works, and shortly after minister of justice; whereupon, according to his biographers, laws against crime fell into disuse, because there were no more criminals. He strengthened the ducal house and weakened the private families. He exalted the sovereign and depressed the ministers; dishonesty and dissoluteness were ashamed, and hid their heads. Loyalty and good faith became the characteristics of the men, and chastity and docility of the women. Strangers came in crowds from other states. Confucius became the idol of the people, and they made up songs that praised him.

This utopian Lu got the attention of its stronger neighbors, particularly Qi. When the duke of Qi invited the duke of Lu to a peace conference, Confucius warned of possible treachery and persuaded his lord to bring armed guards. Despite this, the meeting proceeded nicely until the duke of Qi provided some musical entertainment. At this point Confucius leaped to his feet and furiously (but politely) told the two lords that this was music fit only to be heard in a palace, and any musician who would play this in an outdoor setting was a barbarian who deserved to die. The duke of Qi was so embarrassed by this musical gaffe that he carried out the suggested punishment, and later gave back to Lu three cities that had been captured in a previous war; the grateful duke of Lu promoted Confucius to prime minister.

Unfortunately he was too thin-skinned to keep the job. One day Qi sent a present of 80 horses and 120 dancing-girls. The duke found this more interesting than the counsel of the sage and declared a three-day holiday for the government. In response Confucius quit his job, and sadly--but slowly, hoping that the duke might repent--shook the dust of the ungrateful state from his feet. Thus ended Confucius' one brief experience as a practical statesman. For thirteen years, accompanied by a band of disciples, he wandered from court to court, offering his counsel and exhortations to princes and ministers; sometimes consulted by them, but not establishing any permanent influence; yet never losing confidence that if one of them would but employ him, "I would effect something considerable in the course of twelve months, and in three years the government would be perfected."

At one point he seemed to have a solid job offer from the king of Chu, but before he could claim it, the enemies of Chu sent troops to surround the Master and his followers, nearly starving them to death in the process. After a few more narrow escapes Confucius returned to Lu (483 B.C.), where he spent his last years writing down what he learned from his studies of the ancient literature, and thinking that his life had been a failure. Recognition would come in full for Confucius, but not in his lifetime. Confucius was a man both behind and ahead of his time; he glorified the virtues of China's past when the kings had actual authority, and it would be more than 250 years after his death before a united China tried what he taught.

Confucius had a basically conservative outlook; he felt that the cause of China's problems was that the rulers and the people had forgotten to keep the rituals of previous eras, and that they were neglecting their duties in other matters as a result. He taught that everything has its place in the universe, and that the way to achieve harmony is to observe the responsibilities of one's station in life. Confucius observed five basic relationships between people: friend & friend, husband & wife, parent & child, elder brother & younger brother, ruler & subject. Only the first of these relationships was on an equal basis; in the other four the person in the inferior position was required to submit to his superior, while the superior was required to use wisdom and look after the welfare of those under him. It was he who first wrote down what is now called the Golden Rule: "What you do not want done to yourself do not do to others." Finally, he had a lot to say about the behavior of those in authority; they should be educated in virtue and classical literature so that they will be inclined to act with justice in every way and not seek vengeance.

In religious matters Confucius was a perfectionist. As a child, we are told, his favorite play was arranging sacrificial vessels and practicing postures of ceremony; as a man he showed the same predilections by antiquarian researches into the ritual of former dynasties. The apparatus of worship at Luoyang drew from him the exclamation, "Now I know the wisdom of the Duke of Zhou, and how the house of Zhou attained to the imperial sway." The ancient music of Shun, the tradition of which was preserved in Qi, so ravished him that for the three months he did not know the taste of flesh: "I did not know," he said, "that music could be made so excellent as this." He believed that the virtue of the people and the welfare of the state depended upon the reverent observance of the sacrifices to the gods and the spirits of the ancestors. He himself "sacrificed to the dead as if they were present; he sacrificed to the spirits as if the spirits were present"; and the crowning proof to him that the Duke of Lu could not be reformed was the haste with which he despatched the solemn sacrifice to Heaven before he hurried back to his pleasures.

