| The Xenophile Historian |

A History of Africa

Chapter 2: VALLEY OF THE PHARAOHS, PART IV

Egypt before 664 B.C.

This chapter is divided into two parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| The Gift of the Nile | |

| Most Ancient Egypt | |

| The Archaic or Protodynastic Era | |

| The Pyramid Age | |

| Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt | |

| Egyptian Mathematics and Science | |

| Ancient Nubia | |

| The End of the Old Kingdom |

Part II

| The First Intermediate Period | |

| The Middle Kingdom | |

| The Second Intermediate Period | |

| The Rise of the New Kingdom |

Part III

| Thutmose the Trendsetter | |

| The First Feminist | |

| Imperial Egypt | |

| The Amarna Revolution |

Part IV

| The Ramessid Age Begins | |

| Ramses the Great | |

| The Latter Ramessids | |

| The Third Intermediate Period | |

| Go to Page Navigator |

The Ramessid Age Begins

Ramses I was apparently an old man when he got the crown, for he only ruled for sixteen months, just long enough to get the XIX dynasty started. He also abandoned Thebes, choosing Avaris, the former Hyksos base in the eastern Nile delta, as his capital. Henceforth, this city would be called Pi-Ramesse, the Biblical Raamses. We now believe that Ramses came from a Lower (northern) Egyptian family, so this was probably his hometown, but it also showed another break with the pharaohs of the previous dynasty; Ramses and his successors would be more concerned with what was happening north and east of Egypt, than they would be about religious affairs in Thebes. Finally, Ramses was buried in the Valley of the Kings like his predecessors, but because his reign was so short, only a small tomb was built for him: it had one corridor, one stairway, and one chamber (And see Footnote #38 for the journeys Ramses went on after his death.).

Ramses' son, Seti I, was the most vigorous military commander since the Thutmoses. He led four campaigns into Israel and Syria, though the Hittites frustrated his efforts to conquer the latter. At home, Seti was an ambitious builder, starting the great Hypostyle Hall at the temple of Karnak, building a vast new temple complex to Osiris at Abydos, and constructing for himself the best decorated tomb in the Valley of the Kings.(35) These accomplishments mark Seti as a great pharaoh, but nowadays he is overshadowed by his son Ramses II, ancient Egypt's greatest builder of all.

Seti remembered how his father got to be pharaoh, and did what he could to make sure his dynasty would endure. First, he revived the practice of installing a co-regent. Ramses II left a delightful inscription on Seti's temple project at Abydos, where he stated that he had been crowned as a small child, so that Seti could see what the next pharaoh looked like while he was alive. Next, when Seti marched off to fight a defensive action against Libyan tribesmen, who were now trying to move into the Nile valley, he took young Ramses with him. This gave Ramses some military experience that he would put to use later on. Finally, Seti provided Ramses with two wives, Nefertari and Istnofret, and several concubines, and told him to get started producing his own heirs as soon as possible. When he grew up, Ramses showed he had learned his lessons well; at the age of twenty-two, he led a chariot charge that crushed another revolt, this time in Nubia, and brought two sons along, aged five and four, on that campaign. Soon after that, he also launched a successful ambush of the Shardana, some Mediterranean pirates (from Anatolia?) who had infiltrated the Nile Delta. By the time of Seti's death, the two wives of Ramses had given him ten children, four sons and six daughters; he may have had children by the concubines as well.

In 2024, a team of Egyptian archaeologists was excavating a fortress on the western edge of the Nile delta, built in the XIX dynasty to keep the Libyans out. Besides some artifacts identified as personal belongings of the soldiers stationed there, they found a half-meter long sword forged from a single piece of bronze, with the names of Ramses II on the blade. Thus, news stories about the discovery called it "the Sword of Ramses," but it probably didn't belong to him. It is more likely the pharaoh gave the sword as a gift to somebody in the fort, possibly the commanding officer, either as a reward for good service, or to make sure the recipient stayed loyal. Normally an ancient Egyptian sword looked like an oversized sickle, and was called a kopesh, but this shows that Egyptian smiths could also make straight swords.

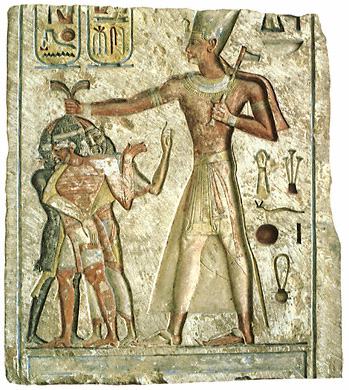

Ramses II ruled a total of 67 years (probably 940-873 B.C.); of all the pharaohs, only Pepi II, back in the Old Kingdom, may have ruled longer. He spent his first few months at Thebes, starting the construction of the buildings that would become important at the end of his reign: his tomb, and his mortuary temple, now called the Ramesseum. Because no one knew how long a king would live, or how much time he would have to work on his funerary monuments, it made sense to get started on them as soon as possible. As it turned out, the long reign of Ramses allowed him to build a tomb and temple for himself that were larger than average. His time in Thebes coincided with the Opet festival, a major holiday where idols of the Egyptian gods were brought out of the temple at Karnak, put on boats, and carried in parades through Thebes. Since the pharaoh was expected to take part in this festival, by talking to the images and offering incense to them, Ramses worked his attendance at the festival into his schedule before moving on. Next, he completed the works that his father Seti had started, at Karnak, Abydos, and finally at Pi-Ramesse (see Footnote #35). At each site, he added relief sculptures that showed himself presenting offerings, either to the gods or to Seti, who now was considered a god, too. The last project put him back in the capital. By now Ramses was into his second year, and he felt he needed to go to Syria and teach the Hittites a lesson.

