| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

A Concise History of Korea and Japan

Chapter 5: Northeast Asia Today

Korea since 1953, Japan since 1945

This history paper covers the following topics:

| Japan, Incorporated | |

| South Korea: Growing Pains | |

| Japan's Lost Decades | |

| South Korea: The Sixth Time is the Charm | |

| The Bizarre Land of North Korea | |

| Go to Page Navigator |

Japan, Incorporated

The terms of the armistice took all territory outside the four main islands away from Japan and completely demilitarized what was left. Key wartime military leaders were placed on trial, and General Tojo, along with six colleagues, was executed.(1) Other militarist governmental and business leaders were blocked from postwar activities. For a while, industries were dismantled for reparations, but this practice was soon stopped.

In return, the Allies gave aid to rebuild the shattered economy, while insisting on democratic institutions in the government and society. The new education system was based on the American pattern of decentralized public schools, with textbooks rewritten to delete militant nationalism. A land reform policy intended to reduce tenancy and absentee landlordism was introduced. Unions gained the right of collective bargaining, and their membership grew rapidly.

Before World War II ended relations between the United States and the Soviet Union deteriorated, so US President Harry Truman decided that the American military occupation of Japan would be shared with no other country. What this meant was that Japan would not suffer the division that fell upon Germany and Korea. Another bit of good luck for the Japanese was that few Americans were familiar with Japan's language and culture, forcing MacArthur and his staff to rely on native advisors and institutions most of the time.(2) This meant that the military occupation was more lenient than expected, and the Japanese had a major say in what form their country would take. Of course the armed forces were completely disarmed and 90% of the government was fired, but the new inexperienced public servants regularly made visits to their purged predecessors for advice, allowing many prewar institutions to survive more or less intact. America ordered the breakup of the Zaibatsu combines to permit free enterprise, but they managed to pull themselves together again; employees of the new companies bought stock in other companies that used to be part of the same combine, and later they merged together to form the largest of modern Japan's corporations.

A new constitution, drafted in consultation with the Americans, went into effect in May 1947. It set up a democratic, two-house parliamentary-cabinet system in which the majority party selected the prime minister. Sovereignty rested in the people; the emperor, forced to renounce his divinity, was referred to as "the symbol of state." No limitations were placed on voting because of income or sex. War was renounced as a sovereign right and "land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential will never be maintained."(3) A peace treaty between Japan and the Western Allies (but not with the USSR) was signed on September 8, 1951; seven months later the last American soldiers departed and Japan regained its independence. A security pact between Japan and the United States allowed American troops to be stationed in Japan.(4)

Since independence, conservatives have controlled the Japanese government most of the time (1952-1993, 1996-2009, and 2012-present).(5) In 1955 two conservative parties merged to form the Liberal Democratic party (LDP), which despite the name, was also right-wing. The LDP's platform promoted friendship with the West, especially the United States, and modest rearmament. Based on professional civil servants and business interests, it was sufficiently strong to endure periodic charges of corruption. Changes in LDP leadership, though frequent, were handled through negotiations among the Liberal Democratic elite, not directly as a result of shifts in voter preference. At first the main opposition came from the Japan Socialist Party, forerunner of today's Social Democratic Party; it demanded nationalization of industry, opposed the security pact with the United States, and favored neutrality in foreign affairs. The small Communist party was vocal but weak.

The new system was flexible enough to absorb the radical transformation Japan experienced in the late twentieth century. Rapid urbanization posed the greatest challenges. Rural areas lost population while city populations skyrocketed. With more than 11 million people, Tokyo became the largest urban area in the world (until Shanghai and Mexico City caught up). Three great concentrations of industry and population clustered around Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya; they occupy only 1 percent of the country's land area but contain over one-fourth of the country's population.

The economic growth of Japan in the years from 1952 to 1990 was every bit as impressive as the growth of the Meiji era. Annual economic growth regularly reached at least 10 percent from the mid-1950s to the early 1980s, higher than the growth rate of every other nation. By 1968 Japan's GDP was the third largest in the world, exceeded only by the USA and USSR; in 1986 Japan moved ahead of the Soviet Union as well, to take the number two position. Many have sought to explain the Japanese miracle, and it is likely that all of the reasons cited below are responsible:

1. The special spirit and skill of the Japanese people, which included the world's highest rate of savings and investment. Often traditional values were applied to modern life; for example, A Book of Five Rings, a 17th-century tactics manual written by the great samurai Miyamoto Musashi, is widely read by today's businessmen. The logo "Made in Japan" meant junk in the mid-twentieth century, but since then it has been a symbol of quality production. Also important was the Japanese emphasis on cooperation within the corporation, and the positive role the company can play in the employee's non-working life; both of these attitudes are carryovers from the feudal era. Many companies hired employees for life, and provided affordable apartments for them; employees often traveled together in groups on vacations and even honeymoons. Few days were lost to strikes, social activities promoted and expressed group loyalty (including group exercise sessions before the start of the working day), and managers displayed active interest in suggestions by employees. Psychiatrists reported far fewer problems of loneliness and individual alienation than in the West, because of the Japanese devotion to group activities.

2. Very low government expenditures in social services and defense, thanks to US protection. When Japan became rich enough to challenge the US economically, most Japanese were reluctant to make their country a superpower in anything but economic terms; that kept defense spending down, too.

3. A plentiful supply of cheap yet skilled labor during the immediate postwar years.

4. Large amounts of American investment in the 1950s and 60s, and the ready availability of American technological know-how, eliminating the need to conduct much research locally.

5. A continuing emphasis on education. The extensive school system of previous eras was further expanded, giving many more Japanese the chance to attend secondary schools and universities, which in turn were strongly oriented toward technical subjects. Japanese children were encouraged to achieve academic success, with college entrance exams that were so demanding that preparation for them became a major part of a young person's life. The scientific and technical focus encouraged strong emphasis on rational inquiry and practical knowledge. The impact of this cultural focus showed as Japan began to generate discoveries and inventions of its own, instead of cleverly imitating ideas developed elsewhere, as well as in the unusually high I.Q. scores of Japanese children. But the tendency toward conformity stayed in the picture, with disciplined memorization counting for more than individual achievement. For example, in the mid-1980s the government, appalled to discover that a majority of Japanese children did not eat with chopsticks (they used knives and forks in order to eat more rapidly), invested considerable money to promote chopstick training in the schools!

6. Far fewer legal restrictions on economic growth than most industrialized countries have. There nation has few lawyers, for people were expected to always try to reach solutions that will benefit everybody the most, and they would make and abide by their agreements without the enforcement of a third party.

Japan faced serious obstacles on the road to prosperity. It had to import much of the food for its population,vwhich now surpassed 100 million, and most of the raw materials for its industries. The Korean war gave Japan an initial boost, as the American troops made large purchases. The 1973 oil embargo and subsequent price increases by all of the OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) nations severely affected Japan. Inflation skyrocketed, economic growth plunged, and for a while the balance of trade was negative.