Though he never got tired of discussing the minutest points of ritual, Confucius had very little to say about gods or the afterlife; when one student asked about that, Confucius replied, "You do not understand even life. How can you understand death?" Today he is usually classified as a philosopher, but Confucius was not a speculative thinker; the problems of the origin of the universe, the nature of being, the one and the many, which exercised the philosophers of Greece and India, lay beyond the horizon of his mind. His commonsense philosophy dealt exclusively with the practical questions of ethics and politics. To him, as to other thinkers of this type, God was essentially the moral order of the world, a set of rules enforced in the phenomena of nature as well as in the course of history and the destiny of individual lives. The more uniform, that is, the more unvaryingly moral, this order is, in the interest of ethics, conceived to be, the more impersonal the conception becomes, and it is the following of this moral code that makes for righteousness. According to this point of view, if the destiny of men is determined by nothing but their conduct, it is obviously futile to make Heaven change it: "He who offends against Heaven has none to whom he can pray." Once when Confucius was ill his disciple, Zelu, asked leave to pray for him. He said, "Is that proper?" Zelu replied: "Yes. In the Prayers it is said, 'Prayers has been made to the spirits of the upper and lower worlds.'" The Master said, "It must be a long time since I prayed." Nevertheless, years later his teaching would be made into the state religion, and Confucius himself would be deified.

Daoism

Though arguably the most important figure in Chinese history, Confucius was not the only important teacher in this age. A generation earlier there lived a sage named Laozi ("Old Master," 604?-531? B.C.). Laozi took a completely different look on the world; instead of achieving order by following civic obligations, Laozi called for a complete escape from the chaos and injustice of his society; his solution was to return to nature and create a primitive utopian community, where there would be no place for envy or exploitation. The fact that this state existed only in the imagination of Laozi and his followers did not deter them, for they always considered permanent ideals to be more important than shifting realities.

Lao-tzu pointed out that in nature all things work silently; they fulfill their function and, after they reach their bloom, they return to their origins. Unlike Confucius' ideal gentleman, who is constantly involved in society in order to better it, Lao-tzu's sage is a private person, an egocentric individualist. Instead of focusing on relationships, Laozi taught that everything in the universe is made up of a mixture of two kinds of energy: a positive, warm, dry, male force called Yang, and a negative, cool, wet, female force named Yin. To Laozi the way to find harmony was to understand the nature of Yin & Yang, and achieve a perfect balance between them in both body and mind. He called this philosophy, based on non-interference and cooperation with nature, Dao, meaning "the way"; for this reason the religion he started is now called Daoism.(15)

Daoism is a revolt not only against society but also against the intellect's limitations. Intuition, not reason, is the source of true knowledge. Books, Daoists said, are "the dregs and refuse of the ancients." Consequently Daoist teaching is difficult to put into words; they put it this way, "The one who knows does not speak, and the one who speaks does not know." But Daoist mysticism is more philosophical than religious. Unlike Hinduism, it does not aim to extinguish the personality through the union with the Absolute or God. Rather, its aim is to teach how one can obtain happiness in this world by living a simple life in harmony with nature.

Confucianism and Daoism became the two major molds that shaped Chinese thought and civilization. Although these rival schools frequently sniped at one another, they never became mutually exclusive outlooks on life. Daoist intuition complemented Confucian rationalism; during the centuries to come, Chinese were often Confucianists in their social relations and Taoists in their private life. For example, Daoism gave solace to those who were suffering, while Confucianism did not. Daoism also would in time have a deep impact on Chinese poetry and art. Ironically, by making a life of contemplation acceptable to the Chinese, the Daoists made it possible for a foreign religion, namely Buddhism, to come into China and gain widespread acceptance.

Mozi

Between 500 and 200 B.C., a number of other thinkers came along and elaborated on what Confucius and Laozi had to say. One of the earliest whose teachings have come down to us is Mozi (479-381 B.C.). Mozi started out with a Confucian-style education, but his message diverted so much from that of Master Kong that it can be called a Confucian heresy. He attacked the coldness and formalism of traditional Confucianism, and offered in its place a doctrine of universal love that sounded much like Christianity. For him there was only one cause for all of society's ills: men of every class and condition love themselves and do not love their fellows; hence they wrong others for their own advantage. There is therefore one simple remedy--mutual love. Rather than grade love according to the relationship of the people involved, as Confucius did, Mozi argued that all men should love each other equally, since Heaven does not play favorites with mankind. For if men loved one another as every man loves himself, there would be no more crime. If each regarded his neighbor's house as his own, who would then steal? If each regarded his neighbor's person as his own, who would rob? If princes regarded foreign states as their own, would there be any reason for wars? All the misery in the world--the overpowering of the weak by the strong, the oppression of the minority by the majority, the defrauding of the simple by the shrewd, the haughtiness of the eminent toward the insignificant--is due to the making of distinctions between men, whereas universal love embraces them all, without making such differences. Warfare is never justified except to defend oneself from aggression, and that will no longer be needed when the idea of loving one's neighbor is universally accepted. When asked how this millennium is to be brought about, Mozi answered, with characteristic Chinese faith in the influence of the ruler, that if princes would only show that they delighted in the love of all for all, the people infallibly would cultivate it. His most famous saying raised eyebrows: "A man of Chu is my brother." By this time non-Chu Chinese wondered if the Chu were really human; sometimes they called them "apes wearing hats."

