| The Xenophile Historian |

A History of Christianity

Chapter 1: THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE EARLY CHURCH

1 to 300 A.D.

This chapter covers the following topics:

Introduction

Good morning. This is the text from eight classes I taught for the Bethel Bible Institute (in Orlando, FL) on the history of the Christian Church. The first four classes, which looked at Christianity up to the start of the Protestant Reformation were taught in the summer of 1996. The rest of Church history, from 1500 to the present, was covered in early 1997.

The most obvious thing we will be tracking is nearly two thousand years of tremendous growth. According to 1994 population figures there are now 1.87 billion people who profess some form of Christianity, or more than one out of every three in the world. And this started from a most humble beginning. The founder of Christianity was not a prince or a priest as the world defined it, but a commoner who owned nothing except the homespun robe that he wore. His twelve closest followers were a mostly uneducated bunch, which included such characters as a zealot (first-century terrorist) and a tax collector; Judas Iscariot was probably the only respectable member of the bunch! (Read the story about the first century consulting firm for details!)

The growth of the Church from this unlikely start to a world-encompassing faith is one of the more positive trends of history. True, there have been some bad episodes, like the persecutions that were carried out "in the name of Christ," but God has also regularly raised up new men and women to bring the Church back into line with what it should believe and how it should live. Some believe in an evolutionary process, where the Church is gradually getting better all the time; others believe that imperfect man will always mess up God's perfect message, but at the second coming God will set everything right again. Whichever theory you subscribe to, I think you will find much that is encouraging in what we will cover in the next lessons.

How God Prepared the Way

Before the Lord could make His appearance on earth, civilization had to be prepared so that there would be widespread communication and acceptance of what He taught. John the Baptist is identified in the New Testament as a person set aside for this purpose, but there were also many not-so-obvious trends worthy of note:

1. The Romans lost faith in the gods of their ancestors. The myths surrounding Jupiter, Mars, Minerva, etc. were now viewed as rather silly stories about oversized people acting like oversized people (this attitude probably came from the Greek philosophers; Socrates said, "Of the gods we know nothing"). In addition, the Roman religion had long ago passed from simple ceremonies to elaborate public rituals which had little meaning for the layman. The old gods were kept around because they symbolized the state, but the Romans had always been a superstitious, rather than a religious people; they were more interested in omens and soothsayers than in whether or not they were keeping commandments. By the time the Roman Republic became the Roman Empire, some of its citizens had begun looking for a superior kind of spiritual sustenance, one which their gods could not supply.

2. Roman law and citizenship created more than two hundred years of peace, and (from Western man's point of view) a one-world government. The empire also built roads and encouraged commercial traffic, which greatly helped the spread of the Gospel. I believe it was part of God's plan that the Empire did not fall until churches had been established in every province of it for at least a hundred years.

3. Two languages, Latin and Greek, were understood just about everywhere. Jesus and the Apostles probably used Aramaic in everyday life, but because Greek was so widely used it would become the language for preaching and for the writing of the New Testament.

4. The impact of Judaism. Greeks first became acquainted with the Jews in the fifth century B.C., and the Romans did in the second century B.C. Jews gave their Gentile rulers the Old Testament, the idea of taking off one day a week for rest, the concept of Monotheism, and hope for a Messiah (Gal. 4:4). In return the Jews were not required to worship the emperor as a god, the way Rome's other subjects did, though they did gratefully offer prayers and sacrifices for his well-being. Most emperors could accept this, since they believed they became gods after they died, but less prudent emperors like Caligula and Nero insisted on being worshiped in their lifetime, and viewed those who did not do so as disloyal; this sparked some of the Jewish revolts, particularly the Bar Kochba rebellion (132-135).

Estimates of the numbers of Jews living around 1 A.D. range from several hundred thousand to as many as five million. Whatever the figure was, more than half of them lived in Iraq, which was part of the Parthian (and later Persian) Empire. In the West, they appear to have made up around one tenth of the Roman Empire's population. It takes more than just large families to explain how the Jewish community reached this size, and it probably came about through a number of converts (proselytes) from the surrounding Gentile population. Exact details are not available, though.

Jesus of Nazareth

The only detailed account of how Christianity got started is in the first five books of the New Testament. Since it is expected that most of the readers of this work will come from a Christian background, or be at least familiar with the story of Jesus, most of what is in the Gospels will not be repeated here, except to explain the effects on Middle Eastern history in general; it is also safe to say that nobody can improve on the original story given to us by Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.

At first Christianity was basically a reaffirmation of the Middle Eastern view concerning the nature of the world and man. The teachings Jesus gave on salvation and the coming of the kingdom of God were an elaboration on what the Jewish prophets had taught centuries earlier. The new faith at the same time generated an idea that was enormously appealing--that God Himself had come to earth and wanted to have a personal relationship with His people.