Japan's business managers made the necessary adjustments for recovery. By the end of the 1970s the Japanese built half the world's tonnage in shipping and had become the world's biggest producer of motorcycles, bicycles, transistor radios, and sewing machines. The Japanese soon outpaced the United States in automobile production and drove the American domestic television industry virtually out of business. By the 1990s, Japan's per capita income was nearly $22,000, compared to the U.S. per capita income of $19,800. After the October 1987 US stock market slide, Tokyo became the world financial center, dominating banking.(6)

Increasing economic success at home provided new opportunities in foreign relations. Many nations both in the West and Asia resented Japanese competition and the Japanese reluctance to open their own markets to outside goods.(7) Calls for retaliation by erecting tariff barriers against Japan were a recurrent threat, and the Japanese responded by increasing their economic aid to developing nations and by investing directly in the United States and Europe. Since the 1980s only the US has given more foreign aid. In 1950 the United States was the world's greatest creditor nation, and Japan was the world's greatest debtor nation; forty years later the US national debt reversed those roles exactly. At the same time, Japan let in more Western culture, but except for interior decorations and films, what the Japanese gave back was negligible; this was not where national creativity showed an international face.

But not all of the changes wrought on Japanese society by progress have been good. The average Japanese worker is expected to be a workaholic, and some have literally dropped dead on the job from heart attacks or other stress-related illnesses. Personal consumer standards did not rise as rapidly as national output did, because of the concentration on savings and the government-sponsored push to promote exports rather than drain output toward internal use. Leisure life remained meager by Western standards, and many Japanese were even reluctant to take regular vacations. The shutting out of foreign-grown foodstuffs and manufactured goods caused prices to climb until Japan became one of the most expensive places to live in the world. For example, a $100 watermelon was considered overpriced until $125 ones appeared on the market. Stock and real estate prices were inflated most of all, in an economic trend now called the Japanese Asset Price Bubble. At the bubble's peak in 1990, a typical 675 sq. ft. house cost $432,000, and the owner's children or grandchildren were expected to finish paying off the mortgage; it was estimated that the real estate of Japan, a country about the size of California, had a combined value four times as great as that of the whole continental United States!

In the late 1980s the Japanese watched uneasily as South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore (together called "the Four Dragons" of the Pacific Rim) used the Japanese model of a strong and disciplined work force and efficient use of new technology to become effective competitors in the world market. South Korea especially launched a direct challenge to Japan in the manufacturing of computers and automobiles.

South Korea: Growing Pains

For more than thirty years after the Korean War, South Korea experienced political problems. But at the same time, the economy boomed, making South Korea an Asian success story like Japan and Taiwan. This came about because the South Korean government has always made economic growth its priority, especially in foreign trade. At first South Korea only traded with other non-communist countries, but after the Cold War ended there was a second wave of dramatic expansion, as trade opened up with China, Russia, and the nations of Eastern Europe. In 2007 South Korea's gross domestic product caught up with and passed that of Canada, one of the original G-7 nations; by 2013, South Korea's GDP was running at $1.3 trillion.

Much of South Korea's success came from imitating the Japanese model, though in this case the Koreans had to start from a much lower base, due to the Korean War and Japanese exploitation leaving it dirt poor. Huge industrial firms were created by a combination of government aid and active entrepreneurship. Exports were actively encouraged and by the 1970s, when Korean growth rates began to match those of Japan, Korea began to compete successfully with cheap consumer goods and automobiles. They did even better than Japan when it came to steel production, while the Korean textile industry erased almost one-third of the Japan's textile-related jobs.

Huge industrial groups like Samsung, Daewoo and Hyundai were modeled after the great prewar Japanese Zaibatsu holding companies, and likewise wielded great political influence. Hyundai, for example, is the creation of the entrepreneur Chung Ju Yung, a modern folk hero who walked 150 miles from his native village to Seoul to take his first job as a day laborer at the age of 16. By the 1980s, when Chung was in his sixties, his firm had 135,000 employees and embraced 42 overseas offices throughout the world. Hyundai acts like a second government along Korea's southeast coast. It builds ships, including petroleum supertankers; thousands of housing units were constructed and given to relatively low-paid workers at below-market rates; it built schools, a technical college, and an arena to practice the traditional Korean martial art, Tae Kwon Do. With their lives carefully provided for, Hyundai workers respond in kind, putting in six-day weeks with three vacation days per year and participating in almost-worshipful ceremonies when a fleet of cars is shipped abroad or a new tanker launched.

The Daewoo shipyard in the 1980s.

South Korea's rapid entry into the ranks of newly industrialized countries produced a host of other changes. Population growth soared, until we got the figure cited at the beginning of Chapter 1: 51 million people in a nation the size of Indiana. One fourth of this population is crammed into the city of Seoul, which helps to explain why even with their prosperity, some Koreans have emigrated, and the government now encourages birth control.(8) Per capita income advanced to $33,000 a year, close behind that of Japan's, and even the poor are considerably better off than the poor of developing countries.

In the years after the war South Korea's first president, Syngman Rhee, came to see his opponents as communist agents, and under him the government changed from a democracy to a dictatorship. When Rhee won his fourth presidential election in 1960, the opposition parties cried foul, and anti-government demonstrations/riots got so bad that Rhee resigned and went into exile at Honolulu, Hawaii, for the rest of his life. The constitution was rewritten and a "Second Republic of Korea" was proclaimed, but it only lasted for eight months. The new president, Yun Posun, lost his power when General Park Chung Hee seized it in a 1961 coup, but held the presidency for one more year before resigning.(9)

Park Chung Hee legitimized his rule by getting elected president in 1963, and did much to repair the economy, but rising protests against his authoritarian rule led to the imposition of martial law in 1972. In 1975 all political opposition was banned. So far Park has been the longest-lasting head of state in South Korean history, but all things made by man must come to an end, and his regime ended with his assassination by the head of the Korean Central Intelligence Agency in 1979. Premier Choi Kyu Hah was then elected president in his place, but before 1979 was over, he was ousted in a coup led by General Chun Doo Hwan.

Another round of martial law followed, and in May 1980 protests against the lack of human rights led to an uprising in Gwangju that was harshly suppressed by the army; an estimated 241 people were killed in the crackdown. Between August 1980 and January 1981, some 60,000 were arrested without proper warrants and sentenced to hard labor in the Samchung Re-education Camp. Another constitution was approved in October 1980, and Chun became president in 1981. However, his army-backed Democratic Justice Party (DJP) lost seats in the 1985 legislative elections, and in June 1987 the worst political protests since 1980 erupted. The crisis was defused by the writing of yet another constitution, the sixth (and the most recent) so far. According to it, the president would only be allowed to serve a single five-year term; it also curtailed presidential powers, strengthened the legislature, and pledged military neutrality in politics.

Japan's Lost Decades

Emperor Hirohito died on January 7, 1989 and was succeeded by his son Akihito, who is still emperor at the time of this writing. Akihito's reign has been called the Heisei era, which officially means "peace everywhere." The Heisei era coincided with a long-term swing in the economy. After one more good year, the Nikkei 225, the chief index of the Japanese stock market, hit its all-time high on December 29, 1989, and then entered a slump from which it has not recovered, more than a quarter century later.