Although Mozi looked to the legendary past to demonstrate the results of virtuous conduct, the way Confucius had done, his philosophy also had a more practical aspect. He denounced all activities that did not improve the lives of the common people, like militarism, luxury, and expensive rituals. All resources should be devoted toward providing the three basic needs of food, clothing, and shelter, and all waste should be eliminated. He especially denounced the waste of money used to stage expensive funerals, and the waste in productivity caused by the traditional three-year mourning period following the death of one's parents, both of which were prescribed by Confucius. Because these teachings had a wide appeal, particularly to the poor, Mozi gained a large following quickly, but he always had trouble getting official backing (the dukes and kings loved his message on love but couldn't run their states on it).

Yang Zhu

At the opposite extreme from the radical altruism of Mozi was Yang Zhu, a pessimist who lived about the middle of the fourth century. To him life is short and full of trouble; death is the end of all. The only profit in this evil world is to enjoy the pleasures of sense while we can, without sacrificing a hair to the interests of mankind or the welfare of the state, and regardless of the praise or blame of men. None is more famous than Shun, Yu and Confucius. Those heroes of virtue never had a day's enjoyment in their lives. Though their fame endures for ten thousand generations, what is that to them? The dead know nothing of the praises bestowed upon them; they are no better than a stock or a lump of clay. None is more infamous than Jie Gui and Di Xin; yet those tyrants in their lifetime enjoyed to the full riches, power, and honor, and what do they care now for the curses of posterity? The ancients knew this, and followed their natural inclinations; they did not make a virtue of denying themselves the pleasures that came in their way, nor let themselves be urged by ambition for fame to put constraint on their natures.

Mencius

The most important of the Confucians was Mencius (the Western name for Mengzi, 372-289 B.C.). Unlike Confucius, who always looked for a powerful position which would allow him to put his theories into action, Mencius seems to have been happy as a wandering teacher, traveling around with a crowd of students, visiting palaces, and criticizing his hosts (so much easier when you're not job-hunting). His works, consisting largely of discussions, surpass the Confucian Analects in logic and in orderly presentation. He employed dialogue with much skill to refute an opponent or to show the superiority of his own proposition, in a dialectic fashion which at times reminds us of Socrates.

Though Mencius also looked to the past for solutions to the problems of the present, the increasing political strife of the time meant that he was much more concerned with present-day society than his predecessors had been. Steering for the middle ground, he attacked the teachings of both Yang Zhu and Mozi. The attitude of the former--"every man for himself"--is anarchism; the altruism of the latter--"love all men equally"--is unfilial: both strike at the roots of human society. And Daoism was equally bad; to Mencius the extreme individualism of the Daoists was nothing but a form of selfishness. He would have agreed with a later Confucian writer who summed up in one sentence the teaching of a famous Daoist: "He would not pluck so much as a hair out of his head for the benefit of his fellows." If these false doctrines should prevail, they would reduce men to the state of the beasts, who acknowledge neither king nor father; benevolence and righteousness would cease, and men would devour one another. If this is to be averted, they must be stopped, and the sound principles of Confucius reaffirmed.

Mencius called for the bringing back of an ancient land management program known as the well field system. According to this system, which may never have functioned exactly as described here, 150 acres of farmland were divided into nine equal portions. Eight families each had a plot which they farmed for their own needs, and together they worked the ninth plot to produce the government's revenue. As far as Mencius was concerned, the state exists for the people, and its stability depends on the welfare of the people. The government must preserve peace abroad and order at home; it must not burden the people with forced labor on public works by which they are withdrawn from their fields, nor harass them with a complicated system of taxes and imposts; it must instruct, encourage, and, if necessary, assist the tillers of the soil, for on agriculture the prosperity of all depends. To reduce the people to starvation by misgovernment or neglect is sheer murder.