The twelve Apostles of Jesus expected Him to fulfill all of the Old Testament prophecies at once, judge the world, right all wrongs, and establish Israel as an everlasting kingdom. When instead the Romans arrested and crucified Jesus on a trumped-up charge of sedition (29 A.D.), it looked like everything he did was for nothing. But soon afterwards the dispirited Apostles gathered in an upstairs room and suddenly felt again the heartwarming presence of their Master. Now they were convinced that the death of Jesus on the cross was not an end but rather a beginning. If they doubted it before, now they knew for certain that Jesus was the Messiah prophesied in the Old Testament, and that He would save whoever accepted Him as Lord before He returned in glory on the long-awaited day of judgment. During the next seven weeks five hundred of His followers saw their resurrected teacher before he left them for the last time, giving them a final command to spread the Gospel to "Judaea and Samaria, and to the uttermost part of the earth."

The good news could not be kept a secret. On the contrary, the Apostles bubbled over with excitement and told anyone who would listen what had happened and was going to happen. Peter, for example, who had denied his master when the Romans arrested Jesus, now proclaimed Him with the courage of a lion. Initially these early Christians stayed in and around Jerusalem, but when Stephen was stoned, and Herod Agrippa I and various Jewish leaders tried to stamp out the new movement, they moved their headquarters to Antioch in Syria, and the number of people who heard the Gospel grew exponentially.

The Rabbi from Tarsus

At this point the early Church made a convert who would become the greatest missionary of all. This was Saul of Tarsus, a Pharisee who had distinguished himself by his outstanding adherence to the Law and his persecution of the first Christians. Saul chased them from Jerusalem but was converted through a vision of the risen Christ on his way to Damascus. Temporarily blinded, he found his way to a Christian named Ananias, and when cured he began to preach the Gospel vigorously. Before long his former friends made plots against his life, and Saul had to escape Damascus by being lowered over the city wall in a basket. Saul wandered in Arabia for a while and then returned to Jerusalem, but here he faced a double problem: Christians who feared his conversion was not really genuine, and Jewish leaders who now viewed him as a traitor. He went home to Tarsus and lay low for about a decade, until the Church of Antioch called him back into the ministry. From this point on Saul is called by the Greek version of his name, Paul.

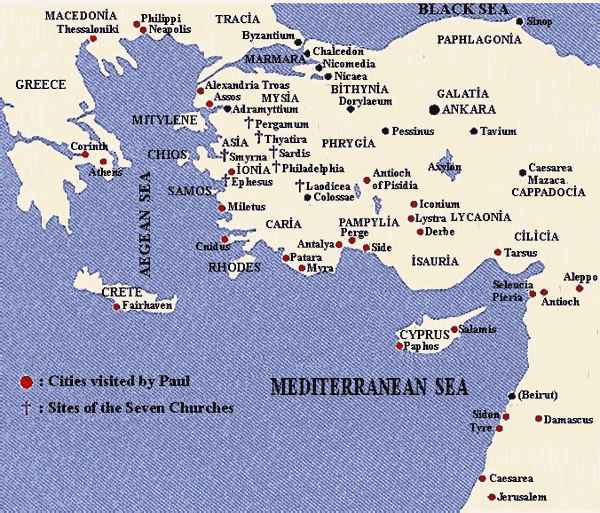

Using Antioch as his starting base, Paul now went on three epic missionary journeys through Asia Minor and Greece, which are described in detail in the second half of the Book of Acts. Wherever he went, he first located the nearest synagogue to preach in, and when the Jewish congregation would not have him, he took his message to the Gentiles outside. Previously the Apostles had converted a handful of non-Jews (e.g., Philip and the Ethiopian eunuch, Peter and the Roman centurion Cornelius), but Paul was more dedicated to this ministry than anyone else; he even brought Peter back into line when Peter slipped into his old habits and associated only with Jewish Christians (Galatians 2:11-16). It was Paul who offered the Gentiles salvation without the necessity of following the 613 commandments of the Torah (plus all the rules the Pharisees & Sadducees had tacked on more recently). Being fluent in Greek, he was also able to express the message of Jesus in terms his Greek listeners could understand. In the long run, Paul's activities caused a total change in Church demographics--by the end of the first century most of its members were non-Jewish, and would remain that way to this day.

The area where Paul was active on his three missionary journeys. When he introduced Christianity to the Greeks, they became Zeusless!

Paul had special freedom of movement because he was born a Roman citizen; that opened doors for him that were closed to other Jews. He concluded his third journey in Jerusalem, bringing money he had collected for the poor Christians of the mother church. When he arrived he was seized by a Jewish mob and would have been lynched, had not the Romans arrived in the nick of time. Paul had to stand trial to refute the charges against him, but rather than face a biased court in Jerusalem, he appealed to the Roman Emperor Nero for justice. He was sent to Rome as a prisoner, surviving a shipwreck at Malta on the way. After spending two years in Rome (the Book of Acts ends at this point), Paul was probably released to conduct some more missionary work; Romans 15 mentions trips to Spain and Illyricum (Albania) that he planned and possibly carried out (a second century believer, Clement, wrote that he did go to Spain). Finally around 64 A.D. he returned to Rome and became a martyr in Nero's first persecution of the Christians. Because of his Roman citizenship, he got one last privilege; he died from beheading, rather than on the cross.