The campaign Ramses fought against the Hittites is worth recounting in detail, for the main encounter between the two armies, the battle of Kadesh, was preserved for us by both sides, making it the first battle in history for which detailed tactical information is available. Ramses arrived on the scene with the whole Egyptian army, divided into the four brigades of Amen, Ra, Ptah, and Sutekh (Set). As he approached Kadesh from the southwest he could not see that a slightly larger Hittite army was waiting for him, because it was hiding on the other side of the city. He became overconfident when he found some nomads with pro-Hittite sympathies, who told him that the enemy had retreated to the north when they heard the Egyptians were coming. Eager to catch up with them, Ramses took the Brigade of Amen and marched around the city's west wall, leaving the other three brigades several miles behind. Meanwhile the Hittite general, Hattusilis (the younger brother of King Muwatallis), moved his army south along the east wall, keeping the city between himself and the pharaoh.

As Ramses reached the banks of the nearest river, his troops captured two spies in the Egyptian camp, and beat them until they got a confession of what was really happening. Too late, Ramses realized that he had walked into a trap. At that point, 2,500 Hittite heavy chariots ambushed the Brigade of Ra on the south side of the city, cutting one fourth of the Egyptian army to ribbons. The survivors fled north to the Brigade of Amen, and Hattusilis pursued them, cutting off Ramses from his reinforcements and avenue of escape. Trapped with his back to the river, Ramses might have ended his career there, had not Hittite discipline broken down when they saw an opportunity to raid the pharaoh's camp. Ramses saved himself by driving the nearest enemy soldiers into the river; then the Brigade of Ptah arrived just in time, allowing him to get away. He ran back to Egypt, adorned temples with pictures of his most heroic moment, called himself "Ramses the Great, conqueror of the Hittites," and fooled the world into thinking that he had won a glorious victory.

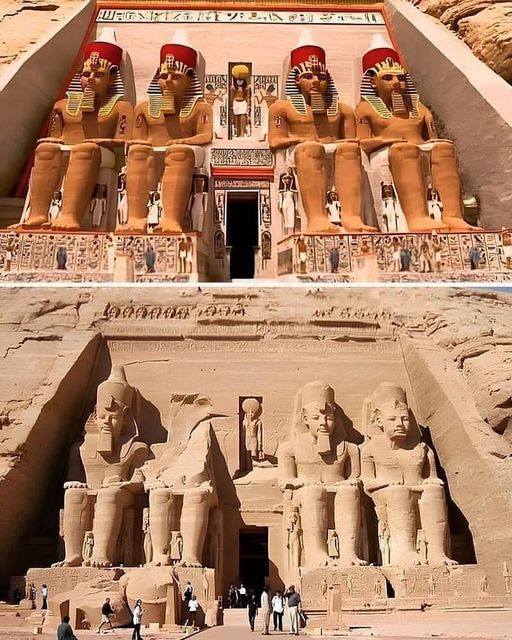

To avoid any more such "victories," he abandoned the whole Levant to his enemy. The Hittites now marched all the way to the border of Egypt itself. Ramses spent the next fifteen years leading more campaigns into Asia, fighting to hold what should have been his in the first place. In the twenty-first year of his reign both sides got tired of it all, and they signed the first peace treaty on record, which gave Syria to the Hittites and a Hittite princess to Ramses. Ramses spent the rest of his career at home, fathering an army of children(36) (we know that he had 92 sons and 106 daughters), and built more monuments than all the other Pharaohs put together, sometimes using stones and statues appropriated from earlier dynasties. In the process he became the standard against which all future Egyptian kings would be measured. Today, whether you visit ancient Memphis or the huge temple at Abu Simbel, there is no place in Egypt where you won't find some statue or inscription of his; it was one of those fallen statues that inspired the nineteenth century poet, Percy Shelley, to write his famous sonnet about "Ozymandias, king of kings." Well, that's show business!

The Latter Ramessids

Ramses was succeeded by his thirteenth son, Merneptah (also spelled Merenptah), because the first twelve sons died before their long-lived father did. Think about that for a moment; very few people have twelve children, let alone outlive twelve sons. When the throne finally passed to Merneptah, he was nearly sixty years old. However, he was up to dealing with a challenge that could have beaten a younger man. In his fifth year a coalition of hostile Libyan tribes invaded Egypt, and they brought with them mercenaries from across the Mediterranean. Seti I and Ramses II had employed such mercenaries previously, so if the Libyans had indeed subverted them, then much, if not all of Lower Egypt, was in danger. Merneptah met them head-on, killed 10,000 in the resulting battle, and commemorated his victory in an inscription now called the "Israel stele," because at the end, where the defeated enemies of Egypt are listed, is the first mention of Israel by name in Egyptian records: "Israel is laid waste, his seed is not."