"If the people have not a certain livelihood, they will not have a fixed heart. And if they have not a fixed heart, there is nothing which they will not do in the way of self-abandonment, of moral deflection, of depravity, and of wild license. When they thus have been involved in crime, to follow them up and punish them - this is to entrap the people. Therefore an intelligent ruler will regulate the livelihood of the people, so as to make sure that, above, they have sufficient wherewith to serve their parents, and, below, sufficient wherewith to support their wives and children; that in good years they shall always be abundantly satisfied, and that in bad years they shall escape the danger of perishing. After this he may urge them, and they will proceed to what is good, for in this case the people will follow after that with ease."

Mencius is also credited with establishing the doctrine of the Mandate of Heaven in the form we are familiar with (see Chapter 1). He summed this up with the quotation, "Heaven sees as the people sees; Heaven hears as the people hears." Thus he gave justification to revolution: "If a prince have grave faults," he once told a king to his face, "the nobles and ministers who are of his blood ought to remonstrate with him, and if he do not listen to them after they have done so again and again, they ought to dethrone him." The murder of a tyrant like Di Xin was more like the removal of a common criminal than the putting to death of a sovereign; by his crimes he had forfeited all right to a better name than ruffian and robber or to different treatment. Where Confucius had upheld the hereditary right of rulers, Mencius had turned them into replaceable servants of the people who had a right to stay only so long as they ran a just and efficient administration.

Xunzi

By the end of Mencius' career the old order had decayed to the point that many no longer had any hope in restoring it. The foremost sage of the early third century, Xunzi (298-238 B.C.), felt it was time to take a more realistic look at both society and Confucianism. Unlike Confucius and Mencius, he was a career politician who held high offices in Qi and Chu, and therefore could not ignore the reality of his day in favor of some impractical utopia. To start with, he attacked the fortunetellers that heads of state went to for guidance on Heaven's will and what the future might bring. To Xunzi these diviners were charlatans who claimed control over forces no man could take charge of, and that while Heaven may exist (and he questioned whether it did), no mortal can understand or manipulate it. Instead, he saw the true sage as a political activist who improves humanity through positive, rational efforts.

Xunzi also broke with his predecessors by declaring that mankind left to his own devices is fundamentally evil; he must learn to control selfishness, greed, envy and hatred, and that is done through the laws of the state and the discipline of education. This concept, more than any other, led to his denunciation as a heretic by later Confucians, who see mankind as basically good and relationships as more important than laws. They also noted that two of Xunzi's students later founded Legalism.

Zhuangzi

Among the Daoists the important thinker after Laozi was Zhuangzi (389-286 B.C.). Unlike most of the sages, Zhuangzi had a sense of humor and a laid-back personality. He expressed his points by telling fables, often collected from his own experiences. He also would not pass up an opportunity to make fun of the Confucians, whom he saw as tiresome busybodies. For instance, one story tells of Zhuangzi going to Lu, the home state of Confucius. The duke of Lu tried to brush him off by saying this was a Confucian state, with very few followers of Daoism. Zhuangzi replied by noting that he saw plenty of people in the duke's court dressed like Confucians, but how many of them were really Confucians? He then suggested that the duke pass a decree ordering that anyone who wears Confucian clothes without practicing Confucian doctrine be put to death. The duke agreed and the courtiers ditched their clothes as soon as they heard the news. Five days later the only person found in the state wearing Confucian clothes was an old man, who was a champion at quoting what the Master taught. Zhuangzi had proved his point; there was only one Confucian in Lu!

Zhuangzi saw the world differently from most people, and even questioned the reality of the world of the senses. He said that he once dreamed that he was a butterfly, "flying about enjoying itself." When he awakened he was confused: "I do not know whether I was Zhuangzi dreaming that I was a butterfly, or whether now I am a butterfly dreaming that I am Zhuangzi."

Zhuangzi also saw uselessness as a virtue, and frequently said, "No one seems to know how useful it is to be useless." He argued that just as a useless tree is not cut down for wood, and a useless animal is not butchered for food or put to work, so a useless man will not be exploited by other men. Another one of his stories emphasized that point. One day Zhuangzi was fishing when two courtiers approached him with an official document from the prince of Chu and said, "We hereby appoint you Prime Minister." In response, Zhuangzi told a story: "I am told there is a sacred tortoise, offered and canonized, three thousand years ago, venerated by the prince, wrapped in silk, in a precious shrine on an altar in the temple. What do you think: Is it better to give up one's life and leave a sacred shell as a cult object, surrounded in a cloud of incense for three thousand years, or better to live, as a plain turtle, dragging its tail in the mud?" One of the courtiers answered, "For the turtle, better to live and drag its tail in the mud!" Whereupon Zhuangzi said, "Go home! Leave me here to drag my tail in the mud!" Ideas like this, when combined with Buddhism a thousand years later, eventually gave rise to the doctrine we call Zen Buddhism.(16)

Legalism

In the state of Qin, a very different philosophy arose to become the official ideology: Legalism. The two most important Legalist philosophers, as noted above, were students of Xunzi: Han Feizi (280?-233 B.C.) and Li Si (?-208 B.C.).