In the previous section on Japan we noted that the economy swelled to unsustainable levels in the late 1980s. The economic bubble burst when the world was hit by a major recession in 1990. In the case of Japan it was a depression, with the Nikkei losing half its value by 1991. A round of deflation set in, starting with those overinflated property values; by 1996 Tokyo land prices were only 20 percent of what they had been just a few years earlier, and they still hadn't bottomed out yet. As land prices plummeted, bank balance sheets were devastated; everyone and every company that owned real estate saw their wealth vanish.(10)

Japan managed to keep the unemployment rate from going above 3.2% for most of the 1990s, and it peaked at 5.5% in 2009, but even these are record highs. These figures do not include workers who have stopped looking for jobs, those with part-time or temporary jobs who would rather work full-time, and those with jobs who aren't really working. Companies tried to ease the pain of recession by keeping the middle-aged family breadwinners on the payroll, often as "window side employees" who are paid to sit at a desk and do almost nothing at all. Even so, there were layoffs in a land that had never experienced them before--most often among women and younger employees. Younger workers grew resentful that they bore the brunt of the recession, compared with workers who were retained simply because they had entered the work force before 1990.

As the twenty-first century began, Japan remained in a state of stagnation, long after economic recovery came to the United States and Europe. Japanese referred to the 1990s as the "Lost Decade," until it became apparent that it would take more than one decade to recover. In 2011, the Chinese GDP pulled ahead of the Japanese GDP, so now the People's Republic, instead of Japan, has the world's second largest economy.(11) Abroad, foreign articles and books no longer praise Japan's economy, education system, or Tokyo's policy of micro managing business, and the world has stopped following the Japanese example.

Being on a geologic fault, Japan has always been earthquake-prone. A major tremor struck the city of Kobe in 1995; 6,000 were killed, 44,000 were injured, and a quarter million houses were wrecked or burned. Even worse was the triple play nature inflicted on northeastern Honshu in March 2011; first a magnitude-9 earthquake, which generated a tsunami, and the tsunami caused a partial meltdown of the Fukushima Nuclear plant (the worst radiation disaster since the Chernobyl meltdown in 1986). The only community in the area to escape damage was the village of Fudai, because back in the 1970s, a mayor obsessed with tsunamis built a 51-foot-high seawall and floodgate to protect the village. Japan has been the most technologically advanced country in Asia since the Meiji Restoration (see Chapter 3), but such a disaster is a reminder that even today, nature is still stronger than man.

The ups and downs of the Japanese economy have been accompanied by drastic changes in traditional values and attitudes. Parental authority and family ties weakened as young married couples, forsaking the traditional three-generation household, set up their own homes. The strains of urbanization were reflected in a serious problem with pollution, student riots and in the appearance, for the first time in Japanese history, of juvenile delinquency. Western influence--seen in punk haircuts, fashions, television, sports, and beauty contests and heard in rock music--clashed with the traditional culture. Most disturbing are a series of religious cults that claim to have the answers the disillusioned are seeking.(12)

Perhaps the greatest changes are those affecting women. Before World War II there was little opportunity for Japanese women outside the family. After 1945 they gained the right to own property, sue for divorce, and pursue educational opportunities. By the end of the 1980s, women constituted nearly 50 percent of the nation's work force, and more than 30 percent of women attend post-secondary schools. On top of that, many women are not in a hurry to get married, though they live in a society that calls spinsters "Christmas cookies," because "nobody wants her after the 25th." The changing status of women is best symbolized by Masako Owada, who married Crown Prince Naruhito in 1993; before she joined one of the world's most tradition-bound families, she was an officer in the Foreign Ministry, acting very much like the career women of the West.

Finally, changes in demographics may be part of the reason why the economy hasn't bounced back, and those changes are likely to affect Japan for decades to come. In the first decade of the twenty-first century, Japan had the longest life expectancy of any nation (81.25 years), thanks to its first-rate technology and health care system. The population leveled off at 128,083,960 in 2008, and since then has slipped into a decline. Like the former Soviet Union and much of Europe, Japan no longer has enough births and immigrants to replace the people it loses every year. Falling birthrates are a worldwide trend, due to later marriages, birth control, going to school longer, smaller living quarters in the cities, and so on. In the case of Japan, psychological overcrowding has also been cited as a factor, along with reports that the average Japanese couple is too busy working to have much interest in babies or sex. And at the same time the median age is rising, which means trouble in the future for the following reasons:

- It becomes harder to support social service programs, when there are fewer young people for every senior citizen. No government program has yet been developed that will work in such a situation.

- It is difficult, if not impossible, to stop the shrinking of a population, when a large portion of it is too old to have babies.

South Korea: The Sixth Time is the Charm

Gangnam, Seoul's fanciest district, seen from the Samsung headquarters at night. When UN Tanks drove through here, during the Korean War, there was nothing but rice paddies to get in the way. Much of what you see now was only built after the 1988 Olympic Games.

Roh Tae Woo, Chun Doo Hwan's successor as head of the DJP, reached an agreement with opposition leaders Kim Dae Jung and Kim Young Sam in September 1987 for the writing of South Korea's sixth constitution. This constitution has been the most successful to date; both it and the Sixth Republic it produced are still going strong, and it appears to have solved South Korea's political problems. Then new elections were held on December 20, 1987; Roh won with only 37 percent of the vote because the opposition was divided. He took office on February 25, 1988, and legislative elections took place the following April; this time three opposition parties won 164 of the 299 seats. In November former president Chun apologized to the nation for abuses of power by his regime. The DJP merged with two of the opposition parties in 1990 to form a new majority party, the Democratic Liberal Party (DLP), and it captured 149 of 299 seats in the March 1992 legislative elections.

The summer Olympic Games of 1988 were held in Seoul, a sign of South Korea's progress and a source of great national satisfaction. During the games, Korean nationalism flared against American athletes and television commentators, based on real or imagined tendencies to seek out faults in Korean society. South Korea, like Japan, continues to look heavily toward Western markets and United States military assistance, but there is clearly a desire to put the relationship on a more equal footing.

Former dissident Kim Young Sam, the first DLP presidential candidate, won the December 1992 presidential election and assumed office two months later, becoming the first nonmilitary president of South Korea in more than three decades. When it came to restoring democracy, Kim showed he meant business; in 1995 he jailed both of his predecessors. Chun Doo Hwan was charged with the slaughter of the protesters in the 1980 Gwangju uprising, while Roh Tae Woo was accused of taking $369 million in bribes from 35 businessmen.(13)

The 1997 economic crisis of Thailand spread to South Korea late in that year, when investors lost confidence in the debt-laden economy, causing the South Korean currency to rapidly lose its value. This devaluation made Seoul's foreign currency reserves disappear, threatening the capacity of the government, banks, and industries to repay foreign debts; meanwhile the unemployment rate soared as unstable businesses declared bankruptcy. The government accepted one of the largest aid packages ever arranged with the United Nations' International Monetary Fund (IMF), bringing in an $18 billion shot in the arm. The agreement, however, required South Korea to sharply reduce public spending, and increase taxes and interest rates. The economic crisis ended a year later, but it still influenced the 1998 presidential election, in which the voters elected Kim Dae Jung as the next president. Kim Dae Jung has been called the "Nelson Mandela of Asia" for being Korea's most famous opposition leader and pro-democracy advocate; he opposed the military regime in Seoul as far back as the 1960s, and was under a death sentence in 1980. If anybody had any doubts about democracy finally coming to South Korea, they were dispelled by Kim's election.