The Journeys of the Apostles

Paul was not the only Church leader to travel far and wide, but his travels are by far the best documented. Each of the twelve Apostles made journeys, motivated by Paul's success as well as by the "great commission."

Unfortunately no one wrote as comprehensive a record on the journeys of the Twelve as Luke did for Paul. To fill in the many existing gaps, we have to rely on Church traditions/legends. Of course these are not the most reliable source of historical data, but where two or more separate accounts tell us the same thing (e.g., Peter died in Rome, Thomas went to India) we can guess that we are on safe ground. Also, remember that each Apostle had to go somewhere, so if only one country claims an Apostle as its missionary, he probably did go there. It is beyond the scope of this work to go into detail on their adventures. For those who want to read that, I recommend The Search for The Twelve Apostles, by William Steuart McBirnie, Ph.D. (Tyndale House Publishers, 1973). That book devotes a chapter to the traditions and hard evidence available concerning each Apostle, as well as covering the later careers of other New Testament worthies, like John Mark and Lazarus. I have also written a more detailed summary of the Apostolic adventures in Chapter 7 of my Near Eastern history papers. In the meantime, here is a quick list of where it appears that each of the Twelve went.

Simon Peter: Babylon, then Rome, where he was crucified upside down.

Andrew: Armenia, Colchis (Georgia), Scythia (the Ukraine), and Greece.

James the Son of Zebedee: Killed by Herod Agrippa I in Jerusalem (Acts 12:1-2), but some believe he visited Spain. Whether or not he went to Spain, most of his bones did; the shrine built over them, Santiago de Compostela, received more pilgrims during the Middle Ages than any other holy place west of Rome.

John: The "disciple whom Jesus loved" was the only one of the Twelve who died peacefully. He turns up in Ephesus, leading the church Paul started there, both before and after his exile on Patmos (about 96 A.D.).

Philip: Central Asia Minor (Galatia and Phrygia); some also link him with Scythia, and Gaul (France).

Bartholomew: Bartholomew teamed up with Philip at first, and the two went to Hierapolis in Phrygia and Azerbaijan. Other traditions have him preaching in India, an Arabian oasis, Iran, and Armenia, but these are unreliable.

Thomas: Babylon, Iran, and India.

Matthew: Egypt and Ethiopia.

James the son of Alphaeus: Syria, tradition makes him the first leader of the Church in Antioch.

Thaddaeus: Armenia, Iraq, and Azerbaijan.

Simon the Zealot: Egypt, North Africa, and Britain. Then he returned to Israel and journeyed through Syria, Armenia, and Iraq, before being martyred in northern Iran with Thaddaeus.

Matthias: Same as Andrew (they traveled together), but was martyred in Jerusalem, rather than Greece.

The Church Loses its Hebraic Roots

Because many Jews never accepted the idea of being ruled by pagan foreigners, trouble turned into unrest, and Judaea acquired a reputation as an unruly province. In 66 A.D. a Sadducee refused to offer a sacrifice to the health of Emperor Nero. For the Zealots this was the signal to launch the revolt they had been planning for a long time, which exploded into the Jewish-Roman War (66-73). The Romans had a justly earned reputation for cruelty, but when the alternatives are considered, Roman rule appears to have been the best realistic possibility. Radical Jews never understood this, and the result was the tragedy Jesus had predicted in Matthew 24, Mark 13, and Luke 21.

The initial battles went well for the Zealots, who fought with the ferocity of the Maccabees against a larger and better equipped foe. In a surprise attack they quickly overpowered the Jerusalem garrison, gaining control of the holy city. However, it was no longer possible to use the hit-and-run tactics that had worked for Judas Maccabeus; the Romans had seen to that by building plenty of roads, allowing them to rapidly move reinforcements anywhere. Because of that the leaders of the rebellion captured fortresses in remote areas like Masada, concentrated their troops there, and prepared for the sieges that the Romans would inevitably attempt. The war went on for as long as it did because Nero died in the middle of it and the general in charge of the war, Vespasian, made his own bid for the throne. Once he had it, he sent his son Titus with reinforcements and the long job of grinding down the opposition began. Jerusalem, along with the second Temple, was captured and destroyed in 70; resistance ended with the capture of Masada in 73.

The Romans thought they had destroyed Judaism along with the Temple in 70 A.D., since, as they viewed it, "with the removal of its source (the Temple) the trunk (the Jews) will speedily wither." The Jews were grief-stricken by the loss of their temple and their state, but they did not accept defeat. New revolts flared up in Cyrenaica (eastern Libya), Cyprus, Egypt, Asia Minor, Judaea, and Iraq in 116; they were an embarrassment to the Romans, but by 117 they had crushed them all. The next emperor, Hadrian, announced he would build a temple to Jupiter on the site of the former Jewish Temple. Coupled with this affront were prohibitions on circumcision, observing the Sabbath, and public instruction in the Torah. Nothing was more likely to goad the Jews into rebellion.