Han Feizi thought the Confucians were fools for believing that restoring the rituals of the past would fix the problems of the present.(17) The problem with Confucianism, he said, is that people will always be more loyal to their families than to their king. Therefore, a king is wasting his time when he tries to make people like him. Furthermore, the government wastes its revenue by supporting men of learning like the Confucians, who not only cannot solve current problems but are more interested in the welfare of the people than in helping their patron.

Han Feizi argued that human nature cannot control itself without laws; the common people will object to activities that benefit them in the long run. Regardless of what the people say, it is best for everybody when the ruler conscripts labor to farm more land, and fills the granaries and treasury by taxation, so that the state will always be prepared for famine or war. The ruler should also remove troublemakers by any means possible to keep the peace, and require universal military training and service. As for the people, they must be regulated by a system of strict laws, rewards and punishments. Once all this is set up properly, the machinery of government will function so efficiently that the ruler will no longer have to do anything at all. In short, what the ruler wants is right, and what the ruler doesn't want is wrong. This kind of state, in which well-cared for, but ignorant subjects blindly obeyed the dictates of an absolute ruler, has much in common with the government of present-day Communist China.

Followers of Legalism could be ruthless toward one another. One day the ruler of Han sent Han Feizi to negotiate with the western state of Qin. There he was politely received by its king, the future first emperor Shihuangdi, who had read his book on ethics. However, Qin's chief minister Li Si, an occasional pupil of Han Feizi, didn't trust him, and persuaded Shihuangdi to throw him in jail on a charge of espionage. Then Li Si ordered Han Feizi to commit suicide by drinking poison; shortly after that Shihuangdi decided that the accusation of spying was false, but by then it was too late.

Despite their falling out, Li Si agreed with Han Feizi's views. He saw little to gain from studying ancient classics, and felt that universal military service and conscript labor was acceptable because the needs of the state outweighed the needs of the individual. He also called for harsh punishments, even for petty crimes: "Only an intelligent ruler is capable of applying heavy punishments for light offenses. If light offenses carry heavy punishments, one can imagine what will be done against a serious offense. Thus the people will not dare to break the laws." It was the followers of Legalism who restored order in the late third century B.C., and it is also no coincidence that Li Si went on to become the first prime minister of reunited China.

This is the End of Chapter 2.

FOOTNOTES

1. There are also some unusual legends concerning the accomplishments of Yu before he accepted the crown. According to one, when Yao was king there occurred a flood of the Yellow river that devastated the whole country. Yao first appointed a man named Kuan to control the river and repair the damage to the fields and villages, but Kuan was incompetent, so when Kuan's son Yu grew up the assignment was passed on to him. The task was so enormous that it took Yu nine years to finish it, and the grateful Chinese said, "We should all have been fishes, if it had not been for Yu." Whether this was really the worst flood in Chinese history or a vague recollection of Noah's flood is one of the questions whose answer has been lost over time.

In the reign of Shun, Yu was sent to explore/survey the world, for the purpose of seeing how much of the world's geography had been changed as a result of the flood. Henriette Mertz, in her book Gods From the Far East, looked at some of the travel logs that supposedly come from Yu's expeditions, and found that the described landmarks do not match places in China, but they do match places in western North America. This implies that the Chinese discovered America 3,700 years before Columbus! I discussed this theory more in Chapter 1 of my North American history.

2. Unlike the Middle East, China went directly from stone age to bronze age technology, without a copper tool-using period in-between. This is often seen as evidence that China learned metallurgy from somebody else. For a long time Middle Eastern traders were considered the most likely agents, but the discovery of 5,000+ year-old bronze vessels and jewelry in Thailand now suggests a Southeast Asian origin.

3. Not knowing what caused eclipses, the ancients were terribly upset by them. Astronomers were also responsible for keeping the calendar accurate, so the king probably thought that they had let the calendar slip if they did such a slipshod job on eclipses.