Both South Korea and North Korea became members of the United Nations in 1991. In December, the two signed a landmark treaty of reconciliation and non-aggression. Because North Korea had started working on developing nuclear weapons, talks continued after the signing of a 1992 accord laying the framework for post-cold-war trade between the two countries; however, North Korea refused to allow foreign monitoring of its nuclear power plants. In June 2000 the two Koreas held the first face-to-face meeting between their presidents; Kim Dae Jung went to Pyongyang, where he got along better than expected with Kim Jong Il. For this Kim Dae Jung received the Nobel Peace Prize in the same year. However, this achievement didn't look so great when it was later revealed that Kim Dae Jung had given North Korea $500 million before the summit meeting took place. Because North Korea did not honor the agreements reached, both the US and South Korea decided that North Korea could not be trusted, so support for this peace process faded as the twenty-first century began (US President Bush listed North Korea as one of the three countries in the "Axis of Evil," along with Iran and Iraq.). On a brighter note, the 2002 FIFA World Cup, co-hosted with Japan, was celebrated by millions as a major cultural event (see Chapter 2, footnote #15).

Ban Ki-moon, a South Korean career diplomat, was Secretary General of the United Nations from 2007 to 2016.

The election of Roh Moo-hyun, a former labor and human rights lawyer, to the presidency in 2002 was seen as the passing of leadership to the next generation, because at age 56, he was twenty-two years younger than Kim Dae Jung. Roh's administration initially promised "participation government," but instead decided to take a long-term view and execute market-based reforms at a gradual pace, which was unpopular with the public. Although South Korea launched a high-speed train system, KTX, and the stock market continued to do well, youth unemployment rates were high, real estate prices skyrocketed and the overall economy lagged.(14) In March 2004, the National Assembly voted to impeach Roh on charges of corruption and the breaking of election laws, but Roh's party won the parliamentary elections held the following month, so the Constitutional Court overturned the verdict and reinstated him. The second half of Roh's term saw labor unrest, a feud between Roh and the media, and some diplomatic friction with the United States and Japan, at a time when good relations with both were needed to keep the North Korean nuclear threat in check. After Roh Moo-hyun left office, in April 2009, he and his family were investigated again for bribery and corruption. That ended on May 23, 2009, when Roh committed suicide by jumping off a cliff near his home.

Roh's successor, Lee Myung-bak, had previously been the CEO of Hyundai and mayor of Seoul. He served as president from 2008 to 2013, and overall was more successful, in part because he seemed to have a program for everything. For the economy, Lee announced the "747 Plan," which promised: 7% annual growth, a per capita income of $40,000, and the world's seventh largest economy. He also talked about digging the "Grand Korean Waterway," a canal that would go across the country, connecting Seoul with Busan, but concerns by critics over the cost and the effect on the environment kept the project from ever getting started. A reshuffling of the Cabinet, combined with several reforms and deregulating measures, allowed the country to recover quickly from the worldwide recession that struck in 2008, and allowed Seoul to host the G20 summit in 2010. Regarding foreign policy, Lee took a tougher stand with North Korea, while mending strained relations with the United States, China and Japan. One by-product of this was that Lee lifted the ban on imports of beef from the United States, which caused massive protests for two months from people fearing outbreaks of mad cow disease.

In February 2013 the current president, Park Geun-hye, was inaugurated, as South Korea's first woman president and the first female head of state in Northeast Asia since ancient times. Park is so stranger to politics; she is the daughter of former president Park Chung Hee and served as first lady from 1974 to 1979, after a North Korean assassin shot at her father and killed her mother instead. Unmarried when elected, Park explained it by saying she is "married" to her nation. So far she has promised a "new era" of government and that she would be a "president for the people." She is also making what may be the last call for peaceful reunification of the Korean peninsula; younger South Koreans aren't very interested in uniting with North Korea, viewing such a move as either irrelevant to their lives, or too expensive (the 1990 reunification of Germany ended up costing more than $1 trillion).

Park Geun-hye.

If there is a bright star among the three nations of Northeast Asia, it is South Korea. Unlike Japan and North Korea, it is not suffering from economic or social stagnation. While the goals of the "747 Plan" mentioned above haven't been met yet, South Korea is doing very well nonetheless; currently it is the 7th largest trading partner of the United States, it has Asia's 4th largest economy, and it has the world's 13th largest economy. In the past, the Koreans have had the bad luck of being sandwiched between two larger neighbors, China and Japan; perhaps the twenty-first century will be the time when at least half of the peninsula can be free and prosperous, rather than a satellite of another nation. One thing's for sure--the people and government of Seoul will make sure Korea is a major player on the world scene!

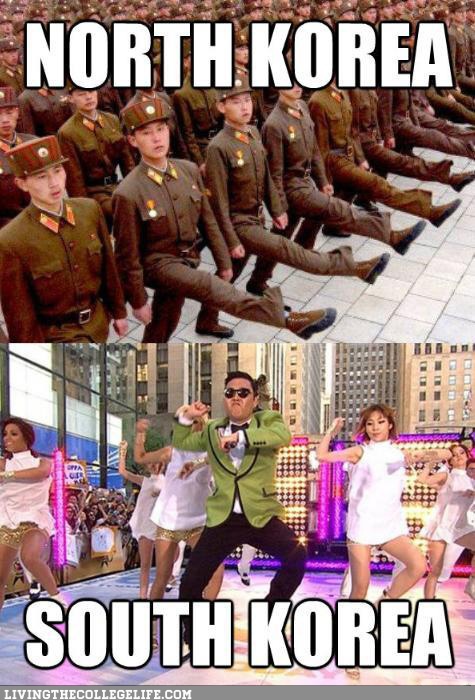

I will end the South Korea narrative with a funny picture, showing dance steps from the two Koreas. The 2012 hit "Gangnam Style" was widely popular abroad, and the first Korean-language song played on the radio in the author's off-the-beaten-path neighborhood.

The Bizarre Land of North Korea

Even at their worst, South Korea's leaders seemed Jeffersonian compared to the northern strongman, Kim Il Sung, who made North Korea the most oppressive state in Asia, perhaps in the whole world, during his 46-year reign. The state he built from the ruins of the Korean War is a modern-day version of the "Hermit Kingdom" (see Chapter 3); few foreigners have seen North Korea because it is hermetically sealed off from the rest of the world,(15) and contrary to the most basic teachings of communism, it has experienced three generations of hereditary rule. Describing it can be a challenge; if North Korea was written about in a work of fiction, most of the readers probably wouldn't believe such a place could be real.

The Kim dynasty (so far). From left to right:

Kim Il Sung, Kim Jong Il, Kim Jong Un.