Victory against the Libyans did not halt a peaceful invasion of immigrants from the west, looking for food, better jobs and homes; we'll hear from them again later. We also know that starting in the seventh year of his reign, Merneptah purged the government; almost all the senior officials under him were replaced. Among them was a brother named Amenmesse, who had served as viceroy of Nubia. This position was not only a powerful one, but a lucrative one as well, since most of Egypt's gold now came from Nubia. Losing this job may have been the trigger that prompted Amenmesse to claim the throne for himself.

With Merneptah's death, the XIX dynasty became unravelled. Ironically, this happened because Ramses II had left so many kids behind. Now the dynasty had too many potential heirs, rather than no heirs, as was the case with the XVIII dynasty. Unfortunately, records are scant for the years between Merneptah and Ramses III, so the events mentioned in this paragraph and the next two are largely guesswork. Merneptah was followed by four short-lived rulers: his son Seti II, Amenmesse, Siptah (Amenmesse's son?), and Twosret (Seti's wife). When the crown passed from Merneptah to Seti, Amemesse acted, declaring himself pharaoh six months later. Starting from his power base in Nubia, Amenmesse advanced northward. Alas, we have no records of military campaigns from Seti's reign; the inscriptions we do have from him are mostly religious texts, plus a few texts that mention mining expeditions in the Sinai peninsula. Therefore we don't know if any battles were fought on the way; if there were battles, we don't know if Seti led the army, or if he sent a general. At Thebes, Seti II had started building new temples, so Amenmesses erased Seti's name from those works, and put his own name there. After that Amenmesse's name turns up in inscriptions as far north as the Faiyum, suggesting that he conquered all of Upper Egypt, while Lower Egypt remained in the hands of Seti. Amenmesse's usurpation was apparently brief, for he disappears from all records and inscriptions, only four years after he launched his campaign. Once again, we don't know what happened. He could have died, he could have been defeated, or the two rivals could have reached a peaceful settlement, in which Amenmesse agreed to step down. Whichever case it was, the lands Amenmesse controlled returned to Seti by default. Seti put his name back on his new temples in Thebes, and resumed their construction.

We know that Seti II got help from two important individuals, because of the rules of Egyptian art. Normally when a pharaoh was portrayed with anyone else, the others were standing/kneeling/prostrating before him, paying homage or presenting offerings. In this case, however, the others are shown standing behind him. This means they were support personnel, taking the spot where the gods were normally shown. One of them was his queen. Twosret; no surprise there. The other was more unusual, a character we call Chancellor Bay. At the beginning of his reign he was a scribe or butler; apparently he was quickly appointed to the job of vizier. Even more remarkable, he was not Egyptian; he was described as a "Syrian," so he came from somewhere in the Levant, meaning he could be an Aramaean, Canaanite, or even possibly an Israelite.

The next pharaoh was Siptah, a short-lived, sicky youngster. He may have checked out when he was only sixteen years old, and his mummy shows both a club foot and evidence of polio. We don't even know if he was the son of Merneptah, Seti II or Amenmesse; some have suggested the latter, because Siptah's name was not included in king lists during the XX dynasty, as if he was not regarded as a legitimate ruler. Afterwards, Tausret took over, becoming one of the few female pharaohs in Egyptian history (remember Merneith, Sobek-Neferu, and Hatshepsut). We think she only lasted for a year, two at the most, but a reign of six years is credited to her, suggesting that the years of Siptah's reign were added to her own. Finally, we don't know how her reign ended, because Egypt was in a state of civil war at this time. As a later inscription put it: "One united with another in order to pillage; gods were treated like men, and offerings were no longer brought to the temples." During this time, the most powerful man in Egypt was not a pharaoh but a treasurer named Chancellor Bay, who had enough influence to build a tomb for himself in the Valley of the Kings. The land was rescued from this sorry state by a man of unknown origins named Setnakht, who like Ramses I, only lasted long enough to start a new dynasty.

The second pharaoh of the XX dynasty, Ramses III, sought to imitate the life and actions of the previous Ramses to the smallest detail; he took all the names of the great pharaoh for himself, and gave his sons the same names and titles that Ramses II gave his sons. Then fate gave him a chance to prove himself on the battlefield the same way his role-model did. The Libyans returned with their allies, Greeks and other folks from Europe which the Egyptians called the "Peoples of the Sea," and a tribe called the Pereset (the Biblical Philistines?). This time it took three battles to defeat them: one on the western frontier, one in Israel, and a naval battle in the Nile Delta.(37) Afterwards he celebrated his victories, the last great display of Egyptian imperial might, in true Ramessid fashion: he built a grand temple shaped like a fortress at Medinet Habu, and enlarged those built by his predecessors, like Karnak.

All the activities of the XIX and XX dynasty pharaohs were, as you might expect, astronomically expensive. Even without the monument-building, there was the task of maintaining the army, which now was made up largely of foreign mercenaries (mercenaries always demand more pay for their services than what the local recruits get). Another drain on the royal treasury was the revived priesthood of Amen-Ra. During the thirty-one-year reign of Ramses III, his scribes reported staggering contributions to support the priests: 169 towns, 113,433 slaves, 493,386 head of cattle, 1,071,780 plots of ground, eighty-eight ships, and lots of gold, silver, and jewels. And every time a new temple was built, it meant there would be less land for the pharaoh to collect taxes from, since the clergy, like today's, were tax-free. As the priestly cults and mercenaries grew richer, everyone else got poorer. At one point Ramses III even ran out of grain to pay the hungry workers on his tomb; they went on strike, but in the end received only half the wages due to them.