The leader of the revolt, Simeon bar Kosiba, was hailed as the Messiah by the greatest rabbi of the time, Akiba ben Joseph. Simeon was called "Bar Kochba" ("Son of a Star") by his admirers, and "Bar Koziba" ("Son of a Liar") by detractors. According to the Talmud, he was an extremely charismatic leader, who required that his soldiers cut off one of their fingers to prove their loyalty and valor, until the sages pleaded, "How long will you continue to turn all Israel into maimed men?" For two years he planned strategies and stockpiled weapons and supplies; Akiba traveled in the Diaspora, to places as far away as Gaul and Iraq, gathering support from the Jews living there. When the rebellion began, in early 132, the Roman Tenth Legion, caught by surprise, was forced to abandon Jerusalem. Bar Kochba established a provisional government, made plans to rebuild the Temple, and in the meantime set up a temporary altar for sacrifices on the Temple site. A new calendar was proclaimed and new coins were minted, both calling 132 "Year One of the Redemption of Israel." Bar Kochba was so confident that he once prayed before a battle: "O Lord, do not help the enemy; as for us, we need no help."

Moderates and pro-Roman sympathizers argued against the war, but their voices were drowned in the patriotic roar of the people. Meanwhile, Hadrian was calling in reinforcements, and brought his best general, Sextus Julius Severus, all the way from Britain to lead them. Using the same strategy that had worked in the last war, Severus chose to surround the Jewish strongholds and starve them into submission. In early 135, he finally managed to drive the rebels from Jerusalem. Bar Kochba and his men dug in at the fortress of Betar, seven miles away, but by late summer that had also been taken. Bar Kochba was slain in the final battle, Rabbi Akiba was imprisoned and tortured to death, and the rebellion was over.

After the war Hadrian finished off Judaea once and for all. Jerusalem was utterly destroyed, to be replaced by a blatantly pagan city, Aelia Capitolina, with a temple to Jupiter where the Jewish Temple had once stood. A Gentile population was brought in to settle the city, and Jews were only allowed in once a year, to visit the last remnant of the old Temple (the Wailing Wall) and grieve for what they had lost. An estimated 500,000 Jews were killed either during the rebellion or in its aftermath, and thousands more were enslaved. Even the name of the Holy Land was changed, to Syria Palestina (Philistine Syria), a name that dredged up memories of Israel's ancient archenemy. That, by the way, is where we get the modern term Palestine; it was an act of anti-Semitism on the part of the Romans.

The Bar Kochba revolt also brought an end, for all practical purposes, to Jewish Christianity. Jewish Christians did not take part in the rebellions because they had their own Messiah, not a self-proclaimed one; thus Bar Kochba and the Zealots distrusted them. After the Jewish-Roman War, the Jerusalem Christians moved to the little town of Pella, east of the Jordan. Now that they could no longer even visit the Holy City, they voted to become Gentiles so they could return to what was now Aelia Capitolina. A minority faction, however, refused to forsake their heritage, and they received the title of Ebionites, a derogatory term meaning paupers. Mainstream Christians later denounced the Ebionites as heretics, because they viewed Jesus as a man filled with God's spirit at his baptism, rather than as the son of God. The Ebionites straddled the fence until the fourth century, when the polarization between Judaism and Christianity caused them to melt away either into churches or synagogues.

The Glory Goes Away

It is difficult to trace the history of the Church in the late first, second and third centuries. Detailed records are lacking, and what we have may be myth and hearsay, rather than true history. There are several reasons for this:

1. The early Christians, with the exception of Luke, the author of Acts, did not see a need to write a history of the Church. Most of them expected Jesus to come back within their own lifetimes, and they did not think that they were creating an institution that would last for ages on this world. After Luke the first Christian to write a comprehensive history was Eusebius, the court historian of Constantine; he lived in the early fourth century, long after most of the exciting events he wrote about had happened.

2. Secular historians did not see Christianity as important--at first. Because Christianity's members came mostly from the poor/lower class elements of society, those with power and wealth ignored it for a long time. Another factor worth noting is that at least half of the early Christians were women, whose status in Greco-Roman society was extremely low. Only two non-Christian historians from the first century even bothered mentioning the name of Jesus: Josephus and Tacitus.

3. It now appears that for two and a half centuries the early Christians made up an insignificant portion of the Roman Empire's population. In a 1996 book, The Rise of Christianity, sociologist Rodney Stark argues that a growth rate of 40% per decade is enough to explain how the Church became dominant in the fourth century. According to his figures, starting with the 120 believers who waited for the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, and allowing for a growth rate similar to that of the Mormons (the Latter-Day-Saints have increased at 43% per decade in the twentieth century), there probably would have still been less than 10,000 believers by 100 A.D., in an empire he figures as having a population around 60 million. By 250 A.D. the Christian population would only be 2% of the imperial population as a whole, which may explain why none of the Roman emperors before this time made a determined effort to eradicate Christianity completely. According to this theory, the size of the Church would have reached a critical mass--about 10% of the population--around 300 A.D., and not until the 340s would Christians become the majority, a decade after Constantine. If archeologists claim that they have found no Christian-made artifacts that can be dated before 180 A.D. (aside from the books of the New Testament), it may mean that there just weren't enough Christians around to leave any evidence behind.