4. According to Chinese records, the seat of the Shang court was moved no less than six times, and Anyang was the youngest, serving as the capital from the fourteenth century B.C. until the dynasty's overthrow. Two older capitals besides Anyang have been excavated so far, and they show a continuous development going back before 1500 B.C., meaning that Chinese civilization could not have been suddenly introduced from the West, as many Western historians have fondly believed. Why the Shang court moved so often is not known; perhaps they were looking for a site that was safe from the northern barbarians, who had already become China's archenemy.

5. We see the sudden introduction of horse-drawn chariots in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and India at roughly the same time, the mid-second millennium B.C. Because of this some scholars think the Shang were not full-blooded Chinese, but descendants of the same people who invaded with the chariots originally.

6. Longshan sites also produced oracle bones, but there was no writing on them, indicating that writing was not in use at that time. Legends claim that before the invention of writing they kept track of things by tying knots in strings, like the quipus of ancient Peru.

7. Very few Shang tombs have been found intact, in part because more than three thousand years have passed since the burials. The best preserved grave found so far is that of the aforementioned Fu Hao, discovered outside of Anyang in 1976 A.D.

A very interesting collection of smashed bronze statues, one of them nine feet high, turned up in 1986 at Sanxingdui, in western Sichuan province. Those who made the statues were not Shang Chinese--we know that much. It seems that the statues were used as a merciful alternative to the human sacrifices of the Shang; when the gods called for sacrifices, the residents of Sanxingdui destroyed statues of people, instead of the real thing. It is now believed that Sanxingdui was the state of Shu, which is first mentioned in Chinese records at the end of the Shang dynasty.

In 2001 a bulldozer dug up a collection of gold and jade objects at Chengdu, the capital of modern Sichuan. Since then more gold, jade, bronze and stone artifacts, pots and elephant tusks have been discovered. The producers of these rich treasures lived around 1000 B.C., and are called the Jinsha culture (Jinsha is another name for the upper Yangtze River). This may have been the culture of Ba, a loosely organized kingdom reported in eastern Sichuan during the Zhou dynasty.

8. Politics makes people behave in strange ways. After Wu Wang took charge, China's non-Chinese neighbors expressed their wishes for a happier, more peaceful era by sending him gifts (tribute). From a tribe named Lu came some intelligent dogs who "knew their master's mind." The king was thrilled, but the chief minister said he should give the dogs away! The reason was pure xenophobia: "Never let a barbarian know he has something you want. Value nothing that comes from far away!" Thus the traditional Chinese avoidance of foreign things became official policy, and has been for most of the time since.

9. Strange as it may sound, the Chinese were unfamiliar with rice until they settled hot, wet lands where it could be grown. This is definitely not the type of climate found on the cold north China plain; a line drawn from the Qinling mts. in Shaanxi to the Huai river in Jiangsu marks the northern limit of the rice-growing zone.

10. Other Chinese regarded the Chu as uncultured hillbillies; the name Chu in fact means "forest." The leaders of the other states had too much respect for the Zhou dynasty to call themselves kings until after the Spring & Autumn Era had ended.

11. After 500 B.C., Qi lost its leading role. This probably happened because by this time it had conquered the last barbarians on its borders, in eastern Shandong, and now could only increase its territory at the expense of other Chinese states. The nearest non-Chinese tribes now lived in Manchuria, and the responsibility of subduing them went to a state named Yan, in Hebei province.

12. The opposite of chivalry is guerrilla warfare. Mao Zedong once said, "I am not the duke of Song."

13. Though it worked, this tactic was not often used for obvious reasons.

14. Two lords defeated by Chu expected the worst and brought coffins with them when they came to surrender. They were spared, but others were not so lucky.

15. Daoism is spelled Taoism in older books, and there Laozi's name appears as Lao-Tzu.

16. The original name for Zen Buddhism was Chan; it became known as Zen after the Japanese learned it from China.

17. For Confucians preoccupied with tradition, Han Feizi told this story: "There was a farmer of Song who tilled the land, and in his field was a stump. One day a rabbit, racing across the field, bumped into the stump, broke its neck, and died. Thereupon the farmer laid aside his plow and took up watch beside the stump, hoping that he would get another rabbit in the same way. But he got no more rabbits, and instead became the laughing stock of Song. Those who think they can take the ways of the ancient kings and use them to govern the people of today [e.g., the Confucians] all belong in the category of stump-watchers!"

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A Concise History of China

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|