Eventually a conspiracy from the harem murdered Ramses III, but the conspirators failed to keep his son, Ramses IV, from taking the throne. Ramses IV prayed to the gods for a lifespan twice as long as that of Ramses II--but he only ruled for six years. The next seven pharaohs after him all bore the name of Ramses (which they saw as a good luck charm), but none of them did anything important. Under them the problems of poverty, increasing power in the hands of the priests, etc., were not solved. Many peasants turned to an age-old solution for their poverty--grave robbing. According to the legal documents of the XX dynasty, grave robbery reached epidemic proportions, and the thieves had the assistance of some priests and guards, who looked the other way in return for a share of the loot.(38)

Nubia revolted during the reign of Ramses XI, the last pharaoh of the dynasty. Panehsy, the viceroy of Nubia, marched on Thebes in Ramses' twelfth year, chased away the high priest of Amen, Amenhotep, and confiscated the temple lands to give to his veteran troops. Then he tried to add Upper Egypt to the area under his authority, but he was an unpopular governor. Seven years later a junior officer named Herihor, who appears to have been Amenhotep's son-in-law, was put in charge of the army that took back Thebes. Herihor's son Piankh chased Panehsy all the way back to Nubia, and Herihor assumed the titles of vizier, viceroy of Nubia, and high priest of Amen. Most significantly, he took on all the royal symbols as well. However, Ramses did not challenge this proclamation of a new dynasty in the south; he also didn't try to remove a Lower Egyptian governor named Smendes (also called Nesunebded) when he became just as powerful in the north. This may be the real meaning behind the legal documents that refer to part of the reign of Ramses XI as wehem-mesut, the "repeating of births."

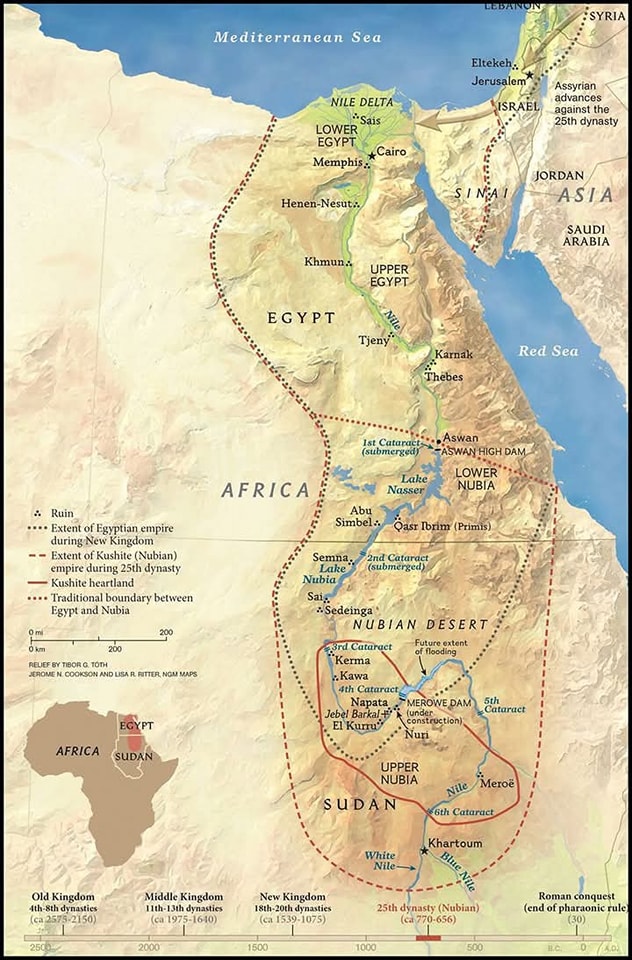

Abroad, both Mitanni and the Hittites, former enemies turned allies, had disappeared. Now a new Asian power, Assyria, was flexing its muscle as it moved into Syria and Lebanon, taking for itself the Levantine goods which had once supported the pharaohs' extravagant lifestyle. To the south, Egypt had lost Nubia, along with its valued products, for good. The end of the New Kingdom saw Egypt suffering from poverty, more corruption, usurpations, and anarchy in the delta. Egyptian ambassadors like the famous Wenamun were insulted by Asians who used to grovel when they heard the Egyptians were coming.

The Third Intermediate Period

For 2,000 years, the Egyptians had met and effectively dealt with war, famine, and every other crisis that came their way. Their civilization looked impervious to everything, including time. Nevertheless, under the Ramessids a series of factors worked together to start Egypt on a long, permanent decline. These factors were the loss of the empire, a steady shrinkage of the pharaoh's wealth and prestige, and the beginning of the Iron Age.(39) Most of these were problems the pharaohs couldn't solve--in fact, they happened so slowly that they may not have noticed while they were building monuments to their own glory--but with the advantage of hindsight we can see that Egypt's days as a great nation were ending.