4. The lack of agreement on which writings were authentic scriptures. We'll cover how the Christians dealt with that shortly.

Overall one gets the impression that the glory of God left the Church in the second century, now that the Apostles were no longer around. We don't hear as much about miracles, and important decisions were made by meetings between the Church leaders, rather than waiting on the Lord for an answer. As the Apostle John had warned in Revelation 2, the Church was leaving its first love.

There was another change in the Church, because of the missionary work. Jesus had called himself "the Good Shepherd," and used parables about farming or fishing to describe the kingdom of God, but before long Christianity became an urban religion, because the Apostles always founded new churches in the cities, expecting them to convert the people in the surrounding countryside later on. When it came to getting lots of new believers quickly, however, this was the right strategy.

As church membership grew, it became necessary to set up an organization above the individual congregations, to lead the Church and keep it united against persecutions and heresies. Sometimes several churches would get together and pick one of their members to be a bishop over them all. Or a church might establish a new congregation in a nearby town, and put its original leader in charge of both the old and the new church. Organization tended to follow the Roman pattern, with all the churches in a province uniting under one bishop, so that in time the Church became an empire within the empire. The bishops traced their authority directly to the Apostles; for example, Irenaeus, the Bishop of Lyons in the late second century, claimed to be a convert of Polycarp, who in turn was converted by the Apostle John. By 250 the Church organization was nearly complete, with the bishops in the Empire's four largest cities (Rome, Alexandria, Antioch and Carthage) called patriarchs and regarded as having more authority than the rest. About the same time Cyprian introduced the Petrine Theory, which teaches that because Peter was the foremost Apostle, those who can claim to be his heirs--namely the bishops of Rome--should be leaders over the whole Church.

Byzantium (renamed Constantinople) became the new imperial capital early in the fourth century, so its bishop was elevated to patriarchal status in 381. Jerusalem joined the list in 451 because its bishop argued a good case for giving the Holy City equal representation. In the meantime, Carthage dropped to lesser status because its leaders adopted a local heresy. This brought the number of patriarchs to five, with Rome's viewed as the "first among equals."

Now that the Church's membership was predominantly Gentile, it forgot its original Jewish heritage. In its place pagan ideas crept in. Many early Christians turned to the works of Greek philosophers, using pagan intellectual exercises to strengthen their arguments; for example, the life and death of Socrates was portrayed as a pre-Christian example of how a Christian should live. This got so popular by 200 that one exasperated theologian, Tertullian, asked, "What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?" Other pagan elements may have been introduced to make conversions easier, though it is likely that not all of them were done intentionally. The current emphasis on the Virgin Mary in the Catholic & Orthodox churches appears to be a carryover from the mother goddess that exists in almost every form of paganism (Mesopotamia's Ishtar, the Egyptian Isis, the Greek Aphrodite, etc.). And the Christian holidays were placed so that they could be celebrated on or near the same days as the Roman ones. For example, the actual birthday of Jesus was unknown, so it was observed on the same day as the Mithraist birthday of the sun (December 25), and four days after the Roman holiday of Saturnalia began. In the second century there was a controversy over whether Easter should be held at the same time as the Jewish Passover; those who thought so were labeled Quartodecimans, meaning "fourteenthers" (Passover falls on the fourteenth day of the Jewish month Nisan).

At the same time, Christians felt the need for a dependable record of Jesus' life on earth. Besides the books of the New Testament we are familiar with, there were a number of other gospels, epistles, and "acts" floating around. There also was catechetical literature, which was used to instruct catechumens (new believers) in ethics, worship, and how to recognize false teaching, and some apocalyptic literature, such as The Shepherd of Hermas, which stressed repentance and holy living by vision, commandment, and parable. Many of these books were written to satisfy curiosity about things not covered in detail by the first-century authors, like the childhood of Jesus or the life of Pontius Pilate. Others were no more than imaginative romances and novels. Many popularized the ideas of fringe groups, like the Docetists, who rejected both sex and marriage. It took a long time to decide which books were authentic scripture. The Epistles of Paul were the easiest to agree on; all churches were using them by 100. The three synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke) and Acts came next, entering the New Testament before 150. John's Gospel took until 200 to be accepted because it was a favorite among Gnostics and Montanists. The last nine books had the same problem, especially Hebrews and Revelation. An Eastern Church leader, Athanasius, organized the New Testament in its present-day form in 367; the Western Church did the same at the Council of Carthage in 397.

Defending the Faith

Despite persecution by Jews, intellectuals, and the Roman state, Christianity grew steadily. In the first century the Christians had gained new followers by preaching openly, but that method was now very hazardous, and we seldom hear of it in the second & third centuries. In its place the early Christians used semi-private instruction, setting up classrooms to teach those who wished to become Christians, and baptizing them all at one time, usually Easter. Personal witnessing to friends was also popular, and probably used on most occasions. Finally they resorted to a tactic long used by the Greeks--philosophic argument. This came about because of the strange rumors that went around concerning the church. Non-Christians often accused Christians of the following:

1. Antisocial behavior, because they held their worship services in secret places like underground cemeteries (catacombs), did not observe the Roman holidays, and denounced the gladiatorial shows.