Most buildings in North Korea date to the period between 1953 and 1980, and were often built with help from the Soviet Union or Communist China. Older buildings, especially in Pyongyang, were destroyed by the battles fought during the war, and more recently the country hasn't been able to afford new ones.(16) The main architectural features are giant statues and other monuments to Kim Il Sung and his son Kim Jong Il. You cannot escape the nonstop propaganda put forth, from radio sets that cannot be turned off, to plays/concerts that call for adoration of the dictator, to vast stadium displays where thousands of people hold up cards to make instant murals. In these ways Kim Il Sung built up a cult of personality that put those of Stalin and Mao to shame(17); he went so far as to have every road in North Korea built with an extra lane, just for his private use. After his death on July 8, 1994, Kim Il Sung was declared president of North Korea forever. Consequently Kim Il Sung's signature routinely appears on government documents, as if he was still alive and running the state, and his successors can take titles like chairman of the Communist Party and commander in chief of the Korean People's Army--but they cannot call themselves president.

North Korea was not amused when the USSR launched its de-Stalinization campaign in 1956. Ten years later, Kim Il Sung denounced China's Cultural Revolution, though Chinese troops had saved North Korea during the Korean War. Because of this, and in keeping with North Korea's ideology of Juche ("self-reliance"), North Korea declared its political independence from both the Soviets and the Chinese in 1966. North Korea also stayed out of the Sino-Soviet dispute suring the 1960s and 70s for the same reason.

In 1968 tensions increased when the US spy ship Pueblo was captured; the crew was released after being held for several months, while the North Koreans kept the Pueblo and turned it into a museum. Other war-threatening incidents included the following:

- The 1976 murder by thirty axe-wielding North Koreans of two American army officers, who went into the demilitarized zone (DMZ) to trim a poplar tree that was blocking their view of the other side. The next time Americans entered the DMZ, 813 troops (South Koreans as well as Americans), backed by tanks, helicopters and B-52s carrying nukes, were sent to cut down the tree, and they called it Operation Paul Bunyan. Yes, World War III almost started over who owned a poplar tree in the middle of Korea.(18)

- A 1983 bombing in Rangoon, Burma (now called Yangon, Myanmar) that killed 14 South Koreans.

- The blowing up of a Korean Air Lines jet off the coast of Myanmar in 1987, which left 115 passengers and crew members dead.

- The kidnapping of a handful of Japanese citizens, from Japan itself, during the 1970s. The idea was that through brainwashing, those kidnapped could be turned into spies when sent back to Japan. North Korea admitted doing this in 2002, and allowed some of the victims to leave, but claimed the rest had died and sent some ashes it claimed were their cremated remains (they weren't).

- When a tunnel was discovered under the DMZ, North Korean troops claimed it was part of a coal mine, and tried to fool UN inspectors by painting the walls black!

- North Korea's nuclear program, which we will discuss below.

Talks between the two Koreas on trade links and cross-border visits (for families divided by Korea's North-South split) have been held on and off since 1972. North Korea announced in 1990 that it would seek full normalization of its relations with Japan. The following year, North Korea was granted UN membership, said that it would permit international inspection of its nuclear facilities, and signed a landmark treaty of reconciliation and non-aggression with South Korea. This led to the signing of an accord permitting trade in 1992.

By this time, North Korea was in serious financial trouble, because the Cold War had ended in the outside world, leaving North Korea as the last outpost of Stalinist-style communism and the only remaining "extreme command driven" economy. We mentioned in Chapter 4 that when the Korean peninsula was divided, the North got most of the industry. As late as the 1970s, North Korea's gross domestic product was twice as great as South Korea's, but then the North's GDP stagnated in the 80s, and shrank in the 90s, while that of the South grew by leaps and bounds; today South Korea's GDP is forty times greater. In 1989 the USSR and China, hampered by economic difficulties of their own, stopped supplying goods at "friendship prices." Then came six years of bad harvests, and a ravaging 1995 flood, followed by a long, cold, dry winter. Even then, the Pyongyang regime was not willing to compromise its ideology, or relinquish some of its power, to prevent mass starvation. In 1996 the country ran out of food; grain rations were cut back to a starvation level of 200 grams a day, and refugees started defecting to South Korea and China; among those who stayed behind, it is estimated that hundreds of thousands starved to death. The worst part of the famine ended in 1998, but today North Korea still isn't capable of feeding its population. By the end of 1993 North Korea also had a trade deficit of more than $1.7 billion. As Pyongyang's credit rating plummeted, the commerce between North Korea and China, which peaked at $226 million in 1994, shrank to just $9 million in 1996. As a Chinese official explained it: "What they want--grain--we can't give them. What they want to sell, we don't want."

Tensions rose in 1993 when the North Korean government stated that it would not allow inspectors from the United Nations International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to enter key nuclear power facilities to monitor compliance with the Nuclear Proliferation Treaty (NPT). By this time, the outside world realized that North Korea was turning its nuclear power program into a nuclear weapons program. Evidence appeared that North Korea had diverted enough plutonium from its power plants to create at least two nuclear warheads, and was testing medium-range missile systems to deliver them with. The United Nations responded with condemnation and threats of international sanctions. The crisis was defused when former US President Jimmy Carter went to Pyongyang as an unofficial emissary, and the Kim Il Sung regime announced that it would freeze the nuclear weapons program, in return for technical assistance on the nuclear power program.(20) President Clinton announced on June 22 that high-level talks would be held in July in Geneva, Switzerland, between the United States and North Korea, but they did not take place, due to Kim Il Sung's death, three weeks after the Carter visit.(21)

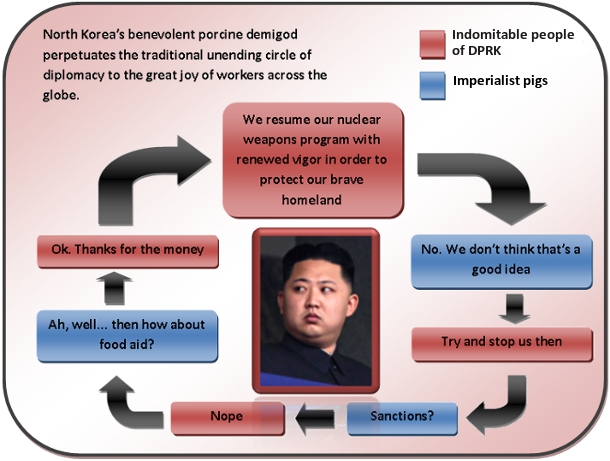

If the Cold War had still been going on, the Western response to North Korea's famine and nuclear violations would have been to let the Pyongyang regime sink, and later cheer at the news of North Korea's end. But a country that is both hungry and well-armed is a dangerous country--it was likely that the North would use its army of 1.2 million men to start a war, in order to get the food it needed. Thus, the United States, South Korea, China and Japan all responded to the threat by propping up Pyongyang with emergency aid, hoping that if the North collapsed, it would be a "soft landing" like what happened to East Germany, instead of a disastrous meltdown. Since the 1990s, North Korea has played a game of brinkmanship; to keep the food and cash coming, it periodically either does nuclear testing, or tests the rockets that would be used to deliver nuclear warheads. The most successful rocket test to date came in 1998, when a test missile flew over Japan and landed in the Pacific. Other test launches have been duds by comparison, though Pyongyang insists it could hit the US mainland with a missile in the event of war.(22)

Steps in the brinkmanship cycle, with North Korea's actions marked in red, and the outside world's responses marked in blue. This chart came from a humor website, Cracked.com, but it effectively explains a serious topic.