From a political standpoint, when the XX dynasty ended, ancient Egypt began to die. The last Ramessid pharaohs didn't travel as much as their predecessors. In the past the king was expected to tour the realm every year, so that he could take part in important festivals; now he often sent a representative instead. Perhaps the need to keep the festivals made the Egyptians accept the existence of several rulers at the same time. As a result, scholars find this period of Egyptian history (dynasties XXI-XXV) very confusing, though plenty of contemporary artifacts exist. Third Intermediate Period (TIP) literature, for example, isn't much help, because religious texts are far more common than scrolls or inscriptions that contain historical data. In addition, most of the action was in the Nile delta, and we noted earlier that in the damp soil of Lower Egypt, fewer buildings, inscriptions and papyrus scrolls have survived. Only recently have we come to realize that the dynasties did not follow one another in linear progression, with only one "pharaoh" ruling; instead, like the other intermediate periods, there were different recognized kings in different parts of Egypt, with all five dynasties claiming to be in charge in the late eighth century B.C.! In the past, Egyptologists tended to overlook this era, because it wasn't as interesting as the New Kingdom, and they didn't even give it a name until Kenneth A. Kitchen wrote a book on it.(40)

With the disappearance of the Ramessids, Smendes and his commerce-minded descendents, the XXI dynasty, built a new capital for themselves, Tanis, in the northeastern delta, because the part of the Nile adjacent to Pi-Ramesse had dried up; they used stones and bricks taken from the XIX-XX dynasty capital. This used to confuse archaeologists like Pierre Montet (see below); when they saw statues of Ramses II at Tanis, they thought Tanis was the same place as Pi-Ramesse, not realizing that statues can be moved. The true location wasn't revealed until an Austrian archaeologist, Manfred Bietak, dug at the eastern delta site of Tell ed-Daba, where he found both Pi-Ramesse and the older city of Avaris. Meanwhile to the south, Herihor's descendants were kings in everything but name, ruling as high priests of Amen from Thebes.(41) The high priests who lived the longest, Pinedjem I and Menkheperre, did take royal titles for themselves, but all of them recognized the XXI dynasty as the ultimate human authority in the land. These two families kept the peace through diplomacy, with more than one marriage between them.(42)

When it comes to artifacts, some of the most interesting were discovered by Pierre Montet, a French archaeologist who excavated Tanis in 1939 and 1940. Under one corner of a temple he found three intact tombs containing ten XXI and XXII dynasty notables. Two of the mummies (those of pharaohs Psusennes I and Shoshenk II), had solid silver coffins, gold masks and a complete collection of jewelry. Although this sounds impressive, it does not compare favorably with Tutankhamen's treasures; when I got to see both the Tutankhamen and Tanite collections in the Cairo Museum, my first impression of the Tanite stuff was: "That's not so great."(43) Already the artwork is cruder than that of the New Kingdom, and the tombs are smaller than those enjoyed by the nobles of earlier eras. There is also evidence of corruption by the royal occupants; Psusennes' coffin was in a granite sarcophagus belonging to the XIX dynasty's Merneptah, while another sarcophagus came from a Middle Kingdom tomb; each of the canopic jars had somebody else's name on it; a lapis lazuli necklace on Psusennes was originally a gift from the Assyrians to Amenhotep III. It is hard to imagine how these rulers could arrange to have their mummies buried with stolen treasures, and expect to get away with it when facing Osiris in the final judgment. Maybe that is why the tombs were so small and carefully concealed; Psusennes and company didn't want to risk their bodies suffering the same fate they had inflicted on others.

This humble but harmonious picture grew more complicated when a Libyan named Shoshenk moved to Bubastis, in the eastern delta, and proclaimed himself pharaoh, becoming the founder of the XXII dynasty. The tribes of the western desert, called the Libu, Ma and Meshwesh in Egyptian records, were no longer a serious threat--Merneptah and Ramses III had seen to that--and Libyan prisoners captured in those wars were allowed to stay in Egypt, as slaves. In addition, individual Libyans had continued to settle in the western delta and the part of the Nile valley between Memphis and Heracleopolis, until immigration had made them a force to reckon with. However they got into Egypt, many became soldiers, and it looks like they gained control over the army gradually, allowing Shoshenk to assume power with a minimum of friction. In fact, members of Shoshenk's family had been priests to the god of Heracleopolis for several generations, so he may not have even looked like a foreigner. To make himself and his family more acceptable, he had his eldest son, Osorkon I, marry Maatkare, a XXI dynasty princess.

The XXII dynasty got off to a promising start. Like the founders of dynasties in other times and places, Shoshenk I consolidated his rule by putting relatives in several key positions. Osorkon I was not only his heir but also the dynasty's political chief, because he stayed at Bubastis. His second son, Iuput, went to Teudjai (a town eighty miles south of Memphis), where he assumed the following titles: governor of Upper Egypt, general, and high priest of Amen. Meanwhile in Thebes, the other high priests of Amen remained, but after this they were relegated to a supporting role. Shoshenk's third son, Nimlot, was stationed at Heracleopolis as another general. Djedptahefankh, a priest in Thebes who held the title "second prophet of Amen," may have been a fourth son of Shoshenk, suggesting that he was sent there to keep an eye on the Thebans.