2. Cannibalism, because the Christians referred to their holy communion as "the body and blood of Christ."

3. Atheism, because the Christians, like the Jews, worshiped no images.

4. Incest, because they openly spoke of their "love" for one another.

5. Disloyalty to the state. The Christians did not worship the emperor, and they preached about Jesus overthrowing the government of the world when he returned, which was expected to happen very soon. This charge caused the most trouble, because it brought the wrath of the emperors upon them. It is ironic that some of the best emperors, like the philosopher Marcus Aurelius (161-180), bitterly opposed the spread of Christianity because they saw it as a divisive movement.

A series of Christian writers, known as Apologists, refuted these false charges, and by showing that Christianity was superior to Judaism and paganism, they hoped to win the legalization of their faith. Justin Martyr's First Apology, which was written directly to the emperor Antoninus Pius, is an excellent example of this literature. He argued that Christians are really loyal citizens, who had been unfairly blamed for every bad thing that happened to the empire. These writers also produced writings called polemics, which refuted heresies such as Gnosticism which by then had crept into the Church. Some apologists worth remembering are Irenaeus (who challenged those who claimed that Jesus was not God and did not physically rise from the dead), Tertullian (who first used the term Trinity to explain God's nature), and Origen (who used allegory to bridge the gap between the Bible and classical Greek literature).

The personal behavior of Christians often gained converts. When a plague hit Alexandria, nearly everybody fled the city, but the Christians stayed behind to care for the sick and bury the dead. In a society where charity was rare, this made quite an impact. The personal bravery of Christians was also noticed. Even their enemies admitted that Christian courage in the face of death deserved praise. The sufferings of martyrs sometimes encouraged bystanders to declare themselves Christians, even though it meant almost certain death for them too.

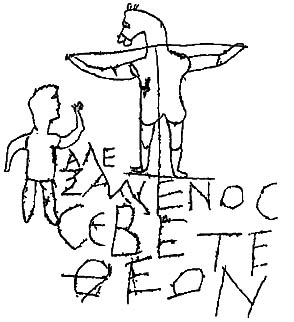

Archeologists sometimes find silent testimony to personal faithfulness. A crude piece of anti-Christian graffiti dating from about 225 A.D. was found on a Roman wall, depicting a boy raising one hand reverently to a crucified figure with the head of a donkey. Beneath it in Greek are mocking words: "Alexamenos worships his god."

Competitors to Christianity

As pointed out earlier, one of the reasons why people were willing to listen to the Christian message was because the Romans no longer fully believed in the gods of their ancestors. In place of the old polytheism some turned to Greek philosophy, especially Epicureanism, Stoicism, and Neo-Platonism. Others were attracted to the emotional experiences that Middle Eastern deities offered. From this perspective one could say that the Romans viewed Christianity as the latest Eastern cult to come their way, sort of like the way we view the Hare Krishnas and the Moonies.

The cult of Asia Minor's hundred-breasted fertility goddess, Cybele ("Diana of the Ephesians" in the book of Acts), was introduced to the Romans just before 200 B.C. She was permitted to stay because some thought she had driven away Hannibal, but many had misgivings about her. Cybele was worshiped in orgies where dancers went crazy and cut themselves with swords and knives. Her temple in Ephesus figured prominently in Paul's third missionary journey, and his subsequent letter to the Ephesians talked about spiritual warfare because he was writing to believers living in a city dominated by the occult.

Cybele was never as popular as her Egyptian counterpart, Isis, a more gracious and gentle deity. Romans, especially Roman women, were drawn to the 10-day initiation ceremonies of Isis, where the main event was a play that acted out the story of the death & rebirth of her husband, Osiris. This miraculous resurrection, supposedly achieved by the grief and faithfulness of Isis herself, was what made her cult appealing; her followers believed that their participation in the rites gained them immortality as well.

The Eastern religion that had the highest moral tone was a Persian import, Mithraism. The origins of Mithra (also called Mithras) go back to the Indo-European nomads of the second millennium B.C.; by the time the Romans met Mithra he had acquired Zoroastrian overtones and was portrayed with a halo of sunbeams, like the Greek Helios. Mithra was a champion of truth and light, whose followers joined him in fighting the powers of evil. It was a man's religion, with rigorous tests of initiation and a secret organization like modern Freemasonry. Its emphasis on fraternity and combat caused it to spread like wildfire when Roman soldiers discovered it; by the third century it was the army's unofficial religion. In a superficial way it resembled Christianity; for example, there was a ceremony similar to baptism, where bull's blood was used in place of water. But its overwhelming masculinity discouraged women from joining, whereas women played an important role in the Church. Its mystery nature also became a limiting factor; the Mithraists were so successful at keeping their doctrines secret from outsiders that no Mithraist literature exists today.