Unfortunately for the rest of the world, in 2002 North Korea also announced that it had not complied with any of the terms it had accepted in Jimmy Carter's 1994 agreement. Since outside inspectors had never been allowed to enter the facilities and verify that weapons development had stopped, the program simply continued the way it had before. Then in 2003 the North Korean government withdrew from the NPT, and announced that it had actually already produced a number of nuclear weapons. There have been five nuclear tests since then, conducted in 2006, 2009, 2013, and two in 2016; each has been detected as an underground explosion, with an estimated force between one and nine kilotons. It was comparatively easy for North Korea to bargain away its right to build nuclear weapons when it did not have any, but now that it is a bonafide nuclear power, the chances of it giving up those weapons is far less likely; the real strength and number of the warheads it has is still unknown, though. Following a series of six-party talks (involving North & South Korea, the United States, China, Russia and Japan), North Korea agreed in 2007 to shut down its main nuclear facility, the Yongbyon reactor, in exchange for fuel aid and normalization talks with the United States and Japan. While the reactor in question was turned off, the agreement fell apart after another North Korean missile test.in 2009 (and the reactor was restarted in 2013).

Even if North Korea did not have nukes, it would be a problem for the present-day United States. To make some money, North Korea has sold its missiles and missile technology to nations that probably should not have them, especially Iran. North Korea has also resorted to selling narcotic drugs like meth, and is the world's largest counterfeiter of American hundred-dollar bills. People in the DMZ run the risk of being grabbed and taken to the North Korean side of the border, and tourists who foolishly visit North Korea are regularly arrested on trivial charges. In both cases the victims are sentenced to several years of hard labor, which usually lasts until a foreign celebrity comes to bail them out (see footnote #19).

We mentioned in the previous section that North-South relations were at their best in 2000, when southern president Kim Dae Jung met with Kim Jong Il. One of the agreements reached during the Kim Dae Jung presidency was the first major inter-Korean cooperation project. Mount Kumgang, a mountain on North Korea's east coast, had been a scenic attraction since ancient times, and North Korea realized it could earn tourist money from South Korean tourists visiting the mountain. In 1998, South Koreans were allowed to travel to Mount Kumgang, first by cruise ship, and later by busses crossing the DMZ. By 2002, more than a hundred thousand South Koreans were coming every year, the land around the mountain was turned into a national park, the Mount Kumgang Tourist Region, and hotels had been built for the benefit of the tourists. All was going well until 2008, when North Korean soldiers shot dead a South Korean woman on a beach who had wandered into a restricted zone. South Korea stopped conducting tourists to Mount Kumgang, and only a handful of visitors have come since then, most of them Chinese and Westerners.

So far the most successful North-South cooperation has been at the Kaesong industrial park, created in 2003. Kaesong was the Korean capital under the Wang dynasty (see Chapter 2); now it is a city just north of the DMZ. Here South Korea has built and run factories which employ North Korean workers, to produce goods for consumption in the South. From this arrangement the South gets cheap labor, which is no longer available south of the DMZ, while the North gets jobs and an income as large as $90 million a year. Northern workers also get one square meal each day, which matters as long as the country is going hungry, topped off with a cookie-and-marshmallow sandwich dessert called a "Choco Pie" (those are "Moon Pies," for readers in the southern United States). Rising tensions between the North and South led to shutdowns of the Kaesong factories in 2013 and 2016, so obviously the road to peace is a bumpy one.(23)

After the turn of the century, Kim Jong Il's health began to deteriorate, so he decided to name a successor.(24) His eldest son, Kim Jong-Nam, disqualified himself, when he tried to visit Tokyo Disneyland in 2001, using a fake passport. After all, when you're a supervillain-in-training, it's okay to be cultured, but you can't let others know that you like Mickey Mouse! Kim Jong Il banished him to China, and after that he lived a playboy lifestyle, with two wives, a mistress and three children. He traveled from country to country to keep ahead of any North Korean agents. That worked until February 2017, when two prostitutes walked up behind him in Kuala Lumpur airport and wiped a lethal nerve gas on his face. Back in Korea, the second son, Kim Jong-chol, was accused of "unmanliness," so the third and youngest son, Kim Jong Un, was formally installed as heir in 2010. On December 17, 2011, while traveling on a train outside of Pyongyang, Kim Jong Il died suddenly; he is thought to have suffered from a heart attack, but the government never stated what the cause of death was.

Like his father, Kim Jong Il was given new titles posthumously, with the idea that he would hold them for eternity. 28-year-old Kim Jong Un took charge, as the world's youngest head of state. North Koreans noted that he resembled Kim Il Sung at the beginning of his career, while the non-communist world thought he looked like a fat boy half his age. For his education, he received a physics degree at "Kim II Sung University," and an "army officer degree" at "Kim II Sung Military University" (where else?). So far Kim Jong Un has mainly acted like a brute; the country is still dotted with Gulag-style prison camps, with much of the population locked up, tortured, and/or starving. At the end of 2012 he began to purge his father's close associates, replacing them with officials loyal only to him. In the most notorious example, he executed his uncle, Jang Sung-taek, after accusing him of contacting his disgraced brother, Kim Jong-nam. In March 2014 he ran in an election for the Supreme People's Assembly, and the government reported that the voters chose him unanimously.(25)

In May 2016, Kim Jong Un convened a Communist Party Congress, the first held since 1980, to increase his hold on power, and the Congress unanimously elected him party chairman.

One difference between Korea and the formerly divided Germany is that before the Berlin Wall came down, East Germans knew what life in the West was like, from Western television and radio. This has not been the case in North Korea, where the only legal TV sets and radios are pre-set to state channels. Lack of knowledge about the outside world undoubtedly kept North Koreans from rising up against their oppressive government; most of the time they didn't really know how poor they were, either. That could change in the near future, though. Thanks to the Choco Pies, Northerners no longer believe the propaganda which claims South Koreans are starving. And a growing number of North Koreans can watch South Korean TV programs, on contraband USB sticks and DVDs smuggled from China. Finally, a steady stream of luxury goods -- like fancy cars, alchohol and cigarettes -- can still come across the border from China, even with the current international sanctions on today's Hermit Kingdom. Because compromises with capitalism have allowed China to prosper in recent years, it would be ironic if someday the North Korean regime -- one that has praised communism and denounced capitalism at every opportunity -- is brought down because it let in too much merchandise from another communist country.

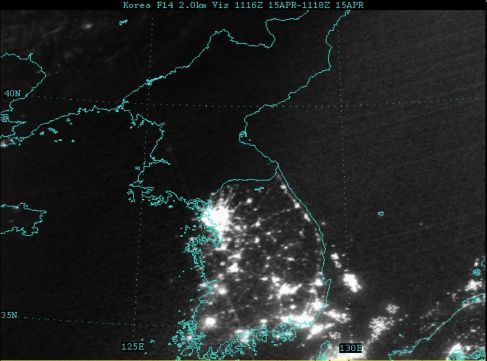

Have you heard of Earth Hour? North Korea practices it every night; then the difference between North and South Korea is visible from space. This photo, taken from a weather satellite in 2005, shows every city in South Korea lit up brightly, and you can even see the highways as lines between the cities. By contrast, except for a barely visible grey smudge marking Pyongyang, there are no lights in North Korea at all.