Late in his reign, Shoshenk I led a successful campaign in Israel, which apparently saved the Israelites from the Syrians (we're assuming he was the mysterious "deliverer" mentioned in 2 Kings 13:5). Then at Thebes he began construction of the final gateway to the temple of Karnak, the so-called Bubasite Pylon, a structure so large that the pharaohs never finished it; on it he listed the names of more than fifty Asian towns that were now subject to him. For this reason, foreigners viewed the XXII dynasty as the most powerful family in Egypt; statues and scarabs of Shoshenk I and Osorkon I have been found as far away as Byblos, in Lebanon.

Shoshenk I was followed by a series of kings with barbaric-sounding names: Shoshenk, Osorkon, and Takelot.(44) Instead of going to war or building monuments, they stayed at home and stagnated. These kings tried to maintain their grip on the country by reserving important military, priestly and government jobs to relatives, or by giving their daughters in marriage to non-relatives in key positions. However, at the same time many officials, including the viziers, saw their powers decline, since they no longer had authority over all of Egypt. When royal princes were put in charge of distant cities, it weakened the dynasty rather than strengthened it; different branches of the royal family now competed to become the next heir to the throne in Bubastis, and they acted like independent monarchs when they didn't get it. Osorkon II, the fourth ruler of the dynasty, faced such a rebellion when Harsiese, his cousin in Thebes, proclaimed himself king. Fortunately for the north, Harsiese did not "rule" for long. The next official pharaoh, Takelot II, ruled from Heracleopolis instead of Bubastis. He tried to reunite the country under his immediate family by appointing his eldest son, Osorkon, as high priest in Thebes, while another son, Shoshenk III, took over in Bubastis. Instead, there was an embarrassing spectacle as Theban priests and officials ran Prince Osorkon out of town. Osorkon carved his version of the story on the Bubasite Pylon at Karnak, the so-called "Chronicle of Prince Osorkon," and it tells of an on-and-off struggle over who would rule in Thebes. Then in the first half of the eighth century B.C., power in Thebes went to a woman, the "God's Wife of Amen." By placing their daughters in that office, the XXII dynasty kings were able to still claim authority over the south, though after Takelot II such authority existed in name only.

Meanwhile in the north, Shoshenk III tried to nip another revolt in the bud by installing his brother Pedubast as "king" over Leontopolis, a city in the middle of the delta. Instead, Pedubast became the founder of the XXIII dynasty, as he and his successors didn't recognize the authority of the other Libyans anywhere. Meanwhile, more Libyans moved into the western delta, and their leaders were so uncivilized that they didn't even bother calling themselves kings; they used the older titles "Chief of the Ma" and "Chief of the Libu" instead. By 750 B.C., the cities of Heracleopolis and Hermopolis also became independent, ruled by distant relatives of Shoshenk III who weren't recognized as kings anywhere. With chaos increasing at home, Egypt's influence faded abroad, and in the end they did almost nothing to keep their Asian allies from falling to the Assyrians. The Assyrians, in fact, told others not to rely on Egypt, for it is "a broken reed, which pierces the hand that leans upon it." (Isaiah 36:6)

Around 730 B.C. a native Egyptian, Tefnakht of Sais, raised the standard of revolt against both the Libyans and the priests. He and his son Bakenranef (Bocchoris) are listed as the XXIV dynasty, which briefly ruled the western half of the Nile delta and Middle Egypt until 715. They fell to invaders from the south, who, like the Libyans, had become so Egyptianized that they were no strangers to Egypt. In fact, they were Egypt's former slaves--the Nubians.

While Egypt was breaking up, Kush had re-established itself as a unified state, run not by an Egyptian governor like Panehsy, but by a Nubian named Alara. Not long after that, Alara's brother and heir, Kashta (760-747), marched to Aswan and set up a stone declaring himself the king of Upper and Lower Egypt. Although he may have continued north to visit the temples and priests of Thebes, Kashta made no attempt to enforce his rule on Egypt proper, and afterwards returned to Napata, his capital. To the south, he expanded the frontier to the edge of sub-Saharan Africa, finally stopping near the modern town of Kusti, Sudan. Kashta's son Piankhy (747-716, also spelled Piye) completed the task his father had started, by conquering Egypt and proclaiming himself the first pharaoh of the XXV dynasty.

Early in his reign, Piankhy got his sister Amenirdis installed in Thebes, as the "God's Wife of Amen." This allowed Piankhy to claim he was the real pharaoh; he also expressed a desire to celebrate the ancient Opet festival at Thebes. In 728 he assembled an army and marched north to enforce his authority on Upper Egypt. He may have done this because Tefnakht was marching south, and the priests of Thebes called on Piankhy to save them. The Nubians were faster, getting all the way to Hermopolis before meeting any significant resistance. After a siege lasting several weeks, which saw the participation of both Piankhy and Tefnakht, Piankhy prevailed. The princes of Hermopolis and Heracleopolis submitted to Piankhy, and he continued downstream to Memphis and Heliopolis, where he paid his respects to the ancient gods and received the homage of the delta rulers. Because the Nubians practiced the Egyptian religion and kept Egyptian customs more faithfully than the Egyptians were doing, Piankhy came to represent an older, more orthodox Egypt. In his inscriptions he told everybody that his dynasty was morally upright, and had come to liberate Egypt from the degenerate, worldly, lax and impious kings of recent years.