Persia also produced a prophet who attempted to bridge the gap between Zoroastrianism and Christianity. This was Mani (216?-276), who claimed he had God's final, universal revelation. Mani taught that there were two independent eternal principles, light and darkness, God and matter. Before the creation of the earth, light & darkness were separate; now they were intermingled; in the future they would be separated again. Jesus and all other religious leaders had been sent to release souls of light from the prison of their bodies. To Mani, all previous prophets--Moses, Buddha, Zoroaster and Jesus--had taught the truth, but their teachings had been corrupted in the centuries since. Therefore, it was Mani's job to straighten out their now-confused messages. To guard against similar corruption of his own work, Mani personally wrote his message down and prohibited careless copying of his texts. This backfired; Manichean scripture always remained scarce, and what we have now are scraps and paraphrases, mostly from religious rivals. By prohibiting mistakes, Mani effectively limited his followers to a few disciplined souls.

The Magi (Zoroastrian priests) did not care much for Mani's teachings, which implied that they had corrupted the teachings of their own prophet (Zoroaster). They had Mani imprisoned, and eventually executed, but the religion he founded took a lot longer to disappear. Manichean missionaries spread it to Africa, Europe, and even China. In 274 it was introduced to the Roman empire, and by the end of the century it had so many followers that the emperor Diocletian persecuted them, calling them Persian spies, even though they were also enemies of the Persian regime. St. Augustine was a Manichean at one point, but later refuted its teachings when he became a Christian. He and other Church leaders finally stemmed the tide, but Manicheism was not forced underground in the West until the sixth century. It was very popular in Mongolia in the 8th-9th centuries, and southern China saw a Manichean revival in the 13th-14th centuries.

Some of the Christian heresies may have gotten ideas from the Manicheans. The Paulician movement in the Byzantine Empire rejected Manicheism, but resembled it in its views on the struggle between light and darkness. The Paulicians in turn inspired the Manichean-like Albigensian heresy in southern France during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, provoking a crusade against them by Pope Innocent III. In the 14th century the last heirs of Manicheism were suppressed by the Ming emperors in China and the Inquisition in Europe.

The city of Dura-Europus, on the Syrian bank of the Euphrates, provides us with a view of how diverse religious life could be in the third century. On the frontier between East and West, it changed hands several times and acquired a mixed population of Greeks, Romans, Persians and Semites. Within its walls archeologists have found five Greek temples, a temple to Bel (a latter-day version of the Babylonian Marduk), a Christian chapel, a synagogue, a Mithraeum, and several shrines to pagan deities that were composites of Greco-Roman and Near Eastern gods. There was no fire-temple, but that might have been because the Persians destroyed the city around 260, just a generation after Zoroastrianism had been restored in its homeland.

The First Heresies

Besides the challenges from without, Christianity faced serious challenges from within. In Paul's first letter to the Corinthians, he criticized that church for splitting into factions centered on the personalities of human leaders, including himself. Not long after that on disagreements on matters of doctrine and practices arose, despite attempts to maintain unity. To an outside observer it must have looked like there were several Christianities, because these disagreements produced several factions, each with its own view of Christ and the scriptures, each claiming to be the Christianity.

One early split, the one that created the Ebionites, has already been discussed. Another split created Docetism, which taught that Jesus was a pure spirit-being who only appeared to be a man, uncontaminated by this imperfect world. There were many Docetists in Asia Minor near the end of the first century, prompting John to attack their views in his first and second epistles. Ignatius did the same in the early second century, writing that: "Jesus Christ was of the race of David, the child of Mary, who was truly born and ate and drank, was truly persecuted under Pontius Pilate, was truly crucified and died."

A second-century challenge came from Marcion, a wealthy ship-owner in Rome, who taught a deliberately anti-Jewish brand of Christianity and made his own list of authorized New Testament books. Around 172 a young Christian named Montanus proclaimed himself a prophet. His followers scorned the growing Church organization, which they saw as irrelevant since they expected the Lord to return very soon, and preached strict asceticism and fanaticism ("Do not hope to die in bed. . .but as martyrs.").

Similar attitudes were expressed in the third century when the question arose concerning what to do about Christians who renounced Jesus under threat of punishment. Many felt that those who wavered had committed the worst of sins, and would not forgive them. Led by a puritanical Italian clergyman named Novatian, these hardliners formed their own congregation in 251. They soon built up a network of Novatianist churches throughout the empire, calling themselves Cathari (pure ones) to distinguish themselves from the mainstream churches, which they considered polluted because of their lenient attitude toward sinners. Christians who became Novatianists had to be re-baptized, as if they were joining the only true church. Novatianists also refused to have communion with people who had been married more than once, and rejected the possibility of forgiveness for any major sin after baptism.

Novatianists were treated as heretics for a while in the fourth and fifth centuries, but they were really just fanatics, and by 600 they were reabsorbed into the mainstream churches. Novatianist clergymen were allowed to retain their rank when they rejoined the moderate majority.