And for those who prefer color pictures, here are northeast China and Korea, as seen from the International Space Station.

THE END

FOOTNOTES

1. Tojo shot himself in the chest when the Allies came to get him, but the gunshot wound was not fatal, and he lived to be hanged in 1948.

2. The Japanese-Americans living on the Pacific coast of the US mainland (though not in Hawaii) were put in detention camps for the duration of the war, because they were seen as a security risk. A few did see military service, though, and they fought bravely in Europe, to the dismay of those Germans who thought all Japanese were on their side.

3. The police make up somewhat for the lack of an armed forces by being as well equipped as any army elsewhere; they have tanks, for instance.

4. The Bonin & Volcano Islands, the site of the fierce battle of Iwo Jima (see the previous chapter), were given back to Japan in 1968. Likewise, the US returned the Ryukyu Islands in 1972. There are still US servicemen stationed on Okinawa, though, and occasional abuses by them have caused the Japanese to reconsider the terms of their defense agreement with the United States.

Russia took the southern half of Sakhalin and all of the Kurile Islands as its reward for assisting the United States and Britain in the final week of the war. This included the four southernmost islands in the chain--Iturup, Kunashir, Shikotan and Habomai--which Russia had never ruled before, but had been occupied by Japan as far back as 1855. Since the 1950s Tokyo has argued that those four islands should have been returned, and arguments with Moscow over fishing rights in that area break out from time to time. This kept Japan on the side of the Americans during the Cold War era, and today relations between Japan and Russia are still cool.

5. During the first period when the Liberal Democratic Party was out of power (1993-96), there were three prime ministers. Two of them came from short-lived parties that had broken away from the LDP, and the third was from the leftist Social Democratic Party. The second period (2009-2012) saw three prime ministers from the centrist Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ).

6. A 1972 cartoon showed a Japanese corporation's board meeting, where the president announces, "In the next war we won't attack Pearl Harbor, we'll buy it!"

7. Japan also came under accusations from environmentalists, who declared the Japanese were overfishing the oceans and depleting the populations of endangered species, especially whales and dolphins. In the 1980s Japan agreed to stop commercial whaling, a tough decision for them to make in view of their fondness for any kind of seafood. They still kill a few hundred whales annually for "scientific" purposes, but will not give details on what kind of research is being conducted.

8. The concentration of people in Seoul made it easy to give them all DSL connections when the Internet became available. When it comes to broadband Internet service, South Korea is the most wired country in the Far East.

And here is Korea.net, the South Korean government website.

9. For those keeping track, the Third (1963-72) and Fourth (1972-79) Republics existed while Park Chung Hee was president. The next president/dictator, Chun Doo Hwan, presided over the Fifth Republic.

10. One of the most successful entrepreneurs in the 1990s was Katsuhei Kojima, the owner of a chain of department stores that bear his name. In 1995, while most economists said that finicky Japanese consumers would not buy foreign-made products, Kojima made a killing by importing 10,000 American refrigerators, which are easier to use--and cost only a third as much as Japanese models.

11. The Chinese are now rapidly catching up on the United States, as if they are hell-bent on regaining the first-rate status their country enjoyed before the nineteenth century (see Chapter 5 of my Chinese history series). So if you don't read this footnote immediately after I write it, don't be surprised to find that the Chinese economy has become the new Number One.

12. A 1999 government estimate reported that 6,500 religious cults operate in Japan. One of the richest was Honohana, which reportedly had assets worth $600 million; its founder was charged with bilking followers of up to $100,000 to alter the negative fates he detected by examining their feet. The founder of another cult named Life Space died in August 1999, but four months later police found his body in a Tokyo airport hotel room, where his followers treated him as if he was still alive (The faithful insisted that the dried corpse was responding nicely and had recently enjoyed some tea.). The most notorious cult, a doomsday group called Aum Shinri Kyo (Absolute Truth), launched a nerve gas attack in the Tokyo subways that killed 12 and injured more than 5,000 (March 1995).

13. One of the high points of Kim Young Sam's presidency came on August 15, 1995, which marked the 50th anniversary of both the end of World War II and of Korea's liberation from Japanese rule. On that day the South Koreans began the demolition of the Japanese General Government Building in Seoul, which was the seat of the Japanese governor of Korea, and had been built next to the old Gyeongbokgung palace complex, to remind the Koreans who was boss.

14. In 2004, an announcement was made that between 2007 and 2012, the capital would be moved from Seoul to Gongju, a city 75 miles to the south. Gongju had been a capital once before; from 475 to 538, when it was named Ungjin, it served as capital of the kingdom of Baekje (see Chapter 1). The reason given for the move was to ease congestion in Seoul; it would also make the government more secure, because Seoul is close enough to the demilitarized zone to be within range of North Korean artillery. However, polls showed a slight majority of South Koreans were against the idea. And the experience of other countries that have moved their capitals (Belize, Nigeria, Tanzania, Ivory Coast, Myanmar) shows that when the old capital city is downgraded to just a commercial center, it still remains almost as crowded as before. Finally, the Constitutional Court squashed the plan by ruling that the move would be unconstitutional, if done without a national referendum approving it, or an amendment to the constitution. Now it looks like if the move ever happens, only some government agencies will go to Gongju, allowing Seoul to remain the official capital; then South Korea will have two capitals, like Bolivia.

15. According to the latest report I saw, only 605 North Koreans--less than one in 40,000--are permitted to access the Internet. The country's official website is poorly designed (take it from someone who built his own websites from scratch), is written in English only, has only been updated slightly since the 1990s--and runs on an American server. Compare this to what I said about South Korea's Internet service, in footnote #8 above.

17. North Koreans came to call Kim Il Sung "Great Leader," and Kim Jong Il "Dear Leader." Kim Jong Un has been called the "Great Successor," but he doesn't promote the title the way his father and grandfather promoted theirs. As much as 30 percent of the lessons in North Korean schools have to do with the lives of their leaders, and the official propaganda routinely makes absurd claims about them. For example, the North Korean news reported that Kim Jong Il invented the hamburger, and when he played his first game of golf, he shot 38 under par, and scored eleven holes-in-one--whereupon he decided that was good enough, and never played again.

18. Afterwards, the North Korean DMZ guards enshrined the axe used to kill the Americans.

The cease-fire agreement ending the Korean War allowed three villages to stand in the DMZ. We saw one of them already, Panmunjom, which is where North and South Korean leaders go when they have to meet in person. At the Panmunjom border crossing, a constant staredown between American, South Korean and North Korean guards has been going on since 1953. After more than twenty years of being underfed, today's North Koreans are visibly shorter than South Koreans. South Korea takes advantage of this height discrepancy by requiring that its guards at Panmunjom be at least five-foot-eight and have a black belt in karate; likewise, the Americans try to intimidate the other side by selecting their biggest soldiers for this assignment. North Korea in turn employs officers who aren't as malnourished as the rest of their country, and they will usually have more guards on their side, using numbers to offset their smaller stature, and to keep an eye on any in their unit who might try to run through the gate to the South.