Piankhy didn't like killing, even in wartime, and pardoned those former enemies who swore loyalty. However, he also had a soft spot for horses, and saw red when somebody mistreated them. When he had captured the palace of King Nimlot of Hermopolis, he toured the stables and found the horses had been neglected. In the victory stele he left at Napata, Piankhy describes this unforgivable sin: "His Majesty proceeded to the stable of the horses and the quarters of the foals. When he saw they had been left to hunger he said to his submissive foe, 'I swear, as Ra loves me, as my nose is refreshed by life: that my horses were made to hunger pains me more than any other crime you committed in your recklessness!'"

Piankhy was buried in a steep-sided pyramid, a few miles from Napata; his horses got a cemetery nearby, and were buried standing up and dressed in their finest, ready to serve their king in the afterlife. Eventually, the Nubians built more pyramids than the Egyptians did, but they don't get as much attention, because fewer tourists go to the Sudan and because they are smaller than those of Giza and Saqqara (the largest, that of Taharqa, originally stood 165 feet high). The next three black pharaohs, Shabaka, Shebitku (also called Shabataka) and Taharqa (the Biblical Tirhakah), consolidated Nubian rule over Egypt. However, the only local kinglet they removed was Bakenranef, replacing him with a Nubian governor. Thus, to outsiders like the Assyrians, Egypt was really a confederation, with the chief of each city a de facto king.

The triumph of Kush was short-lived. While the Nubians had made themselves masters of Egypt, the all-conquering Assyrians had made themselves masters of the Middle East. As the Assyrians got closer, the Nubians unwisely tried to form anti-Assyrian alliances with the Phoenicians, Philistines and Israelites. In 702 B.C. the Assyrian king Sennacherib struck back, advancing across the Sinai peninsula to Pelusium, and inflicting a defeat that ended whatever dreams the Nubians had of ruling Asia. Sennacherib's son, Esarhaddon, responded to a second provocation by taking Memphis in 671 B.C.; Taharqa was wounded and forced to abandon Egypt. However, two years later Taharqa came back for a rematch and recovered Memphis; Esarhaddon died on the way to Egypt, so a proper Assyrian response was delayed until his son Ashurbanipal was crowned at Nineveh, the Assyrian capital. He arrived in 667 B.C., defeated Taharqa again, and chased him all the way to Thebes before turning back. This wasn't the end of the matter, though, because as soon as the fighting was over, the local "kings" and governors started plotting to bring Taharqa back. Ashurbanipal arrested the whole lot, took them to Nineveh, and put them to death except for Necho of Sais, who may have been descended from the XXIV dynasty rulers. Because Necho was the only native they could trust, he now became the governor of all Egypt. Thus, the Assyrians extinguished dynasties XXI-XXIII, reunited Egypt and ended the political confusion that marks the Third Intermediate Period.

But Necho I didn't have time to accomplish anything else. In 664 B.C. Taharqa was succeeded by his son-in-law Tanwetamani, and he decided to try his luck with the Assyrians. He marched north, killed Necho and captured Memphis, only to fall back to Thebes when he heard that Ashurbanipal was coming. This time Ashurbanipal showed no mercy; he destroyed Thebes so completely that it never became an important city again. After that the Nubian kings stayed at home, though the priests of Thebes continued to call Tanwetamani their lord as late as 656 B.C.(45)

This is the End of Chapter 2.

FOOTNOTES

35. The XIX dynasty rulers worshipped Set, as one might guess from Seti's name; at Avaris/Pi-Ramesse he restored the Set-temple that the Hyksos had founded, four hundred years earlier (see footnote #20). However, as we saw earlier, Set was the villain of the Osiris myth, and because of that, Set had fallen out of favor over the centuries, so Seti had to give Set's enemies equal time. In the hieroglyphics on the monuments Seti built, his name is mentioned many times, of course, but for the three most important monuments (the Osiris temple complex at Abydos, his mortuary temple, and his tomb), the stonecutters altered Seti's name slightly, so that whoever read the name out loud would not accidentally cast a spell that could summon Set!

36. In 1987, American Egyptologist Kent Weeks discovered a giant tomb in the Valley of the Kings, about 100 yards from Tutankhamen's, where as many as 52 sons of Ramses II may have been buried together. Because of the careful work required by modern archaeology, and logistical problems like clearing out all the rubble and preventing cave-ins, he has been working on the tomb ever since, and it looks like it will take a century to excavate it completely. You can follow Weeks and other activities in the valley on his website, the Theban Mapping Project. He believes that Ramses was the Pharaoh of the Exodus, so he is looking for evidence of the Biblical story here, as well as trying to find out why Ramses gave so many princes a communal burial (no other pharaoh on record did this). I think this was a make-work project; Ramses lived twenty-six years after his own tomb was finished, meaning that for decades the valley's tomb-builders had a hard time finding enough work to keep themselves fully employed.

Even when he was building monuments for others, Ramses had to show off. Next to his temple at Abu Simbel (see also Chapter 8, footnote #16), he built a smaller temple for his favorite queen, Nefertari. Few queens got temples, especially when they were alive, so this was exceptional treatment. Still, at the temple's entrance Ramses put two statues of Nefertari, flanked by four of himself!