The most dangerous fringe groups were a variety of religious movements that are collectively known to us as Gnosticism. Christian writers of the second century, especially Irenaeus, denounced Gnosticism as a perversion of Christianity. Gnostic beliefs varied considerably, but all were like the Manicheans in that they viewed the world as evil, created by an evil or ignorant God who was not the God of the New Testament. Sparks of divinity, however, are encased in the bodies of men, and when provided with secret knowledge (gnosis), they can be awakened and released to reunite with God.

The other Gnostic beliefs were even more bizarre. Most of them opposed sex and marriage; the creation of woman was evil because it allowed procreation, and every time a child was born one more soul fell into bondage under the powers of darkness. Some encouraged sinful behavior, claiming that the "knowledge" made them "pearls" that could not be stained by any mud from the world. Still others maintained that since matter is evil, Jesus must have been a spirit, not a real man (the Docetic view). The Cainites perversely honored Cain and the other villains of the Old Testament, while the Ophites venerated the serpent for bringing "knowledge" to Adam and Eve. Menander, who lived in Antioch late in the first century, claimed that whoever believed in him would not die; needless to say, his own death proved that he was a false prophet. His Ephesian contemporary, Cerinthus, taught that Jesus escaped from the cross and the Romans crucified someone else in His place, thinking it was Him. Irenaeus humorously tells us that the Apostle John fled from a bathhouse when he learned that Cerinthus was also there!

Remarkably, there is a surviving community of Gnostics today, the Mandaeans in Iraq and Iran. Three major texts are used by them: The Ginza, a detailed description of the Creation; the Johannesbuch, some late traditions about John the Baptist; and the Qolasta, a collection of prayers and liturgies. Most of these manuscripts were written between the 16th and 19th centuries, though individual excerpts may be older.

The Roman Response to Christianity

Like most pagans, the Romans were generally tolerant of other peoples' gods; after all, they might be Roman ones under different names! (e.g., Jupiter=Zeus=Ammon=Baal=Marduk) The only cults that were put on restriction were Christianity and the nature worship of the Druids. Druidism was off-limits because it practiced human sacrifice, and preferred Roman human sacrifice! Christianity was seen as having an attitude problem, because Christians denounced all other gods as demons from Hell.

At first the Romans had trouble telling the difference between Christians and Jews; in the first century they called Christians "Nazarenes" or "Jews who followed Chrestus" (Christ). As the practices of Christianity diverged from Judaism, this problem disappeared, but the Romans still did not know what to do with the unarmed revolutionaries that made up the Church; they certainly did not seem to deserve the special exemptions given to the Jews. Around 112, a perplexed Pliny the Younger, then governor of Bithynia and Pontus (two provinces in what is now northern Turkey), wrote to Emperor Trajan about the Christians living in his area. Full of misgivings about the government's standing order to execute them, Pliny wrote that instead of just killing accused Christians, he put them to a simple test: if they offered incense to a statue of the emperor and cursed Christ, they were allowed to go, because it was said that genuine Christians could not be persuaded to perform such acts. Trajan approved and added, "These people are not to be sought out. If they should be denounced and convicted, they must be punished, but with this proviso: anyone who denies he is a Christian . . . shall . . . obtain pardon through his recantation. Information published anonymously should never be admitted in evidence. That constitutes a very bad precedent and is not in keeping with the spirit of our times." For a century after that the official Roman response was what we would call a "don't ask, don't tell" policy: the government stopped looking for Christians, and only punished those who were accused and brought before the authorities.

The persecution of Christians before 250 was ugly enough but fortunately local in nature; while the authorities in one province threw them to the lions, others would leave them alone. The number of Christians grew steadily, until even the imperial household had some; Severus Alexander, the emperor from 222 to 235, is said to have kept a statue of Jesus in his private chapel, along with those of several emperors, Abraham, Orpheus, Apollonius of Tyana, Alexander the Great, and other great historical figures.

It was Decius (249-251) who first ordered an anti-Christian pogrom all across the empire. All citizens were commanded to sacrifice to the traditional Roman gods; those who did were given certificates proving that they obeyed the order. Many Christians complied to save their lives, while others escaped by bribing officials into giving them certificates without performing the sacrifices. Those who were unable (or unwilling) to obtain certificates were imprisoned and executed, including the bishops of Rome, Antioch and Jerusalem. But Decius was not emperor for long; he was killed in battle, and his successors were too busy with other problems to commit more than a few halfhearted persecutions, so the Christians were left in peace for forty years.

The persecutions did not cripple the Church; they strengthened it. Members who were not willing to support God's work 100 percent were weeded out in the process; those who were martyred were seen as receiving a special reward in Heaven. Tertullian dramatically stated that: "We multiply every time we are mowed down by you; the blood of Christians is seed." A fifth-century writer, Prudentius, transformed the stories of the early martyrs into a new body of legends. But he was occasionally carried away by his fervor: a tortured Christian utters six speeches against the heathens after his tongue has been cut out; and St. Lawrence, who was roasted on a grill, is made to say, "Turn me over; I'm done on this side." (see below)

The persecutions were the last gasp of pagan Rome; the final one, carried out by Diocletian, will be described in the next chapter. By the end of the third Christianity had won the empire; the last step in the process was the winning of the emperor.

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A History of Christianity

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|