The other two villages are next to each other, South Korea's Daeseong-dong and North Korea's Kijong-dong. Life is unusual enough for the 200+ farmers in Daeseong-dong, who live here because their ancestors lived here, too. When the farmers work in their rice fields, armed South Korean soldiers stand nearby to guard them, because the border is no more than 100 yards away. The authorities in Seoul give the farmers special benefits, exempting them from doing military service and paying taxes. However, they are also under a curfew; they have to be home by sundown and they have to bolt their doors and windows by 11 PM, to keep out any North Koreans who might sneak across the border to kidnap them. In addition, the farmers are not allowed to move away.

By contrast, Kijong-dong is a modern-day "Potemkin village," where North Korea maintains a fancy facade, but nobody lives there. The name of the place means "Peace Village," but "Propaganda Village" is a more accurate description. While most of the buildings are painted white with blue roofs to make them attractive from a distance, on the inside they are as hollow as the Ryugyong Hotel, lacking interior walls, floors, and glass for the windows. To complete the illusion, electric lights operate on timers (the typical North Korean farming village doesn't have electric lights), and maintenance workers are brought in each day to sweep the streets and pretend they are residents going about everyday business. When South Korea put up a 323-foot-high flagpole in Daeseong-dong, the North Koreans outdid that by erecting a 525-foot-high tower in Kijong-dong to serve as their flagpole. Finally, loudspeakers in the village blare North Korean propaganda messages and music, in an effort to convince South Koreans within earshot that the land on the north side of the border is a worker's paradise. So far there is no record of anyone defecting because they were fooled by this ghost town.

19. At the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, the star North Korean gymnast agreed to appear in a selfie with her South Korean counterpart, leading to hope that someday the two Koreas can reunite.

20. Carter went without the permission of the current president, Bill Clinton. Clinton had to accept the agreement he brought back because the United States has never had diplomatic relations with North Korea, and thus there was no ambassador or official negotiator to go there. North Korea's subsequent refusal to honor the agreement showed that Carter could still make trouble, long after his presidency ended. Another self-proclaimed ambassador to North Korea is basketball star Dennis Rodman, whose behavior is almost as creepy as that of his hosts in Pyongyang.

21. Despite the best efforts of communism, some aspects of human nature, like superstition, do not change. According to North Korean radio, a violent storm erupted on Mt. Paekdu, the supposed birthplace of Korean communism, at the very moment Kim Il Sung's heart stopped beating, and lasted for three days. This is the same spot where Korean myth taught that Hwanung, the ancestral god of the Koreans (see Chapter 1), first came to earth. Likewise Kim Jong Il revived a very ancient Far Eastern custom, by allowing three official years of mourning, before accepting his role as the new head of state in 1997. There certainly was a lot of mourning, because aside from the Japanese, Kim Il Sung was the only leader the North Korean people had known. After Kim Jong Il's death, Kim Jong Un continued this custom, disbanding a so-called "pleasure squad" of women who entertained his father, and recruiting a new squad in 2015, after the mourning period ended.

Recently the North Korean calendar was reorganized to count years from 1912, the year of Kim Il Sung's birth. So the year when I wrote this was 2015 in Western nations, but in Pyongyang it was 104.

When Japan annexed Korea in 1910, it put the whole Korean peninsula in the same time zone that Japan is in (UTC+9). That was the way things stood until August 2015, when North Korea celebrated the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II by turning its clocks back thirty minutes. As North Korean state-run TV put it, the new time zone "shall be fixed as the standard time of the DPRK [Democratic People’s Republic of Korea] and called Pyongyang time. The wicked Japanese imperialists committed such unpardonable crimes as depriving Korea of even its standard time." They probably got the idea from South Korea, of all places. From 1954 to 1961, South Korea had its clocks set thirty minutes behind those of Japan, but then Seoul decided that UTC+8.5 caused too many inconveniences, and returned to UTC+9. Since then there have been proposals to set South Korean time back thirty minutes again, for the same purpose that Pyongyang declared, to get rid of one of the ways in which Japan changed Korean culture. But knowing how the two Koreas are rivals, you can be sure that if South Korea moves its clocks back, North Korea will reset its clocks again, to avoid being in the same time zone as the South.

22. Click here to see an animated picture of a North Korean rocket launch that the author found (1.44 MB, will open in a separate window).

23. Choco Pies are so popular among North Koreans that they began using the treats as a substitute currency; on the black market they can be worth as much as $5.14, compared with 24˘ on the open market in South Korea. When the closing of the Kaesong factories caused North Koreans to suffer from chocolate withdrawal, South Koreans came to the rescue by loading fifty balloons with Choco Pies and cookies, and floating them across the DMZ. Pyongyang was furious, and threatened to shell the spot where the balloons were launched. In the end, the regime undercut the black market by producing its own Choco Pies (an inferior version of the originals, of course), and outlawing the South Korean ones. And yes, judging from recent photos of Kim Jong Un, it looks like he got rid of the contraband treats by eating them.

24. By this time, the media had taken an interest in whatever idiosyncrasies it could discover about North Korean leaders. For example, Kim Jong Il was rumored to spend $350,000 a year on brandy, and one witness claimed he was a huge fan of Western movies, especially James Bond thrillers.

Speaking of movies, the most popular American in North Korea is a movie star you probably never heard of. Since the Korean War ended, six American soldiers are known to have defected to North Korea. Only one of the defectors, Charles Jenkins, was ever allowed to leave again, probably because he married a Japanese abductee that he met soon after his defection. One of those who stayed was Private James Joseph "Joe" Dresnok (1941-2016). In 1962 his wife divorced him, and he was about to be court-martialed for leaving his base without permission for a night of chasing women, so one day he ran across the DMZ. Knowing that North Korea was a Stalinist, war-ravaged hell-hole, he might have trying to commit suicide by stepping on a landmine, but instead he survived his run, was captured by the guards on the other side, and sent on a train to Pyongyang for interrogation. That was last anyone in the outside world heard from him until 2006, when the Pyongyang regime let two British filmmakers, Dan Gordon and Nick Bonner, have a meeting with Joe Dresnok, and they exclaimed, "It would have been less surprising to meet Elvis Presley." North Korea had put Joe Dresnok to work by casting him as the American villain in their movies, and since North Korean movies are all propaganda films, nobody abroad watched them, but to North Koreans Dresnok became the local equivalent of Christopher Lee. In addition, he married a Romanian, probably the only Caucasian woman in North Korea, and their two sons also got to play token white bad guys in those movies. I guess this is the only possible happy ending on the north side of the DMZ!

25. 2014 ended with hackers breaking into the computer network of Sony Pictures and leaking details on the company and its movies, especially The Interview, a comedy about a plot to assassinate Kim Jong Un. North Korea denied having any part in the hacking; this was more likely an inside job, done by one or more disgruntled employees. Still, Pyongyang warned previously that The Interview had better not be released, and approved of what the hackers did. Ten years earlier, another political comedy, Team America: World Police, portrayed Kim Jong Il as an evil marionette (see below), but that time all North Korea did was request that other countries not show the film.

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A Concise History of Korea and Japan

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|