Despite all this, Nefertari soon disappeared from Egyptian records, leading us to believe she died less than a year after Abu Simbel was completed. Ramses went on to build a lavishly painted tomb for her, but it was left to his second wife, Istnofret, to perform the most important queenly duty; her son, Merneptah, became the next pharaoh.

Istnofret had another son we know something about, Khaemwaset. He was crown prince from the 50th to 55th year of his father's reign, but then he died and Merneptah took his place. Ramses also appointed him high priest of Memphis; in that job he restored pyramids and other ancient monuments in the neighborhood of the former capital, quarried stone for Ramses' building projects from other monuments, and founded the Serapeum, the tomb for sacred bulls. Because of these activities, Khaemwaset was buried in the Serapeum, instead of with his brothers.

37. Although the New Kingdom pharaohs never failed to report glorious victories, note that each dynasty's triumphs took place closer to home than those of its predecessor. While the XVIII dynasty devoted most of its military energy to Syria, the XX dynasty fought defensive battles in the heart of Lower Egypt, and depended on foreign troops to win. Read Chapter 3 of my Middle Eastern history for more about the Sea Peoples and the campaigns of Ramses III.

38. By the XXI dynasty nearly all of the tombs in the Valley of the Kings had been stripped of their treasures. The priests who ruled Thebes at this time rescued and rewrapped forty royal mummies, and moved them to a tomb in the cliffs behind Queen Hatshepsut's Deir el-Bahri temple. Then the priests buried several members of their own family in the tomb, sealed it up, and forgot about the place. We believe one of the high priests of Thebes, Pinedjem II, was the original owner of the tomb, before all these royal "guests" joined him. This bizarre cache was rediscovered in the mid-nineteenth century, by descendants of the ancient robbers. Thirteen more "wandering mummies" were relocated to the tomb of Amenhotep II, which had escaped plundering up to that point.

Another mummy, believed to have come from the Deir el-Bahri cache in 1860, ended up in a Canadian museum, in a room full of exhibits devoted to sideshow freaks. In 1999 it was sold to a museum in Atlanta, Georgia, identified as Ramses I, and subsequently sent back to Egypt. I have a feeling that the mummy's lengthy stay with so many other pharaohs in somebody else's tomb, the journey to North America by steamship, the place where it resided for 139 years, and the return trip on Delta Airlines, were all experiences that the pharaoh couldn't have imagined when he was alive!

39. Because it lacked iron, Egypt was handicapped when other nations--like the Hittites, Philistines and Assyrians--switched from bronze to iron weapons. The iron dagger found on Tutankhamen's mummy was probably a gift from the Middle East, either from Mitanni or the Hittites. One of the previously mentioned Amarna letters, from King Tushratta of Mitanni to Amenhotep III, describes an iron dagger that was sent as a gift, and it sounds an awful lot like this one.

Incidentally, the dagger was subjected to spectrocopic analysis in 2016, and it was found to contain significant traces of nickel and cobalt. In nature, these three metals are only found together in meteorites. If the ancients knew that the iron in the dagger came from a rock that fell from the sky, it would have meant a lot to them.

40. Kitchen, K.A., The Third Intermediate Period of Egypt (1100-650 B.C.), Warminster, UK, Aris & Phillips Ltd., 1973.

41. Upper Egypt now became a complete theocracy, with the decrees of the high priest often appearing as oracular pronouncements. Following Herihor's example, the high priest was usually a military commander as well. During this period Egyptian religion may have looked monotheistic, as the older gods were now rarely even mentioned; their attributes were transferred to Amen-Ra. However, this wasn't a revolution in the sense of what Akhenaten tried. The other gods were not rejected, but simply ignored. We call it henotheism when a religion allows many gods, but one supreme deity gets all the power and attention, which is the case here.

42. Smendes may have been Herihor's son. If this is true, then one family, not two, was ruling in Tanis and Thebes. It also helps explain why these kings and priests got along so well.

43. Another pharaoh buried at Tanis was Amenemopet, the son of Psusennes I. His burial wasn't as splendid as his father's; instead of a solid gold funerary mask, he got one made of cartonnage, a form of paper mache, with a very thin layer of gilding on the outside to make it look like the masks of Psusennes and Tutankhamen. Furthermore, it only covered his face, not the whole head. This tells us that during the second half of the XXI dynasty, Egypt was running out of gold.

44. The Libyan pharaohs may have looked and acted like Egyptians at this stage, but they didn't forget their ancestry. Likewise, the Nubian pharaohs who followed them worshiped Egyptian gods and wore Egyptian dress, but their crowns had two cobras over the forehead instead of one.

45. Besides the kings, the most powerful man in Upper Egypt at this time was Mentuemhat, the mayor of Thebes from about 670 to 648 B.C. For himself the highest title he claimed was "Fourth Prophet of Amen-Ra," but from Hermopolis to Aswan he commissioned monumental building projects, prompting Assyria's Ashurbanipal to call him "Mantimanhe, king of Thebes." Though married to a princess from Napata, Mentuemhat was also a true opportunist, switching allegiance from Taharqa to Ashurbanipal to Psammetich, serving whomever did the most for Upper Egypt. His tomb at Deir el-Bahri is the largest ever built in ancient Egypt for a non-royal person.

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A History of Africa

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|